Introduction

The deep cervical fasciae of the neck, since its first description in the early 1800s, have been a source of considerable controversy amongst anatomists. Several different classification systems for these anatomic structures have been proposed based on topographic morphology, embryologic origin, and surgical approach. The most commonly accepted classification system found in the literature is by topographic morphology (i.e., basic anatomy), however considerable variation in the nomenclature and anatomic description of these facial layers exist.[1][2]

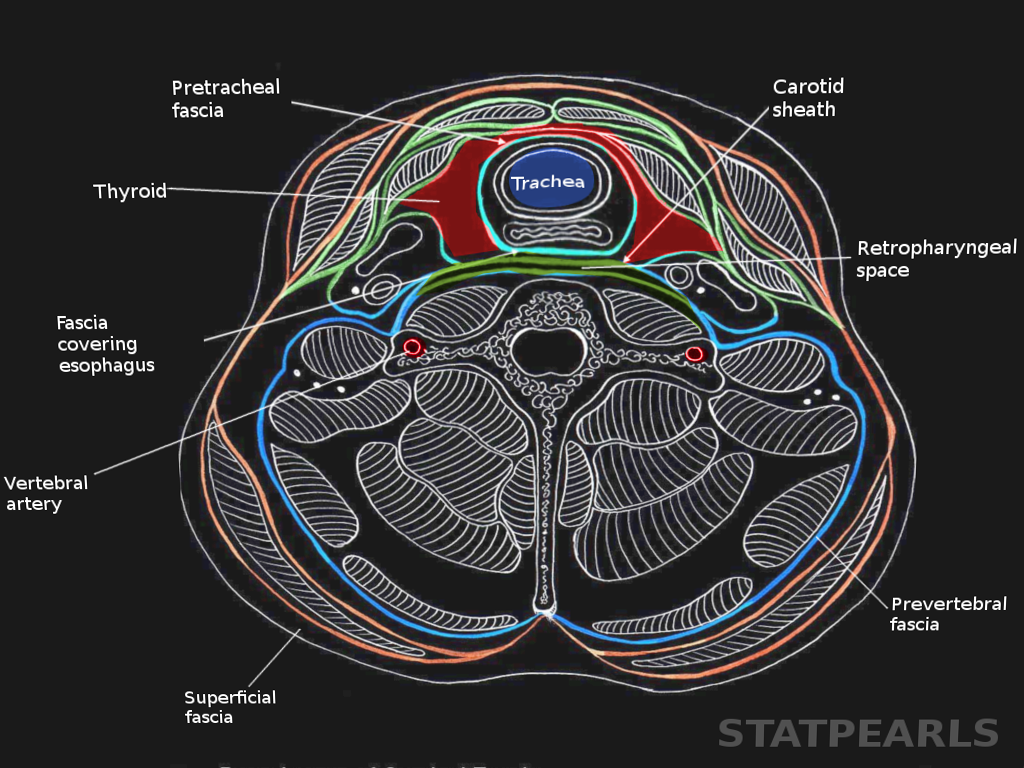

This discussion will consider the topographic morphology of the deep cervical fascia. By this classification system, the deep cervical fascia of the neck can subdivide into the investing layer, pretracheal and prevertebral layers, also known as the external, middle and deep layers respectively. The pretracheal, or middle layer, can be further subdivided into the muscular and visceral divisions. The deep fascia of the neck lies deep to the superficial cervical fascia, a layer that is integral to the subcutaneous tissue and invests the platysma muscle.

The deep fasciae of the neck are anatomic structures with crucial clinical significance for both surgical procedures and in the spread of infection and neoplasia.

Structure and Function

Anatomy of the Deep Cervical Fascia

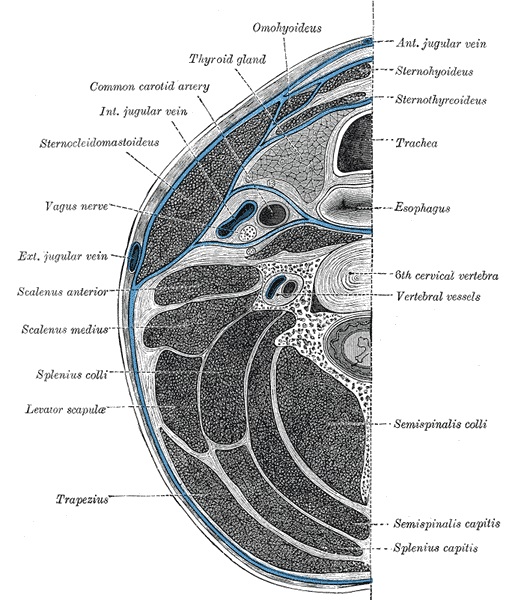

The investing, or external layer attaches to the ligamentum nuchae and vertebral spines posteriorly and extends out laterally and around the neck, encircling it. Anteriorly, it attaches to the hyoid bone and courses further superiorly to enclose the submandibular salivary gland near where it attaches to the inferior surface of the mandible. In this suprahyoid region, between the hyoid bone and the mandible, this layer envelopes the digastric and stylohyoid muscles. Extensions of the investing fascia course superiorly to envelope the parotid gland. It attaches to the skull along a continuous line along the superior nuchal line and mastoid processes of the occipital bone. This line of attachment continues anteriorly, just inferior to the boney external auditory meatus, to the zygomatic process of the temporal bone. The investing fascia of the neck envelopes the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscles anteriorly and trapezius muscles posteriorly. Inferiorly, this facial layer is continuous with the fascia of the pectoralis major anteriorly and with the thoracic portion of the trapezius and latissimus dorsi, posteriorly.[3][4] The investing layer attaches to the manubrium, the clavicles, and the spinous and acromion processes of the scapulae. The existence of the investing fascia across the anterior of the neck, between the SCM muscles, in the area corresponding to the anterior triangles, has been disputed.[5] Additionally, the existence of the investing fascia between the SCM muscles and the trapezius muscles has also been a point of dispute.[6]

The muscular division of the pretracheal, or middle layer, invests the so-called "strap muscles," which are the infrahyoid, geniohyoid, and mylohyoid muscles. Superiorly this layer attaches to the hyoid bone and thyroid cartilage. Inferiorly, on the anterior aspect of the neck, it is continuous with the clavipectoral fascia that surrounds the subclavius, pectoralis minor and serratus anterior muscles,[1] with attachments to the manubrium and clavicles, posterior the attachment site of the external layer of deep fascia.[2] Posteriorly, the muscular division of the pretracheal fascia has been reported by some to be continuous with the prevertebral fascia.[1][7]

The visceral division of the pretracheal layer contains within it the thyroid and parathyroid glands as well as the trachea and esophagus. Its superior attachment anteriorly is to the thyroid cartilage. The posterior segment of this fascia, spanning between each carotid sheath, running behind the esophagus and the posterior portion of the lateral lobes of the thyroid gland, is referred to as the buccopharyngeal fascia. This posterior segment derives its name from its anatomic relation to the pharyngeal and buccinators muscles. It extends superiorly to cover the pharyngeal constrictor muscles and runs anteriorly at this level from the pharynx to cover the buccinators muscle of the face. Posterior to the buccopharyngeal fascia lies the retropharyngeal space. Its superior attachment is to the bones of the base of the skull. Inferiorly this layer is continuous with the fibrous pericardium. The buccopharyngeal fascia continues as the thoracic covering of the esophagus and trachea.[2] In clinical settings, the part of the visceral division of the pretracheal fascia which overlies the thyroid gland and trachea may be referred to as the prethyroid and pretracheal viscera respectively.

The prevertebral, or deep layer of the deep cervical fascia, like the investing fascia, attaches to the ligamentum nuchae and fully encircles the vertebrae, muscles associated with the vertebral column and the cervical portion of the sympathetic trunk ganglia. It extends laterally from its attachment at the ligamentum nuchae to encircle the vertebrae and associated muscles, attaching to the transverse processes of the cervical vertebrae as it courses anteriorly to overlie the scalene muscles anterior to the vertebrae. This layer joins back up with itself anterior to the vertebral bodies, situated posteriorly to the buccopharyngeal fascia. The muscles that lie within the prevertebral fascial layer can be thought of in terms of their location respective to the cervical vertebrae. Lying mostly anterior to the vertebrae, the muscles that lie within this fascial layer are the longus capitis, scalene muscles, and longus coli. Posteriorly, the muscles within this layer are those of the longissimus, semispinalis and splenius muscle groups. The levator scapulae also lie deep to this fascia. The rectus capitis and obliquus muscles, as well as the deep spinal muscles, lie within this layer. The prevertebral fascia sends extensions inward investing all of these muscles which lie deep to it. Superiorly, its attachment is the base of the skull both anteriorly and posteriorly. Some sources report that the prevertebral fascia is continuous with the muscular division of the pretracheal layer and that posteriorly the inferior aspect of this singular fascia is continuous with the fascia of the rhomboid major, rhomboid minor and the serratus posterior muscles with boney attachment to the scapulae.[1][7] Inferiorly, anterior to the vertebrae, the prevertebral fascia is continuous with the anterior longitudinal ligament of the spine. As it descends it also gives off fibers which blend with the fibers of the suprapleural membrane, also known as Sibson fascia. Laterally, it gives off fibers that form the axillary sheath. The prevertebral fascia is continuous with the transversalis fascia of the thorax and abdomen. The prevertebral fascia functions to help in allowing the esophagus, pharynx, and carotid sheaths to glide unobstructed by the longus coli and scalene muscles during neck flexion, extension, and rotation.

The alar fascia is a distinct facial layer that is attached to and lies anteriorly to the prevertebral fascia. It is attached laterally to the prevertebral fascia, where they both attach to the transverse vertebral processes. The alar fascia spans the midline, anterior to the prevertebral fascia and posterior to the buccopharyngeal fascia. Posterior to the buccopharyngeal fascia and anterior to the alar fascia lies the retropharyngeal space. Posterior to the alar fascia and anterior to the prevertebral fascia lies the danger space of the neck. The alar fascia attaches to the base of the skull, like the prevertebral fascia which it overlies anteriorly. Inferiorly the alar fascia joins the buccopharyngeal fascia at about the level of the first or second thoracic vertebra.[2] The existence of the alar fascia has been disputed, but recent evidence supports its existence.[8]

The carotid sheath is a tubular fascial layer that surrounds the common carotid and internal carotid arteries, the internal jugular vein, the vagus nerve and sympathetic nerve fibers traveling in association with the adventitia of the carotid arteries. Fibers from all three deep cervical fascial layers - the investing, pretracheal and prevertebral - give fibers that blend with the carotid sheath. Some sources consider the carotid sheath to be a distinct division of the deep cervical fascia, while others consider it to be a "facial sheath," separate from the true deep cervical fascia.[1][2] Despite this controversy, what research has established is that it is a histologically distinct structure.[9] The sheath is continuous superiorly with the dura mater within the cranial vault, and inferiorly it communicates with the anterior mediastinum.

Deep Spaces of the Neck

The spaces (in reality they are compartments, not true spaces) bound by these fasciae represent important clinical correlates of this basic anatomy topic and have been addressed previously by several authors.[10][11][12] Here, the deep spaces of the neck will be listed, and the anatomy of the more clinically significant spaces will undergo clarification in more detail.

The hyoid bone represents an essential boundary for anterior deep spaces of the neck, dividing these spaces into sub- and suprahyoid regions. Other spaces, more posterior, are not interrupted by the hyoid bone and extend the entire length of the neck. Importantly, many of these spaces extend into the mediastinum. The spaces that span the entire length of the neck further subdivide into superficial and deep. The superficial full-length space is the superficial space. There are four deep spaces of the neck that span the entire length of the neck. These are the retropharyngeal space, the danger space, the prevertebral space and the space within the carotid sheath. The spaces bound inferiorly by the hyoid bone include the submandibular, pharyngomaxillary, masticator, parotid and peritonsillar spaces. The anterior visceral space is the only space that is bound superiorly by the hyoid bone.[2]

The most clinically relevant spaces are the retropharyngeal, danger, and submandibular spaces. The retropharyngeal space lies in the space bound by the alar fascia and buccopharyngeal fascia and consists of loose areolar tissue and lymph nodes. This space is bound superiorly by the base of the skull, laterally by the attachment sites of these fasciae to the transverse vertebral processes and inferiorly where these layers join at about T1 or T2. The danger space lies between the alar and prevertebral fascia. It is bound superiorly by the base of the skull and laterally by the attachment site of the alar fascia to the prevertebral fascia (at the transverse vertebral processes). Inferiorly, the danger space is in free communication with the posterior mediastinum, which extends to the diaphragm. An infection of this space can thus spread to involve the vital organs of the thorax. The submandibular space is bound, in part by the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia. Laterally and anteriorly is bound by the mandible, inferiorly and posteriorly it is bound by the hyoid bone. Superficially, its boundary is the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia, and its superior border is the mucosa of the oral cavity. This space is the area that is involved in Ludwig angina, an infectious process of the floor of the oral cavity often associated with dental infections.[2]

The Function of the Deep Cervical Fascia

The fasciae that are associated closely with muscles serve as a guide for muscular movement. These fasciae also serve, in some cases, as attachment sites for some parts of these muscles. The fasciae which are in close associating with viscera act as structural support and are separate from the organ capsule or the adventitia of the blood vessels which they enclose.

Embryology

The fasciae that are closely associated with the muscles of the neck, as described above, are derived from fibro-muscular laminae during ontogenesis. For example, one fetal anatomy study discovered that the prevertebral lamina develops as an aponeurosis for the longus colli muscles.[13] The visceral fascia develops independently of the organs or vessels which they enclose.[13] The thickness of the fasciae is not genetically determined (excluding cases of connective tissue disorders), but rather, in the adult patient, the fascial thickness is related to the degree of repetitive mechanical stress that the patient may encounter through their life.[1]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Fasciae derive their blood supply from branches of the vessels that supply the structure which they enclose. Arguably more important than blood supply is the relation of the main vessels of the neck to these fasciae. As previously mentioned, the carotid sheath contains the common carotid and internal carotid arteries as well as the internal jugular vein. The vertebral arteries travel through the transverse foramina of the cervical vertebrae which are themselves surrounded by the prevertebral fascia.

The major groups of lymph nodes that drain the mucosal surfaces of the oropharynx and nasopharynx are located deep to the investing fascia and superficial to the pretracheal and prevertebral fasciae and tend to lie in proximity to nerves or vessels that course through this space. The retropharyngeal space contains deeper nodes whereas the danger space does not contain any organized lymph tissue.[14]

Nerves

Several vital nerves descend from the head, through the neck, to a destination elsewhere in the body. The anatomic relationship of such nerves to the deep cervical fascia is essential. The vagus nerve (CN X), travels, for the most part, within the carotid sheath. Sympathetic chain ganglia are deep to the prevertebral fascia, anterolateral to the cervical vertebral bodies. The nerves of the brachial plexus are contained within the prevertebral fascia as they leave the intervertebral foramina. More laterally the brachial plexus are still contained within the same fascia in the form of the axillary sheath: the axillary sheath being continuous with the prevertebral fascia. The recurrent laryngeal nerve, a branch of the vagus nerve, exists within the visceral division of the pretracheal layer, lying on the posterior aspect of the lateral lobes of the thyroid gland. The cervical plexus, like the brachial plexus, leaves the spinal column and enters the space bound by the prevertebral fascia and then extends out laterally, piercing through all three deep cervical layers to innervate the skin.

Innervation of the fasciae is likely significant in the pathophysiology of myofascial pain. In this context, nociceptive fibers that travel with the motor fibers which innervate a particular muscle are possibly involved in pain sensation of the involved muscle and its associated fascia.

Clinical Significance

The clinical significance that the deep fascia had until part way through the previous century primarily revolved around the spread of infection, but with the advent and widespread use of antibiotics, knowledge of the anatomy of these structures has become less important. However, knowledge of the deep spaces of the neck, in particular, the retropharyngeal and danger spaces, are of still of potential clinical significance, particularly in areas of international medicine where vaccine rates and antibiotic use may be lower than in the United States. Additionally, the clinician should have a basic understanding of the relative spatial relationships of the structures within the neck as they relate to the deep fascia.

In a patient presenting with an untreated chronic infection in the nasopharyngeal or cervical areas, who complains of dysphagia, dysphonia, or dysarthria, a clinician should consider an infection in the deep neck spaces. Note that the retropharyngeal space communicates with the superior mediastinum and infection in this space can spread to this area with potentially very serious consequences. The danger space, lying just posterior to the retropharyngeal is in free communication with the posterior mediastinum and infection in this space can likewise spread inferiorly to the mediastinum. The danger space is continuous with the mediastinum to the level of the diaphragm whereas the retropharyngeal spaces does not continue past about T1 or T2 as the alar fascia attaches to the retropharyngeal fascia at this level, forming this area's inferior boundary.

Compared with the spread of infection, a more common clinical scenario that involves the deep cervical fasciae is lymph node removal in cases of metastatic nasopharyngeal cancers. The major lymph node groups of the neck mostly lie in the compartment between the investing and visceral layer anteriorly and between the investing and prevertebral layers posteriorly.