Continuing Education Activity

Understanding opioid equivalency is essential to effectively managing cancer-related and chronic pain. Tailored for healthcare providers involved in pain management, the activity emphasizes the significance of comprehending and applying opioid equivalent dosing, especially for opioid-tolerant patients needing opioid rotation. Participants will explore the methods and principles of equianalgesic conversion between different opioids, aiding in therapeutic transitions while optimizing analgesic effectiveness and mitigating potential adverse effects.

This activity for healthcare professionals highlights insights into the nuances of opioid equivalency calculations, enabling more informed decisions when transitioning patients between opioid therapies. Emphasis is placed on the interprofessional collaboration required to establish appropriate opioid rotations, ensuring patient safety and pain relief. Participants refine their skills in selecting suitable opioid doses while maintaining patient-centered care. This activity aims to empower clinicians with the knowledge and tools necessary to navigate opioid rotation strategies effectively and includes case examples to illustrate opioid equivalency concepts, thereby improving pain management outcomes for patients with cancer-related or chronic pain.

Objectives:

Identify patient-specific factors influencing opioid tolerance and response to inform equianalgesic dose calculations and opioid rotation decisions.versions.

Differentiate between various opioid analgesics and their equianalgesic dosing profiles to ensure appropriate selection based on patient needs and clinical context. therapies.

Implement standardized protocols for equianalgesic dose calculations and opioid rotation strategies, considering individual patient characteristics and safety concerns, to optimize pain management outcomes.

Collaborate with interdisciplinary teams to integrate diverse perspectives and expertise in equianalgesic dose calculations and opioid rotation strategies.

Indications

Opioid drugs are commonly used as analgesics for chronic pain. These drugs are generally reserved for moderate or severe pain because of the risk of dependence, withdrawal, and opioid use disorder (OUD) they carry. However, opioid drugs may be prescribed for mild to moderate pain that is not alleviated with non-opioid analgesics.[1][2] Some opioid drugs, including buprenorphine and methadone, can be used for both pain and OUD.

Many opioid drugs, in a variety of formulations, are utilized in the treatment of chronic pain. Codeine and tramadol are used for mild to moderate chronic pain that is not alleviated by non-opioid analgesics. These drugs are available as oral formulations. Morphine, oxycodone, hydromorphone, and oxymorphone are used for moderate to severe chronic pain. Oxycodone and oxymorphone are available exclusively as oral formulations, whereas morphine and hydromorphone are available as both oral and parenteral formulations. Fentanyl is typically reserved for severe chronic pain. It has poor oral bioavailability and is therefore formulated for parenteral administration. Buprenorphine and methadone are most commonly used in chronic pain for patients with OUD. Buprenorphine has poor oral bioavailability and is formulated for parenteral administration. Oral methadone is most often utilized for chronic pain.[2]

Mechanism of Action

The majority of opioid analgesics used in chronic pain are full mu-opioid receptor agonists. Examples include morphine, hydromorphone, fentanyl, oxycodone, hydrocodone, and methadone. Buprenorphine is a partial mu-opioid receptor agonist that produces a reduced analgesic effect as compared to full mu-opioid receptor agonists.[2] However, because they act on a common receptor, these drugs are interchangeable, provided their doses are adjusted for relative analgesic potency.[3]

Administration

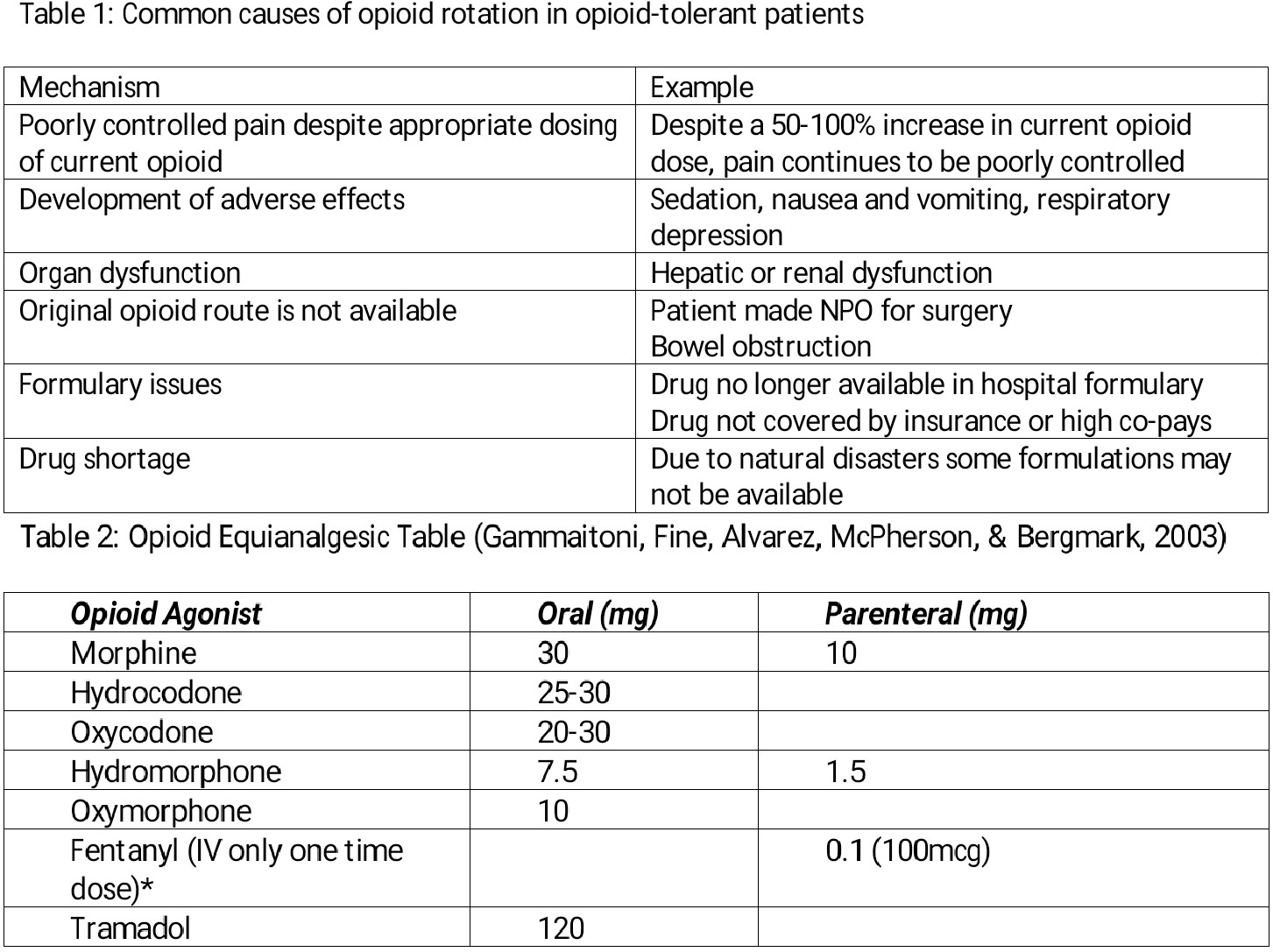

The term equianalgesia, meaning “approximately equal analgesia,” refers to the doses of various opioid analgesics that are estimated to provide the same amount of pain relief. Equianalgesic dose calculations are a means for selecting the appropriate initial dosing when changing from one opioid agent or route of administration to another. An equianalgesic chart provides a list of analgesic doses, both oral and parenteral, which approximate each other in their ability to provide pain relief (ie, equianalgesic units). The equianalgesic chart (Table 2) lists estimates for equianalgesic doses; individual patients may require different doses based on a variety of factors, including level of opioid tolerance and organ function. Equianalgesic calculations occur in Oral Morphine Equivalents (OME).

Most patients on chronic opioids develop tolerance to the analgesic and non-analgesic effects of opioids, such that a previously effective dose gradually loses efficacy. This usually manifests as a shortened action duration and often requires dose escalation to maintain adequate analgesia. Cross-tolerance is the development of tolerance to the effects of pharmacologically related drugs, particularly those that act on the same receptor site. However, when switching to another opioid, clinicians need to assume that cross-tolerance is incomplete, which means that the starting dose of the new opioid must be reduced by at least 50% of the calculated equianalgesic dose to prevent overdose and related sequelae.[4]

Equianalgesic Opioid Dose Calculation and Conversion Steps

- Determine the total daily dose of the current opioid

- Calculate the 24-hour OME:

- Add up all the scheduled and breakthrough opioid doses in 24 hours. Using the equianalgesic dose chart, determine the 24-hour OME of the current opioid. (24-hour OME = (24-hour dose of current opioid x [30 /Number of equianalgesic units for the current opioid])

- Select the new opioid and route of administration. Using the equianalgesic dose chart, determine the 24-hour dosage of the new opioid. (24-hour dose of new opioid = (24-hour OME x [Equianalgesic units of new opioid / 30])

- Decrease the dose of the new opioid to account for incomplete cross-tolerance. Multiply the dose of the new opioid by 0.5 (50%) to obtain the final 24-hour dose of the new opioid. If you are only converting an opioid's route of administration (ie, you are using the same opioid by a new route), this calculation is not required.

- Develop a pain prescription, considering the half-life of the new opioid.

Example 1:

BT is a patient with lung cancer and painful bony metastases who takes extended-release morphine 90 mg by mouth every twelve hours. They are admitted to the hospital for a planned procedure to stabilize lytic bony metastases. They are not to take oral medications (NPO) before surgery. The patient is likely to experience uncontrolled pain if they are unable to take morphine.

- Determine the total daily dose of the current opioid: morphine 90 mg by mouth every 12 hours (90 mg + 90 mg = 180 mg)

- Calculate the 24-hour OME: (180 mg morphine x [30/30]) = 180 mg OME

- Select the new opioid and route of administration: The patient is NPO for surgery, and their oral morphine requirement is replaceable by a continuous infusion of morphine (24-hour dose of the new opioid = (180 mg X [10 / 30]) = 60 mg).

- Decrease the dose of the new opioid to account for incomplete cross-tolerance: Since morphine remains the drug to be used for the patient's pain, this calculation is not required.

- Develop a pain prescription, considering the half-life of the new opioid: A continuous intravenous (IV) infusion of morphine would run at 2.5 mg/h (60 mg/ 24 hours = 2.5 mg/h). In clinical practice, IV infusion of opioids may be optimized to deliver additional medication during episodes of breakthrough pain. This is called patient-controlled analgesia. Thus, the prescription could also be modified to include a basal continuous IV infusion of 2 mg per hour and a bolus dose of 0.5 mg every 30 minutes as needed for breakthrough pain.

Example 2:

During their hospital stay, BT develops acute renal insufficiency following the stabilization procedure. To avoid toxicity from morphine due to poor renal clearance of active metabolites, the decision is made to switch the patient to IV hydromorphone. Of note, the patient's pain was well-controlled with a continuous IV infusion of morphine at 2.5 mg/h.

- Determine the total daily dose of the current opioid: Morphine 2.5 mg/h IV (2.5 mg/h x 24 hours = 60 mg)

- Calculate the 24-hour OME: (60 mg morphine x [30 / 10]) = 180 mg OME

- Select the new opioid and route of administration: IV hydromorphone lacks clinically relevant metabolites that require renal clearance and is considered safe for patients with renal insufficiency (24-hour dose of new opioid = (180 x [1.5 / 30]) = 9 mg

- Decrease the dose of the new opioid due to incomplete cross-tolerance: While the patient is tolerant to morphine, their tolerance to hydromorphone is likely incomplete. Their hydromorphone dose will need to be decreased by 50% (9 mg x 0.5 = 4.5 mg).

- Develop a pain prescription, considering the half-life of the new opioid: A continuous IV infusion of hydromorphone would run at 0.2 mg/h (4.5 mg/ 24 hours = 0.1875 mg/h, rounded to 0.2 mg/h).

Case Example 3:

Approaching discharge from the hospital, BT reports that their pain has been controlled with IV hydromorphone. However, her renal function has not recovered. Thus, to facilitate a safe transition of care, BT needs to be switched to oral opioids that are safe to use in renal dysfunction.

- Determine the total daily dose of the current opioid: Hydromorphone 0.2 mg/h IV (0.2 mg/h x 24 hours = 4.8 mg

- Calculate the 24-hour OME: (4.8 mg hydromorphone x [30 / 1.5]) = 96 mg OME

- Select the new opioid and route of administration: Hydromorphone is available in both 24-hour and short-acting oral formulations (24-hour dose of new opioid = (96 X [7.5 / 30]) = 24 mg).

- Decrease the dose of the new opioid to account for incomplete cross-tolerance: Since hydromorphone remains the drug to be used for the patient's pain, this calculation is not required.

- Develop a pain prescription, considering the half-life of the new opioid: BT has required around-the-clock pain control prior to and during admission. Thus, providing a basal dose of hydromorphone is advisable. Fifty percent of the new, daily opioid dose is 12 mg (24 mg x 0.5 = 12 mg) and comprises a sufficient basal dose. The rest of the daily opioid dose (12 mg) may be given for breakthrough pain. Therefore, a prescription for hydromorphone ER 12 mg by mouth daily and hydromorphone IR 2 mg by mouth every 4 hours as needed for breakthrough pain is optimal for BT.

Adverse Effects

Adverse effects are common during opioid therapy. In particular, patients on opioids should be monitored for constipation, nausea, vomiting, sedation, impaired psychomotor function, and urinary retention. Among gastrointestinal adverse effects, opioid-induced constipation (OIC) affects between 45% and 90% of patients and is a source of significant morbidity.[5] This adverse event is the most prevalent reason patients avoid or discontinue opioids and can often result in an increased length of hospital stay and overall healthcare costs.[6][5][7][8][9][10] Nausea is seen most commonly at the start of therapy. However, patients commonly develop tolerance to the emetic effects so within 3-7 days.

Opioids may also exhibit neuroexcitatory effects that might not be easily recognized. Myoclonus is typically a herald symptom. Myoclonus, which is the uncontrollable jerking and twitching of muscles/muscle groups, most frequently occurs in the extremities. Higher opioid doses may cause myoclonus more frequently, but the dose relationship is variable.[11] As myoclonus worsens, patients may develop other neuroexcitatory signs, including hyperalgesia (increased sensitivity to noxious stimuli), delirium with hallucinations, and grand mal seizures. Treatment of neuroexcitatory effects involves decreasing the opioid dose, opioid rotation, or the addition of a benzodiazepine.

Sedation occurs in 20% to 60% of patients on opioids and occurs most commonly when patients initiate opioid therapy or receive a higher dose.[4] Mild-to-moderate sedation typically abates in a few days. Moderate-to-severe sedation usually responds to opioid dose reduction but may also necessitate opioid rotation.

Both pruritus and urinary retention are rare adverse effects of opioid use. A combination of topical agents and/or systemic, low-dose opioid antagonists are commonly used to treat pruritus. Acute urinary retention needs urgent medical attention; if it is related to the opioid, either the opioid dose can be reduced or the opioid can be discontinued.

Monitoring

All patients on chronic opioid therapy regimens require monitoring for the efficacy and safety of treatment. Monitoring includes regular pain assessments that investigate pain levels, changes in the quality of pain, and pain recurrence. Additionally, patients should be screened for adverse effects from analgesics, including somnolence, constipation, and nausea. Liver and kidney function should also be monitored regularly as impaired function can alter opioid metabolism and excretion.

Toxicity

Naloxone, a semisynthetic opioid antagonist, is indicated for the reversal of life-threatening respiratory depression induced by opioids. Depending on the dose, naloxone administration to a physically dependent patient on opioids will cause an abrupt return of pain and can precipitate withdrawal syndrome, with symptoms ranging from mild anxiety, irritability, and muscle aches to life-threatening tachycardia and hypertension.[12] Newer peripherally acting opioid antagonists, such as methylnaltrexone and naloxegol, antagonize peripheral mu-opioid receptors and are used to treat refractory OIC.[13]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Optimal patient analgesia is best accomplished through the efforts of an interprofessional healthcare team that includes clinicians, specialists, nursing staff, and pharmacists. When these team members are involved with patients in scenarios such as the above cases, they must be well-familiarized with opioid equivalency and monitoring patient pain control. This responsibility falls to the prescribing or ordering clinician and should be double-checked by the pharmacist. If a nurse is administering or counseling the patient on how to take the medication, they should also be trained on opioid equivalence and equianalgesia. This interprofessional approach will minimize opioid misuse and dependence, prevent adverse events, and provide the patient with the needed analgesia for their situation.