Introduction

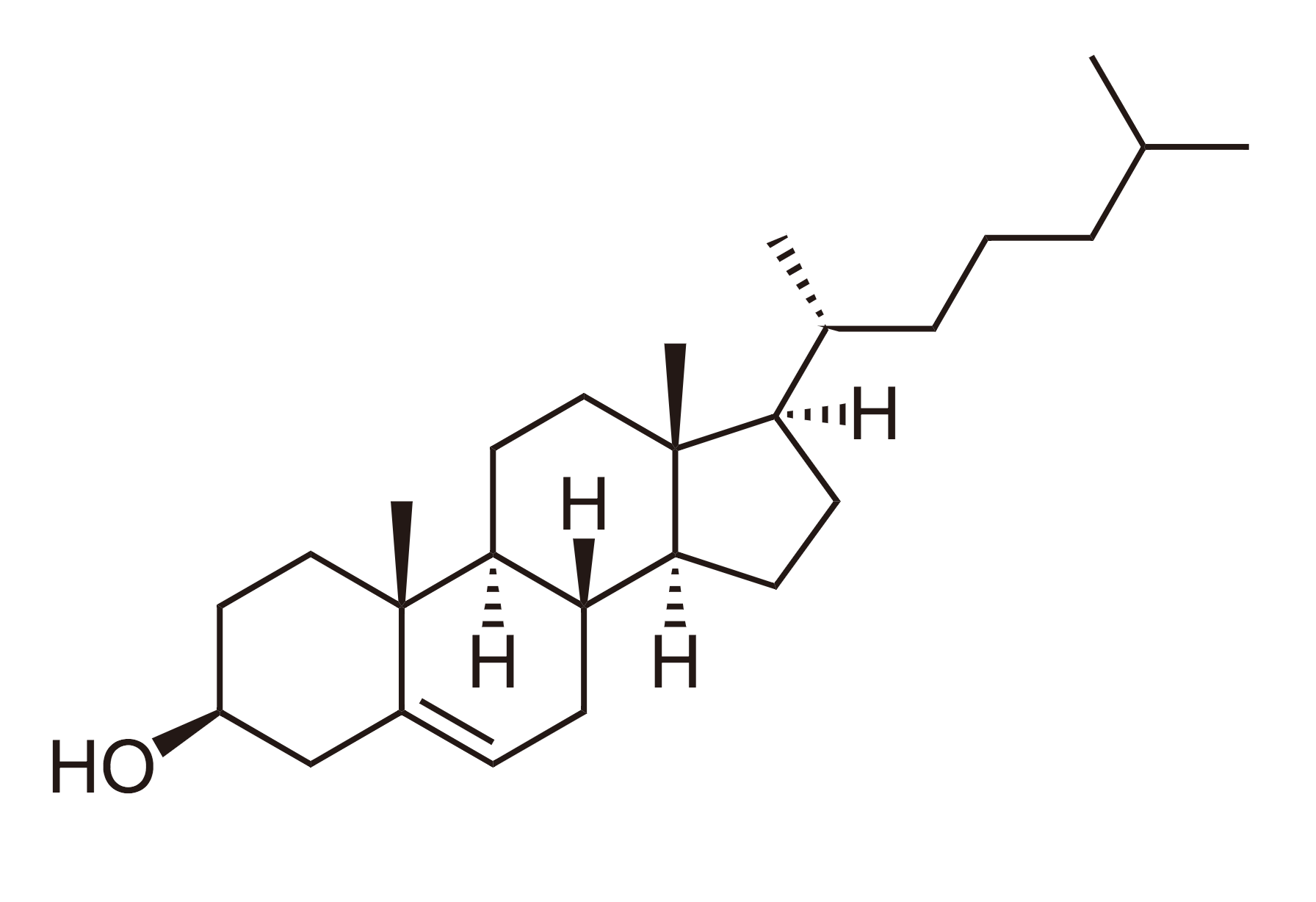

Cholesterol is a lipophilic molecule that is essential for human life. It has many roles that contribute to normally functioning cells. For example, cholesterol is an important component of the cell membrane. It contributes to the structural makeup of the membrane as well as modulates its fluidity. Cholesterol functions as a precursor molecule in the synthesis of vitamin D, steroid hormones (e.g., cortisol and aldosterone and adrenal androgens), and sex hormones (e.g., testosterone, estrogens, and progesterone). Cholesterol is also a constituent of bile salt used in digestion to facilitate absorption of fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K.[1]

Since cholesterol is mostly lipophilic, it is transported through the blood, along with triglycerides, inside lipoprotein particles (HDL, IDL, LDL, VLDL, and chylomicrons). These lipoproteins can be detected in the clinical setting to estimate the amount of cholesterol in the blood. Chylomicrons are not present in non-fasting plasma.

Issues of Concern

While cholesterol is central to many healthy cell functions, it also can harm the body if it is allowed to reach abnormal blood concentrations. Interestingly, when LDL-cholesterol levels are too high, the condition referred to as hypercholesterolemia, the risk for premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases (ASCVD) increases.[2] Particular care is necessary to educate patients about the harmful effects of high cholesterol and how to reduce their serum cholesterol levels. Patient lifestyle changes like diet (reduction in saturated fat and trans fat with an increase in fiber and total calories if obese and supplementation with plant stanols), smoking cessation, and exercise are often a favorable approach to cholesterol reduction. However, in cases that are refractory to these behavioral modifications, cholesterol-lowering drugs, such as statins, should be used.

Cellular Level

Cholesterol can be introduced into the blood through the digestion of dietary fat via chylomicrons. However, since cholesterol has an important role in cellular function, it can also be directly synthesized by each cell in the body. The synthesis of cholesterol begins from Acetyl-CoA and follows a series of complex reactions that will not be covered in this article. A primary location for this process is the liver, which accounts for most de-novo cholesterol synthesis.

Since cholesterol is mostly a lipophilic molecule, it does not dissolve well in the blood. For this reason, it is packaged in lipoproteins that have phospholipid and apolipoprotein.[3] Lipoproteins are made up of a lipid core (which can contain cholesterol esters and triglycerides) and a hydrophilic outer membrane comprising phospholipid, apolipoprotein, and free cholesterol. This allows the lipid molecules to move around the body through the blood and be transported to cells that need them. There are several types of lipoproteins that travel through the blood, and they each have different purposes. There are high-density lipoproteins (HDL), intermediate-density lipoproteins (IDL), low-density lipoproteins (LDL), and very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL). Notably, LDL particles are thought to act as a major transporter of cholesterol; at least two-thirds of circulating cholesterol resides in LDL to the peripheral tissues. Conversely, HDL molecules are thought to do the opposite. They take excess cholesterol and return it to the liver for excretion. Clinically, these two lipoproteins are significant since high LDL and low HDL increase patients' risk of atherosclerotic vascular diseases.[4][5]

Within the cell, cholesterol has several vital functions. Some of the primary uses for cholesterol are related to the cell membrane. It is required for the normal structure of the membrane; it contributes to its fluidity.[6] This fluidity can influence the ability of some small molecules to diffuse through the membrane, which ultimately changes the internal environment of the cell.[7] Also, within the membrane, cholesterol plays a role in intracellular transportation. Beyond its place in the cell membrane, cholesterol has several other biological functions. Of note, cholesterol is known to be an important precursor molecule for the synthesis of vitamin D, cortisol, aldosterone, progesterone, estrogen, testosterone, bile salts, among others.[8]

Related Testing

Physicians can order a lipid panel (lipid profile) to determine the cholesterol concentrations in a patient’s blood. A typical test result will include the concentrations of high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), triglycerides, and total cholesterol. These values are used to screen patients for abnormalities in cholesterol and triglyceride blood levels. With this information, physicians can estimate a patient's risk for certain health problems such as coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial disease (PAD), and stroke. Most laboratories report both LDL-cholesterol and non-HDL cholesterol, which is a secondary target for treatment.

Pathophysiology

Hypercholesterolemia (high LDL-cholesterol) is one of the major risk factors contributing to the formation of atherosclerotic plaques. These plaques lead to an increased possibility of various negative clinical outcomes, including, but not limited to, coronary artery disease. PAD, aortic aneurysms, and stroke. A major contributor to the increased risk of atherosclerotic lesion formation is high levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) in the blood. Also, it has been shown that an elevated high-density lipoprotein (HDL) blood concentration is correlated with a decreased risk in epidemiological studies, but clinical trials with therapies that elevate HDL-cholesterol have yielded null results. For this reason, a major focus of patient care is primarily to decrease LDL levels.

The process through which atherosclerotic plaques develop begins with endothelial damage. Endothelial damage leads to the dysfunction of endothelial cells, increasing the number of LDL particles that can permeate through the vascular wall. Lipoproteins, especially LDL, can then accumulate within the vessel wall trapped by the cellular matrix in the intima. LDL is then modified and taken up via scavenger receptors on macrophages resulting in foam-cell formation. As more lipid accumulates within the vessel wall, smooth muscle cells begin to migrate into the lesion. Ultimately, these smooth muscle cells encapsulate the newly formed plaque forming the fibrous plaque, the protector of the lesion, preventing the lipid core from being exposed to the lumen of the vessel. Atherosclerotic plaques can lead to occlusion of the vessel (decreasing blood flow distally and causing ischemia) or, more commonly because of abundant lipid and macrophages (vulnerable plaque) rupture, inducing the formation of a thrombus which can completely block the flow of blood (as occurs in acute myocardial infarctions, unstable angina).

Clinical Significance

Hypercholesterolemia refers to the condition in which a patient has elevated blood concentrations of LDL-cholesterol. High LDL is of particular clinical importance, but it should be noted that hypercholesterolemia can also include very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) and intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL), i.e., non-HDL-cholesterol. High LDL levels have been associated with an increased risk of atherosclerosis, potentially leading to several other conditions such as coronary artery disease, stroke, and peripheral arterial disease. Several factors can lead to increased LDL levels. Some of these factors include genetics, diet, stress, sedentary lifestyle, medications, and other disorders such as nephrotic syndrome and hypothyroidism.

On clinical examination, looking for absent pulses, bruits, arcus senilis (younger than 50 years of age), tendon xanthoma, xanthelasma, and aortic stenosis are all stigmata of very high cholesterol levels as in familial hypercholesterolemia.

Genetic defects that lead to increased LDL levels in the blood include genes that regulate LDL receptors in the liver. LDL receptors mediate the uptake of LDL into the liver. Endocytosis of LDL is the primary way that the body decreases cholesterol levels, so it follows that a decrease in LDL receptor function would also increase LDL concentrations in the blood. Patients with a genetic disposition for high cholesterol can be placed on cholesterol-lowering medications like statins to decrease their risk.

Diet has a variable effect on cholesterol levels among individuals.[9] However, it has been shown that diets high in saturated fats and trans fats can increase cholesterol in the blood.[10] Dietary cholesterol has not been shown to contribute significantly to LDL concentrations, but its role is still in question.[11][12][13] Lifestyle changes such as regular aerobic exercise can also help control cholesterol levels. Saturated fats should not comprise any more than 7% to 10% of the diet.

Hypercholesterolemia is often treated medically with lifestyle modification and medications. The goal of lifestyle changes is typically for the patient to increase physical activity, lose weight, and follow a heart-healthy diet. For patients with higher risk, a lipid-lowering drug (often a statin) will be used in conjunction with these behavioral changes. Statins have been shown to reduce ASCVD in patients and are the favored drugs because there are now generic formulations that make them cost-effective.[14][15][16][17]