Continuing Education Activity

Chiggers are the larvae of the Trombiculidae mite species. Bites from these mite larvae can cause local pruritus and irritation called trombiculiasis or trombiculosis. The reaction is usually mild and self-limited, but the bites can transmit disease or result in bacterial superinfection. While there are many species of parasitic mites in a variety of habitats worldwide, the species most commonly referred to as chiggers include Eutrombicula alfreddugesi in the south of the United States, Trombicula autumnalis in Europe, and the Leptotrombidium genus in Asia-Pacific.

The larvae of these species feed on the skin of various animals, including humans. An inflammatory reaction with surrounding erythema, a variable degree of swelling, and intense pruritus occurs. The larvae easily dislodge by scratching and rarely remain attached to humans for more than 48 hours, but the intense pruritus, inflammation, and localized allergic response may last for weeks. Typically, the diagnosis of trombiculiasis is based on a history of exposure to a trombiculid habitat, the characteristic lesion pattern, and the exclusion of other possible diagnoses. The management of chigger bites is focused on symptom control with oral antihistamines or topical corticosteroid creams. This activity for healthcare professionals aims to enhance learners' competence in diagnosing chigger bites, symptomatic management, implementing preventive strategies, and fostering effective interprofessional teamwork to improve outcomes.

Objectives:

Identify characteristic signs of chigger bites, distinguishing them from other dermatological conditions.

Implement evidence-based interventions promptly for chigger bite management, considering severity and patient-specific factors.

Apply appropriate preventive measures, educating patients on avoiding chigger-infested areas and protective clothing

Collaborate with interprofessional team members to educate patients regarding chigger bite prevention and pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for optimal patient outcomes.

Introduction

Chigger is the common name for species of the Trombiculid family of mites. Bites from the larva of these mites can cause local pruritus and irritation. This is called trombiculiasis or trombiculosis. The reaction is usually mild and self-limited, but the bites may rarely transmit disease or result in a bacterial superinfection.[1] While there are many species of parasitic mites in a variety of habitats worldwide, the species most commonly referred to as chiggers include Eutrombicula alfreddugesi in the south of the United States, Trombicula autumnalis in Europe, and the Leptotrombidium genus in Asia-Pacific.[2][3]

The larvae of these species feed on the skin of various animals, including humans. Adult mites burrow into the soil and feed on detritus, while the larvae of these species accumulate on the edges of leaves and grass before hitching onto a passing host. They then migrate to a preferred feeding site, attach themselves to the host’s skin, and secrete proteolytic enzymes to digest host epidermal cells.[4] This provokes an inflammatory reaction with surrounding erythema, a variable degree of swelling, and intense pruritus. The larvae easily dislodge by scratching and rarely remain attached to humans for more than 48 hours, but the intense pruritus, inflammation, and localized allergic response may last for weeks. Seldom, the light-red to orange-colored larva, measuring 0.15 to 0.3 mm in length, may be identified on the skin. More typically, the diagnosis of trombiculiasis is based on a history of exposure to a trombiculid habitat, the characteristic lesion pattern, and the exclusion of other possible diagnoses.[1] The management of chigger bites is focused on symptom control with oral antihistamines or topical corticosteroid creams.

Etiology

Trombiculiasis, by definition, is caused by the bite of trombiculid mites and requires exposure to these larval mites' preferred habitat. Once bitten, digestive enzymes secreted by the mite cause liquefaction of the host's epidermis, leading to a localized hypersensitivity reaction characterized by papules, erythema, and urticaria.[1][5]

Epidemiology

Larval mites mature to their parasitic stage between June and September in the Northern Hemisphere. Therefore, nearly all instances of trombiculiasis occur in the summer and fall. In tropical areas worldwide, however, exposure may occur at any time of the year.[1] Chigger bites can occur in patients of any age with a history of exposure to chigger habitats. These habitats include overgrown fields, wooded areas, or ground with moist soil near bodies of water. Trombiculiasis has traditionally been associated with occupational exposure among harvest workers but can also occur in suburban or urban areas with exposure to grassy fields and overgrown lawns or gardens. Therefore, the true incidence of trombiculiasis is largely unknown and limited to case reports due to the self-limited nature of the disease, which frequently leads to underreporting.[6]

Chiggers are known vectors of scrub typhus in humans.[7] Scrub typhus is caused by the bacteria Orientia tsutsugamushi. The risk of disease in humans in urban areas is not well established; however, a recent study from Thailand reported a high prevalence of chigger infestation in 76.8% of animals trapped in urban public parks from Bangkok.[7] O tsutsugamushi was not detected in their study. Chigger-associated scrub typhus has a broad geographical distribution, though previously, this condition was thought to occur only in the Asian-Pacific area and northern Australia, with the area being identified as the "Tsutsugamushi Triangle."[8] However, reports of scrub typhus in Africa, southern Chile, and the Middle East have broadened the endemic area of this disease. A recent study reported evidence of Rickettsia infections from US chiggers found in North Carolina.[8]

Pathophysiology

Trombiculid mites gain access to human skin via direct contact through pant cuffs, open sleeves, or shirt collars. The larvae then migrate on the skin. Barriers to this migration (eg, a belt or elastic waistband) cause the clustering of larvae in these areas.[9] Once attached to the skin, the larvae secrete digestive enzymes to liquefy epidermal cells for feeding, inducing local irritation and inflammation at the bite site.

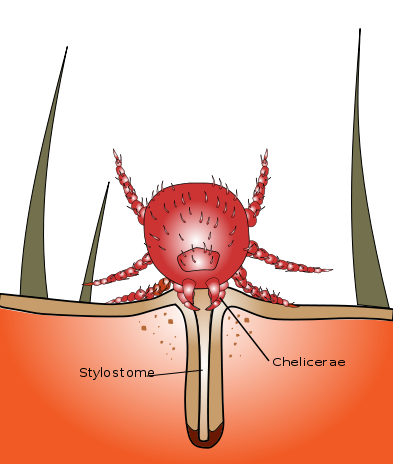

As the larval mite liquefies epidermal cells, the skin around the bite will become edematous. This forms a papule around the mite, leading to the impression that the mite has burrowed into the skin. (see Image. Chigger Stylostome). The mite can sometimes be seen on or within the papule but will usually have become dislodged before the irritation begins. The pruritus usually resolves within a few days but may last as long as 2 weeks. Chigger bites progress into erythematous papules that may appear as clusters. Surrounding macules, vesicles, and rarely, bullae may also develop. Because the mites migrate on the host's body to a protected area with thin skin, they often accumulate along the borders of tightly fitting clothing. Several bites in a linear pattern may occur along the waistband, the in-seam of underwear, or above socks or shoes.[5]

History and Physical

Trombiculosis

Chigger bites can occur in any person exposed to the appropriate habitat during the summer months. Patients with occupational exposure will probably be familiar with chigger bites, but even working in a suburban yard, garden, or a casual walk in the park may expose a patient to trombiculid mites. Cutaneous inflammation and intense pruritus followed by a papular and papulovesicular cutaneous rash are typical of trombiculosis.[1] A typical patient will present after a few days of intense itching with grouped or linear patterns of papules on exposed skin or along a line next to tight-fitting clothes. The papules may develop surrounding dark red to violaceous macules or into vesicles typically located around the legs and waistline. Rarely, bullae may form.[2] Pruritis usually resolves within a few days. Prolonged cutaneous eruption with pruritus is rare but can occur.[1] (see Image. Chigger Bites and Healing Chigger Bite)

Summer Penile Syndrome

Penile swelling, pruritus, and dysuria can occur in young boys due to a local hypersensitivity response to chigger bites on the penis.[10] This tends to be a seasonal phenomenon and is hence described as "the summer penile syndrome" or lion's mane penis.[5] Affected patients usually range in age from 7 months to 11 years. Pruritis is the most common symptom, reported in up to 84% of the patients in one study. Penile edema, a papule or bite puncture mark, and erythema are frequently noted. Symptom duration is typically approximately 4 days but may range from 1 to 18 days.[10] Itching usually resolves without intervention after 2 to 3 days but can last as long as 2 weeks.[2]

Scrub Typhus

Chiggers are known vectors of scrub typhus, which is a bacterial infection caused by a gram-negative coccobacillus, O tsutsugamushi.[11] Although Hantavirus,[12] Borrelia burgdorferi,[13] and Ehrlichia phagocytophila[14] have been detected in trombiculid mites, the transmission of these diseases from trombiculid mites to humans has not been reported.

Scrub typhus presents with headache, anorexia, and malaise, usually slow onset.[15] Some patients may have an abrupt onset of high fever, intense headache, and diffuse myalgias.[15] A centrifugal maculopapular rash is seen in 50% of the patients, which usually begins on the abdomen and then spreads to involve the extremities and the face. Petechiae formation is rare. In contrast to the rash associated with chigger bites, this rash is nonpruritic. At the site of the chigger bite, however, an eschar with central necrosis will be seen.[16] Other signs and symptoms of scrub typhus include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, generalized lymphadenopathy, and relative bradycardia.[17] In elderly patients, acute kidney injury with altered sensorium is more prevalent than in younger patients infected with scrub typhus.[18] A recent case report identified QT prolongation with focal ischemic changes on an electrocardiogram (ECG) of a patient with afebrile scrub typhus and a normal coronary angiogram.[19] The patient's ECG changes resolved after treatment with doxycycline.

Evaluation

Chigger bites are clinically diagnosed; therefore, no diagnostic studies are necessary. A history of outdoor exposure during the summer or early fall, along with a characteristic pattern of scattered urticarial papules, establishes trombiculiasis as the presumed diagnosis.[1] (see Image. Chigger Bite Eschar) Similarly, no laboratory test reliably identifies scrub typhus in the infection's early phase. Clinical assessment is the key to the diagnosis of this infection. When suspected, serologic testing can be used to confirm the diagnosis. A 4-fold increase in titers drawn at least 2 weeks apart using an indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) confirms the diagnosis of acute scrub typhus.[20] Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays for scrub typhus have been developed but are not widely available.

Treatment / Management

The management of chigger bites is supportive, focused on symptom control with oral antihistamines or topical corticosteroid creams. Cold compresses may also help decrease discomfort and localized swelling. Suffocating the parasite by covering the bite in nail polish, vaseline, or cream is not recommended.[1][5]

Itching can be treated with topical menthol or calamine lotion. Severe cases may be treated with potent topical corticosteroids and occlusion.[5] Intralesional corticosteroid injections of triamcinolone acetonide can be used for patients without improvement with topical therapy.[21] In the vast majority of cases, however, this is unnecessary. Exposed clothing should be washed in hot water or treated with insecticides to kill the larvae.[22]

Scrub typhus is typically treated with doxycycline. Literature reviews suggest that azithromycin, rifampin, and chloramphenicol may also be effective treatments.[23] However, azithromycin specifically should be used in pregnant patients due to contraindications to other antibiotics in pregnancy. Combination therapy may be necessary for patients with severe disease.[24]

Differential Diagnosis

The appearance of scattered papules along exposed skin or clustered around tightly fitted clothing after an outdoor exposure naturally suggests arthropod bites. Among the differential diagnoses, clinicians should consider scabies, bedbug bites, and exposure to mosquitoes or ants. Flea bites may sometimes be in a linear pattern along tightly fitting clothing and should be considered in patients with indoor animals.

Rashes from many other infectious agents, autoimmune conditions, or sensitivity reactions may have a similar appearance. The history of outdoor exposure, the seasonal nature of symptoms, and the absence of recurrence are important to distinguish trombiculiasis from other causes of rash. Trombiculiasis should not be the presumed diagnosis in any patient who appears ill, has abnormal vital signs, has extensive vesicles or bullae, or whose lesions are painful instead of pruritic.[1][5]

Summer penile syndrome, as a particular and localized form of trombiculiasis, has its differential diagnosis, including balanitis, phimosis, and paraphimosis. Balanitis is a painful inflammation of the glans penis, which may be associated with purulent exudate and erosion of the skin covering the glans. Phimosis is a constriction of the foreskin, preventing it from fully retracting over the glans. Paraphimosis is a constriction of the foreskin in which the foreskin is stuck over the glans or shaft of the penis, restricting circulation to the glans. Both conditions may also be associated with penile swelling. In summer penile syndrome, the edematous skin should be minimally tender and retract easily over the glans in uncircumcised males. Cellulitis and abscesses must be excluded as well.[10]

Prognosis

Usually, trombiculiasis resolves spontaneously within a few weeks without repeated exposure. The risk of superimposed bacterial infection or bacterial disease transmission is generally quite low. Therefore, the prognosis of chigger bites is usually good. If there is reinfection potential, the patient should be counseled to avoid chigger habitats, cover the skin when passing through infested areas, and use repellents and insecticides to avoid exposure.[1][5]

Complications

Complications from trombiculiasis include cellulitis from excoriations, summer penile syndrome, and the transmission of scrub typhus. Untreated scrub typhus can result in severe disease with multiorgan failure and death.[25] Other systemic manifestations of scrub typhus include arrhythmias, ischemic changes, and QT prolongation.[19]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Prevention is the key to limiting chigger bite-associated illnesses. Avoiding areas of chigger infestation is the easiest way to prevent trombiculiasis. If exposure is unavoidable, patients should be advised to use elastic bands to close the hems of sleeves and pant legs tightly against the skin, to cover the skin completely, or to tuck the hems of their pants into socks or boots. DEET repellent and permethrin are also effective deterrents to chigger bites.[1][5] Insect repellents are highly effective in repelling these mites and should be used when exposure is a possibility.[26]

N,N-diethyl-3-methylbenzamide

N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide or N,N-diethyl-3-methylbenzamide (DEET) repellent is highly effective against these larvae and is considered the gold standard treatment for prevention.[27] DEET has been regarded as the most efficacious insect repellent for the last 6 decades and has a strong safety record with excellent protection against ticks, mosquitoes, and other arthropods.[27] Although DEET is available in many different formulations, its effectiveness plateaus at approximately 30% concentration.[28] However, a higher percentage formulation is expected to provide a longer duration of protection.[27] Serious adverse effects are uncommon. Excessive exposure through the skin has been associated with dermatitis and allergic reactions. In rare cases, neurotoxicity with seizures may occur.[29] DEET is safe to use in children older than 2 months of age, but caution is needed to ensure accidental oropharynx exposure and ingestion do not occur.

Permethrin

Permethrin is a synthetic compound neurotoxic to insects but does not cause systemic toxicity in humans.[22] This compound is applied to clothing and bedding and is effective against ticks and chiggers. Permethrin-treated clothing maintains its efficacy through multiple wash cycles; however, permethrin's repellency is significantly inferior compared to 50% DEET spray.[30]

Pearls and Other Issues

Key facts to bear in mind regarding chigger bites include the following:

- Chigger bites typically occur during summer and early fall in those with recent outdoor exposure. However, in tropical areas of the world, chigger bites can occur year-round.

- Patients usually display pruritic papules, sometimes clustered around tightly fitting clothes.

- Itching usually lasts a few days but can sometimes extend as long as 2 weeks.

- Lesions can sometimes form vesicles or bullae and may have surrounding violaceous macules.

- Treatment is usually restricted to oral antihistamines, cold compresses, and topical corticosteroids.

- Prevention of recurrent exposure can be achieved by completely covering the skin or using insect repellents such as DEET and permethrin.

- Notable complications of chigger bites include secondary cellulitis, summer penile syndrome, and transmission of other diseases such as scrub typhus.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Trombiculiasis is easy to diagnose in the right clinical scenario. Chigger bites have an excellent prognosis, and supportive management is all that is typically required. However, given the potential for transmission of serious infections through chigger bites, future exposures should be prevented, which requires an interprofessional team approach to care. Patients and caregivers should be educated regarding appropriate clothing and the use of insect repellents to avoid these bites. The clinical nurse is essential in providing this education as a primary or secondary preventive measure. Occupational nurses are pivotal in ensuring workers exposed to chigger-infested environments are adequately protected.

Clinicians should ensure there are no signs of chigger-borne infections when a patient presents for the evaluation of a chigger bite. Pharmacists can counsel patients on symptomatic treatment options and consult with the clinician if needed. All care team members should maintain accurate, updated medical records and communicate with other caregivers if necessary. A well-integrated interprofessional team of clinicians and nurses can decrease the incidence of chigger bites and their associated infections.