Continuing Education Activity

Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) is a rare but often misdiagnosed corneal infection, primarily affecting contact lens wearers and occasionally resulting from corneal trauma in non–contact lens users. This infection is caused by the Acanthamoeba genus, a globally widespread unicellular protozoan parasite. Key risk factors include trauma, swimming in contaminated water, contact lens use in showers, lack of hygiene, and using contaminated lens solutions. Addressing the challenge of AK involves educating patients about contact lens hygiene and behavior and enhancing contact lens disinfection systems targeting all Acanthamoeba strains. Regulatory considerations for over-the-counter lenses and developing effective diagnostic protocols are crucial. This educational activity emphasizes interprofessional collaboration among eye care professionals, educators, and regulatory bodies to advance patient care for this condition.

Objectives:

Differentiate between Acanthamoeba keratitis and other forms of microbial keratitis, considering distinct etiologies and treatment approaches.

Implement standardized diagnostic protocols, incorporating advanced imaging techniques and laboratory tests, to confirm Acanthamoeba keratitis promptly and accurately.

Select appropriate antimicrobial agents, contact lens disinfection systems, and supportive therapies based on the specific Acanthamoeba strain and its susceptibility, ensuring optimal treatment outcomes.

Coordinate interprofessional care and follow-up to ensure comprehensive treatment and better patient outcomes in Acanthamoeba keratitis.

Introduction

Acanthamoeba is a genus of protozoans widely present in various habitats, including water, air, soil, and dust.[1] Initially identified in 1974, Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) is a sight-threatening ocular infection with a potentially poor prognosis, primarily due to significant delays in diagnosis.[2] The etiology of AK seems multifactorial, with most cases being associated with the use of contact lenses and their cleaning solutions.[3]

In the past 2 decades, there has been a continuous increase in contact lens users coupled with inadequate hygienic practices, elevated risk factors, and improper handling methods, which have led to increased risk of microbial keratitis, especially bacterial keratitis and AK.[4] AK, a painful, sight-threatening condition, profoundly impacts a patient's quality of life.

AK closely mimics other keratitis, often leading to misdiagnosis and delayed treatment. The condition can manifest with a fluctuating course, and nonresolving cases may require therapeutic keratoplasty to preserve vision. AK is a rare corneal pathology with a prevalence of 1 to 9 cases per 100,000 individuals. The incidence of this condition in the Western world is increasing due to its direct association with contact lens usage, which remains the primary risk factor for this condition.[5]

Up to 93% of cases of AK are reported among contact lens wearers, emphasizing the crucial link between this eye infection and contact lens usage. Several risk factors contribute to the occurrence of AK, including inadequate contact lens hygiene, overnight wear, prolonged use, lens use during activities like swimming and showering, exposure to contaminated water, trauma, and the use of contaminated contact lens solution.[6] Disposable contact lens users face an elevated risk, and orthokeratology has also been identified as a contributing factor, with an annual incidence of 7.7 cases per 10,000 individuals.

Acanthamoeba, a free-living protozoan, is omnipresent in freshwater and soil, existing in 2 distinct forms: the dormant cystic form and the motile trophozoite form. The cystic form, characterized by reduced metabolic activity, exhibits resistance against extreme conditions such as temperature variations, dry weather, pH fluctuations, and antiamoebic drugs. Despite advancements in diagnostic and treatment methods, cases of AK are still frequently missed or delayed, leading to detrimental effects on patient outcomes and quality of life. Delayed diagnosis can result in deeper corneal involvement, necessitating urgent keratoplasty to restore ocular anatomy and vision.[6]

Etiology

Acanthamoeba belongs to the phylum Amoebozoa, subphylum Lobosa, and order Centramoebida, as classified in biological taxonomy.[7] Acanthamoeba species demonstrate remarkable adaptability, thriving in diverse environments such as soil and aquatic settings, including ponds, swimming pools, hot tubs, and contact lens solutions. Acanthamoeba species are classified through the 18s rDNA sequence analysis, categorizing them into distinct genotypes labeled T1 to T12.[8] AK is most commonly associated with specities within the T4 genotype.[9] Among the species that cause AK, Acanthamoeba castellani and Acanthamoeba polyphaga are the most frequently identified culprits.[10]

Acanthamoeba species have 2 distinct forms: an active trophozoite and a dormant cyst. The trophozoite form feeds on bacteria, algae, and yeasts. Trophozoites possess slow locomotion abilities and can undergo asexual reproduction.[11][12] In contrast, the cystic form displays minimal metabolic activity and can endure harsh environmental conditions, including drastic temperature or pH fluctuations, high doses of ultraviolet (UV) light, food scarcity, and desiccation.[13]

Epidemiology

The incidence of AK has been rising over recent decades.[14] Despite being traditionally perceived as a rare cause of keratitis, some studies have indicated that Acanthamoeba is responsible for approximately 5% of cases of contact lens-associated keratitis.[15] AK predominantly affects contact lens wearers, with reported rates ranging from 1 to 33 cases per million contact lens wearers annually.[1] The wide variation in incidence is attributed to regional differences in contact lens types, water contamination in domestic and swimming pool environments, and variances in the utilization of diagnostic tests for AK.[16]

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reveal that storing contact lenses in water or topping off solutions increases the risk of AK by 4.46 and 4.38 times, respectively.[17] Despite the common association of poor lens hygiene with the development of AK, this infection may still occur in individuals who properly clean their contact lenses. Most available multipurpose solutions are ineffective against Acanthamoeba,[18][19] with one study demonstrating the efficacy of contact solutions containing hydrogen peroxide against the organism.[20] Furthermore, AK cases have been reported in noncontact lens wearers, particularly individuals with regular ocular exposure to dust, soil, or contaminated water sources.[21]

AK can occur at any age but mainly affects individuals aged 40 to 60 and younger.[22] Individuals with compromised immune systems are at a heightened risk of developing this condition.[23] There is no known sex predilection associated with AK.

Pathophysiology

The initial stages of ocular infection involve the pathogen adhering to the corneal surface through mannose-binding protein and laminin-binding protein interactions.[24][25] The adhesion process sets off phagocytosis and prompts the release of various enzymes and toxins, including neuraminidase, superoxide dismutase, protease, ecto-ATPase, phospholipases, glycosidases, and acanthaporin.[26] Consequently, corneal epithelial destruction and apoptosis occur, facilitating invasion into the stroma.[27][28] Once stromal degradation has occurred, the pathogen can penetrate the cornea. Acanthamoeba proteases may also damage the corneal nerves, leading to severe pain and the characteristic slit lamp examination finding of radial keratoneuritis.[8] Notably, intraocular infection with Acanthamoeba is rare due to the intense response of polymorphonuclear leukocytes in the anterior chamber.[29]

Several factors indirectly contribute to the pathogenicity of Acanthamoeba, including its widespread presence, lack of distinct morphology, ability to tolerate a broad range of temperatures and pH levels, and capacity to reversibly differentiate into cysts or trophozoites.[26] These unique features enhance the adaptability of Acanthamoeba and contribute to its ability to cause ocular infections.

Wearing contact lenses induces microtrauma to the corneal epithelium and upregulates glycoproteins. Soft contact lenses, in particular, possess a more adhesive surface than hard lenses, allowing the Acanthamoeba trophozoite greater access to the cornea.[30][31]

History and Physical

A comprehensive patient history is crucial for all individuals displaying symptoms suggestive of ocular infection. Particular attention should be given to contact lens usage, recent corneal injuries, and dust, soil, or contaminated water exposure. AK typically manifests unilaterally, although it may rarely occur in both eyes.[30] A defining characteristic of AK, even in its early stages, is severe pain disproportionate to the clinical findings believed to be triggered by the activity of trophozoite-derived proteases.[8] Patients commonly complain of reduced vision, eye redness, a foreign body sensation, photophobia, tearing, and discharge. Symptoms may fluctuate in intensity, ranging from mild to severe.[31]

Alarmingly, 75% to 90% of patients with early AK are initially misdiagnosed,[11] underscoring the importance of considering AK in patients where symptoms persist for several weeks without improvement despite strict adherence to a daily regimen of topical antibiotics or antivirals. Clinicians should also be vigilant about the possibility of bacterial superinfection if symptoms worsen despite appropriate treatment initiation.

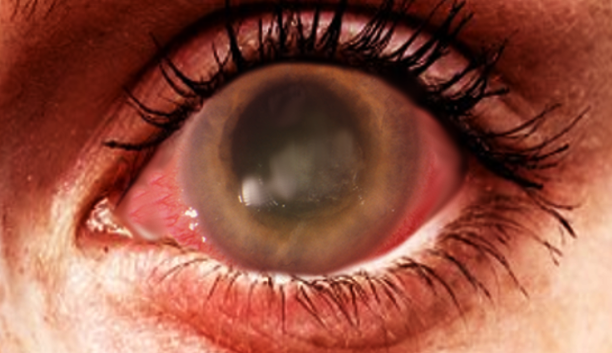

A thorough ocular examination is essential for patients with suspected ocular infections. Early findings during slit-lamp examination often reveal epitheliopathy with punctuate keratopathy, epithelial or subepithelial infiltrates, pseudodendrites, and perineural infiltrates (see Image. Acanthamoeba Keratitis).[1] Perineural infiltrates, highly suggestive of AK, have been observed in up to 63% of cases at 6 weeks, although they may regress as the disease progresses.[32] Late-stage AK is characterized by distinct features on slit-lamp examination, including a "ring-like" stromal infiltrate and radial keratoneuritis. Additionally, satellite lesions, ulceration, abscess formation, anterior uveitis with hypopyon, and epithelial defects are frequently seen.[31] Notably, the characteristic ring infiltrate is found in approximately 50% of patients with advanced disease.[26] Advanced AK can lead to stromal thinning and corneal perforation.[31] Since many of these exam findings are nonspecific, clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion for AK, especially when the patient's history and other features strongly suggest the possibility.

Early Presentation

Epithelial

Epithelial involvement is the most common manifestation observed in 51.1% of patients. Other manifestations include dendritiform epitheliopathy, pseudodendrites, epithelial microcysts, epithelial microcysts, epithelial infiltrates, and epithelial ridges.[33]

- Subepithelial

- Punctate keratopathy

- Subepithelial infiltrates[33]

Late Presentation

- Stromal involvement

- Radial perineuritis is present in 63% of cases

- Ring infiltrates are present in 20% of cases

- Nummular infiltrates

- Diffuse infiltration is seen in 64%

- Corneal melt and perforation

- Hypopyon [5]

- Extracorneal manifestations

- Limbitis

- Scleritis

- Sterile uveitis

- Dacryoadenitis[11]

Acanthamoeba Keratitis Misdiagnosis

Overall, 75% to 90% of AK cases are misdiagnosed. Among these, 47.6% are erroneously identified as herpetic keratitis, 25.2% as mycotic keratitis, and 3.9% as bacterial keratitis.[34]

Evaluation

The plate culture technique has traditionally been considered the gold standard for Acanthamoeba detection. However, recent advancements have highlighted the growing importance of polymerase chain reaction (PCR), in vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM), and staining methods in diagnosis.

Corneal scraping or biopsy is required to obtain a sample for culture. The corneal scrapings are smeared on calcofluor white (CFW) or Gram stain. The cysts present as double-walled structures, with the inner wall appearing hexagonal. Distinguishing trophozoites from inflammatory cells can be challenging.

A key advantage of staining techniques is their ability to provide immediate diagnosis. Gram stain exhibits a sensitivity of 60% and a specificity of 99.9% for cyst detection. In KOH mounts, sensitivity is 91.4%, and specificity is 99.9%. CFW mount displays cysts as light green structures, with a sensitivity of 79.6% and specificity of 100%. Combined KOH and CFW sensitivity is 87.1%. Since Acanthamoeba trophozoites feed on bacteria, cultures develop on 1.5% nonnutrient agar plates covered by E. Coli.[35] However, the rate of positive culture results for Acanthamoeba in AK settings is generally low, ranging from 40% to 70%.[36] Samples require daily observation for up to a week before a negative result can be confidently declared.[26]

Scraping, corneal biopsy, and contact lens solution culture on Nicolle Novy-McNeal (N.N.N.) medium yield a sensitivity of 70%, with results becoming readable after 3 weeks. Immunohistological staining using monoclonal antibodies has demonstrated utility, although this technique is time-consuming and demands the expertise of a skilled microbiologist for interpretation.[37]

PCR has shown significant advancements in detecting Acanthamoeba over the past decade. The 18s rRNA region is the most commonly employed target in clinical samples, with new primer sets demonstrating a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 96%.[37] PCR offers notable advantages, being widely accessible, rapid, and requiring less labor. There is growing speculation that PCR may emerge as the new gold standard for diagnosing AK.[37] PCR is an adjunct to culture and smear methods, providing reports within an hour. Additionally, PCR can detect nonviable Acanthamoeba, enhancing its utility for confirming positive results.

A corneal biopsy is recommended in cases of smear and culture-negative AK with extensive stromal involvement. The reported sensitivity is 56%. When subjected to periodic acid Schiff staining, the corneal biopsy reveals the presence of Acanthamoeba cysts, confirming the infection.

Some authors recommend that clinicians collect the most recent pair of contact lenses and lens cases for culture and PCR.[1] However, nearly all contact lens cases, including those belonging to healthy contact lens wearers, yield positive results for Acanthamoeba on PCR. Consequently, the absence of Acanthamoeba in a culture of a contact lens case strongly indicates a diagnosis other than AK.[26] The definitive diagnosis of AK relies on either culture with histology or PCR to identify Acanthamoeba deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA).

IVCM is an invaluable noninvasive tool that enables real-time examination of individual corneal cells. IVCM reliably detects cysts appearing as well-defined, round, double-walled, hyper-reflective bodies. One study reported a pooled sensitivity and specificity of rates of 85.3% and 100%, respectively, for IVCM. Additionally, IVCM can monitor disease progression and assess treatment response.[36] Despite its effectiveness, IVCM is costly and may not always be readily available.[38]

Another study reported confocal microscopy exhibited a sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 91%. This technique is rapid, noninvasive, and has the capability to identify only double-walled cysts. Alternatively, cytology smears provide a viable method for detecting Acanthamoeba cysts in corneal scrapings or biopsied tissue. Cytology smears offer the advantage of being fast, easily performed, and widely available in most facilities. Unlike culture, cytology smears do not require live organisms or intact DNA as needed for PCR.[38]

Several stains, including lactophenol-cotton blue, Giemsa, CFW, and acridine orange, are commonly used due to their speed and accuracy. However, VFW and Giemsa require a fluorescent microscope and may lead to false positives due to cellular debris staining.[26][39] The silver stain becomes necessary when clinicians require specific cyst morphology. Some evidence suggests that hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining is more sensitive and specific than other stains, especially CFW and Giemsa.[39][40] Notably, there has been at least 1 study where H&E staining enabled the diagnosis of AK even without a positive culture result.[41]

Several innovative diagnostic methods have been employed for diagnosing AK. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) has shown a high sensitivity and specificity, comparable to PCR, in diagnosing AK. Unlike PCR, LAMP amplifies the target sequence at a constant temperature of 60 °C to 65 °C, eliminating the need for an expensive thermal cycler. LAMP could be an alternative to PCR for future AK diagnoses due to its simplicity and affordability.[35] Additionally, researchers have explored noninvasive imaging techniques, including Heidelberg retina tomography II (HRT II) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy.[35] However, further studies are necessary to establish their sensitivity and specificity

Treatment / Management

Acanthamoeba trophozoites display sensitivity to various medications, including antibiotics, antiseptics, antifungals, and antiprotozoals (see Table. Available Drug Therapies for Acanthamoeba Keratitis). However, the cystic form of Acanthamoeba is resistant to most of these treatments, leading to prolonged infections.[1]

Diamidines and biguanides are 2 classes of antiemetics often utilized as first-line therapy for AK due to their proven cysticidal effects. When used individually or in combination, these topical antiemetics exhibit efficacy ranging from 35% to 86%.[32] Medical and surgical options may be considered in cases of treatment-resistant AK.

Table 1. Available Drug Therapies for Acanthamoeba Keratitis

|

Class

|

Mechanism

|

Examples

|

|

Biguanides

|

Inhibit membrane function

|

- Polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB)

- Chlorhexidine

|

|

Aromatic diamidines

|

Inhibit DNA synthesis

|

- Propamidine (brolene)

- Hexamidine

|

|

Aminoglycosides

|

Inhibit protein synthesis

|

|

|

Imidazoles

|

Destabilize the cell wall

|

- Clotrimazole

- Ketoconazole

|

Table 2. Drug Treatment Guidelines for Acanthamoeba Keratitis

|

First Line Therapy

|

Concentration

|

Frequency

|

|

Chlorhexidine

+

Brolene

|

0.02%

0.1%

|

Every hour for 2 to 3 days, then every 1 hour while awake for 3 days, then tapered to 4 times daily. Titrated based on toxicity and response

|

|

Second Line Therapy

|

|

|

|

PHMB

|

0.02% to 0.06%

|

Every hour for 2 to 3 days, then every 1 hour while awake for 3 days, then tapered to 4 times daily

|

|

Hexamidine

|

0.1%

|

|

|

Pentamidine

|

0.1%

|

|

|

Third Line Therapy

|

|

|

|

Imidazoles

|

1%

|

Use hourly during the initial period

|

|

Neomycin

|

10 mg/mL

|

Titrated based on toxicity and response

|

|

Adjunctive Therapy

|

|

|

|

NSAIDs

|

Topical or oral

|

2 to 4 times daily as needed

|

Diamidines exert their therapeutic effect by modifying the structure and permeability of the cell membrane, resulting in the denaturation of cytoplasmic contents (see Table. Drug Treatment Guidelines for Acanthamoeba Keratitis) Propamidine-isethionate, hexamidine-diisethionate, and dibromopropamidine are diamidines used for the treatment of acanthamoeba keratitis at 0.1% concentration.[1] While diamidines are generally well-tolerated, prolonged therapy at the therapeutic level can lead to ocular surface toxicity.[42]

Biguanides function similarly by causing modifications in cytoplasmic membranes, leading to the loss of cellular components and the inhibition of enzymes crucial for cell respiration. Among biguanides, PHMB and chlorhexidine are the 2 most widely used for AK treatment. PHMB is typically initiated at a concentration of 0.02% but can be escalated to 0.06% for AK cases that are unresponsive or severe at the initial presentation. Similarly, chlorhexidine is usually started at a concentration of 0.02% but may be increased to 0.2% if necessary.[1]

PHMB in Comparison with Chlorhexidine

In a randomized controlled trial conducted in the United Kingdom involving 56 eyes, the study concluded that the chlorhexidine group exhibited 86% resolution of infection, control of inflammation, pain relief, and photosensitivity compared to 78% in the PHMB group. Regarding visual acuity resolution, 71% showed improvement in visual acuity in the chlorhexidine group compared to 57% in the PHMB group.

Most modern treatment protocols advocate for initiating combination therapy involving a biguanide and a diamidine. However, recent research indicates that PHMB 0.08% monotherapy is as effective as the combination of PHMB 0.02% and propamidine 0.1%.[43]

Early intensive treatment is more effective since cysts have not yet fully matured.[32] Medications are administered hourly, both day and night, for the initial 48 hours, after which the frequency is reduced to hourly during the daytime for several days to weeks.[1] As the infection subsides, the frequency may further decrease to 4 times daily, a regimen maintained for 6 months to a year.[11][44] The objective of this prolonged therapy is to ensure the complete eradication of Acanthamoeba cysts. Premature treatment discontinuation could allow any remaining dormant cysts to differentiate into trophozoites. Clinicians should tailor treatment plans for each case to minimize risks of epithelial toxicity.[1]

Neomycin was previously a primary treatment for AK because of its anti-trophozoite properties, although it does not seem to reach cysticidal levels in vitro.[32] Nevertheless, neomycin serves a role in preventing bacterial superinfection and reducing bacterial food for trophozoites. Some physicians include topical neomycin 1% 5 times daily as part of an initial triple therapy. This inclusion may have an additive effect when combined with biguanides and diamidines, making it a strategic choice in the treatment regimen.[11][45]

Approximately 39% of patients with AK do not respond to initial therapy. Individuals with more severe clinical presentations or a history of corticosteroid use before diagnosis face a higher likelihood of treatment failure.[14] Numerous other medications can act as adjunct treatments alongside biguanides and diamidines. Miltefosine, recently approved by the Food and Drugs Administration (FDA), is an antiamebic agent that has shown promise as an adjuvant treatment for treatment-resistant AK.[46][47] However, the literature surrounding its use is still evolving, necessitating further studies to clarify its role and establish the optimal timing, dosage, and route of administration.

The therapeutic effectiveness of antifungals appears to be restricted in AK. Among all antifungals, only newer-generation azoles like voriconazole and posaconazole seem to attain cysticidal levels in vitro.[48] However, in vivo, the sustainability of treatment response might be questionable.[49] Natamycin demonstrated better cysticidal effects than PHMB in vitro, although data on its use in animal models is currently unavailable.[50]

Epithelial debridement can enhance the penetration of topical medications.[1] If AK is unresponsive to conservative topical treatment, various surgical options are available, including penetrating keratoplasty (PK), corneal cryoplasty, amniotic membrane transplantation, and riboflavin-UVA cross-linking.[51][52][53] Notably, PK was the first-line therapy for AK before the advent of biguanides and diamidines. PK is typically reserved for patients with significant cataracts, severe corneal abscesses, corneal perforation, or therapy-resistant ulceration with peripheral neovascularization.[32] Following PK, topical treatment should continue for up to 1 year.[11] Therapeutic PK (TPK) has successfully treated medically unresponsive cases of AK, although multiple grafts may be necessary, and the prognosis remains guarded.

Indications for PK include cornea scleral involvement, progressive keratitis, resistance to medical therapy persisting over weeks to months in a disease lasting less than 5 months, nonhealing epithelial defect, and peripheral neovascularization. Deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK) offers a more promising prognosis in eradicating the infection and promoting graft survival. In a study conducted by Sarnicola et al., DALK was performed in 11 cases of AK during therapy, with no episodes of recurrence or failure reported.

Management options for cases resistant to treatment, such as nonhealing epithelial defects, include corneal cryotherapy, amniotic membrane transplantation, PK, and DALK. Cryotherapy is used as an adjunct to PK, applied before recipient trephination. The cold cryoprobe is applied 2 to 3 times (freeze-thaw-freeze), although caution is necessary to prevent affecting the limbal stem cell configuration.[54]

Several promising novel therapeutic approaches are under exploration. A case series involving 4 patients treated with photorefractive surgery showed excellent visual outcomes with no disease recurrence.[55] Other case reports have suggested a role for collagen cross-linking in the management of AK.[56]

Tissue studies have highlighted the cysticidal effect of 3 antidiabetic agents (glimepiride, vildagliptin, and repaglinide) against Acanthamoeba castellanii, particularly when combined with silver nanoparticles.[57] Moreover, the combination of titanium dioxide and UV-A demonstrated a synergistic cysticidal effect against Acanthamoeba species when compounded with chlorhexidine in vitro.[58]

Clinical trials in animal models are necessary to assess the efficacy and safety of these novel therapies. Future research avenues might include exploring genetic markers and delving into stem cell research; however, these endeavors would require a better understanding of the disease at a molecular level.

Developing extracorneal manifestations like scleritis or limbitis signify a more serious condition and warrants treatment with anti-inflammatory medications. Most cases of extracorneal inflammation are manageable with oral flurbiprofen at 50 to 100 mg, taken 2 to 3 times daily.[32] Scleritis or limbitis unresponsive to NSAIDs may benefit from high-dose systemic steroids (prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day), and other systemic immunosuppressive agents such as cyclosporine (3.0 to 7.5 mg/kg/day) may be necessary.[32] These medications may need to be continued for several months to control inflammation and eradicate the pathogen.

The use of topical corticosteroids in AK remains controversial and is discouraged by many physicians. While typically unnecessary in the early stages, topical steroids may be required in significant anterior segment inflammation cases.[1] Steroids should be prescribed judiciously due to the risk of promoting encystment and increasing trophozoite numbers.[11] Clinicians must never prescribe steroids without concurrent administration of antiemetic agents, and antiamoebic therapy should continue for several weeks after discontinuing steroids.[1]

Although topical steroids reduce inflammation, they can transform cysts into trophozoites, worsening the infection. Additionally, steroids mask clinical signs.

Topical steroids are indicated in cases with a progressive increase in deep corneal vascularization or when the patient develops inflammatory complications of AK, such as scleritis, anterior chamber inflammation, persistent chronic keratitis, and severe pain out of proportion to the exam. Corticosteroid therapy is considered after completing at least 2 weeks of biguanide treatment. Antiamoebic therapy must persist even after steroid discontinuation. During follow-up visits, it is crucial to monitor for the infection recurrence. Biguanides are continued at low doses 4 times daily after stopping steroid therapy.

Role of Corneal Collagen Cross-linking

In vivo and in vitro studies have failed to demonstrate a cysticidal or amoebicidal effect. In cases with stromal infiltrates, UV light penetration into the corneal stroma is diminished. The effectiveness of corneal collagen cross-linking with riboflavin (C3R) in AK is still debated.

Differential Diagnosis

One study revealed clinicians initially misdiagnosed nearly half of all AK cases as herpes simplex keratitis (HSK).[59] The pseudodendrites observed in early AK may resemble the epithelial dendrites seen in HSK; however, AK pseudodendrites lack a knot-like widening at the terminal ends of the erosion, a characteristic feature of herpetic dendrites.[11] AK can be differentiated from HSK by the presence of perineural and ring infiltrates, whereas HSK is more likely to involve the endothelium.[26] AK is polymicrobial or coinfected with herpes simplex virus in 10% to 23% of cases.[1]

AK can occasionally be mistaken for bacterial or mycotic keratitis. Ring infiltrates, typically associated with AK, may also appear in bacterial and mycotic keratitis.[11] However, in the absence of a superinfection, AK is more likely to present with multifocal, transparent stromal infiltrate rather than monofocal, thicker infiltrates seen in bacterial and mycotic infections.[11] Moreover, bacterial keratitis is more prone to extend beyond the cornea and involve the anterior chamber.[26]

The multifocal stromal infiltrates observed in AK may resemble the satellite infiltrates of fungal keratitis. However, AK can be differentiated from fungal keratitis during slit-lamp examination by the presence of translucent epithelial defects, perineural stromal infiltrates, and ring infiltrates. Fungal keratitis is more prone to extend beyond the cornea.[26] Additionally, the culture of fungal keratitis would typically yield a positive result on Sabouraud agar.

Unlike patients with uncomplicated bacterial or fungal keratitis, patients with AK tend to be younger and often experience a more extended duration of symptoms at the initial presentation.[60] However, AK has been observed to coexist frequently with bacterial and fungal keratitis.[61] Consequently, the degree to which patients’ demographic factors should be considered in formulating a differential diagnosis remains unclear.

The differential diagnosis for AK includes the following:

- Contact lens-associated keratitis

- Conjunctivitis

- Dry eye

- HSK: presents with dendritic or geographic ulcers

- Recurrent corneal erosion

- Staphylococcal marginal keratitis

- Fungal keratitis: has thicker infiltrates and is typically monofocal

- Bacterial keratitis

The absence of the terminal bulb is a distinguishing feature in AK, where stromal infiltrates manifest as transparent, dot-like, and multifocal. This unique pattern of stromal infiltrates in AK often aids clinicians in accurately diagnosing the condition and differentiating it from other forms of keratitis. Early detection is crucial for prompt and effective management.

Prognosis

The prognosis of AK is heavily influenced by the disease's severity at presentation and the timeliness of effective therapy initiation.[62] Delays in diagnosis often result in corneal scarring, leading to a poor prognosis. However, patients who begin treatment within 3 weeks of symptom onset generally experience favorable visual outcomes.[32]

A worse prognosis is associated with the presence of cataracts or involvement beyond the cornea.[1] Elective PK may be considered for vision improvement, although some experts recommend performing it only after the infection has resolved and treatment has been discontinued for 3 months.[1] There is no reported variation in the prognosis of AK based on the specific Acanthamoeba genus involved.

Complications

Common complications of AK include glaucoma, iris atrophy, broad-based anterior synechiae, cataracts, and persistent endothelial defects. In rare cases, patients may develop complications such as scleritis, sterile anterior uveitis, chorioretinitis, and retinal vasculitis.[11]

Scleritis, observed in approximately 10% of AK cases, is thought to result from an inflammatory response of unknown etiology rather than a direct invasion of Acanthamoeba.[32] Management of extracorneal inflammation involves appropriate anti-inflammatory treatments.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postoperative management of AK aligns with protocols for other microbial keratitis. Following TPK, the patient is initially treated with anti-Acanthamoeba drugs such as PHMB and chlorhexidine, administered 6 to 8 times daily, with adjustments based on the clinical response. In cases with recurrence, the anti-Acanthamoeba therapy can be intensified to use every 1 to 2 hours, continuing for at least 2 to 3 weeks.[26]

Steroids can be introduced 3 weeks later, under the cover of anti-Acanthamoeba drugs, initially administered 3 times daily. If no recurrence is observed, the steroid regimen can be adjusted accordingly:

- Increase to 4 times daily for 3 months, then 3 times daily for 3 months, then 2 times daily for 3 months, then 1 time daily until graft survival

Additionally, adjuvant medications like cycloplegics and antiglaucoma drugs should be incorporated to protect the eye. Examples of medications to consider are as follows:

- Cycloplegics

- Antiglaucoma

Regular and timely follow-up appointments are essential for the patient's ongoing care and recovery.[63] Close monitoring allows for prompt detection of potential complications or recurrence, ensuring that appropriate interventions can be implemented swiftly to optimize the patient's visual outcomes and overall eye health.

Consultations

Patients suspected of having AK should be referred to a cornea specialist for accurate diagnosis and specialized management. Patients who develop cataracts as a complication should be directed to a cataract surgeon for appropriate surgical intervention. Similarly, for cases involving glaucoma, referral to a specialized glaucoma clinic is essential for comprehensive and targeted management of the condition.[11]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients, particularly contact lens wearers, should receive comprehensive education on preventing AK. Education should include avoiding overnight wear of contact lenses, refraining from using homemade saline solutions, and not wearing lenses while swimming or showering. Utilizing daily disposable lenses instead of reusable ones might lower the risk of AK, although this is still unproven.[64]

Individuals regularly exposed to dirt, soil, or contaminated water should wear suitable protective eyewear. Furthermore, enhancing clinician's understanding of Acanthamoeba's pathogenesis could significantly benefit patient care.[32]

Pearls and Other Issues

Key facts to keep in mind about AK are as follows:

- AK is a rare and challenging condition to diagnose and treat. Clinicians should maintain a high suspicion for AK when encountering cases of keratitis unresponsive to standard first-line treatments. Being vigilant in considering this possibility is crucial for accurate diagnosis and timely intervention.

- Most cases involving AK develop in contact lens wearers. While inadequate lens hygiene is often cited, it is worth noting that many multipurpose solutions are ineffective against Acanthamoeba.

- On slit-lamp examination, AK is characterized by ring-shaped infiltrate and radial keratoneuritis. Notably, ring-shaped infiltrates are typically observed in the advanced stages and found in only 50% of patients.

- Biguanides and diamidines are the first-line treatments for AK. The utilization of topical corticosteroids is controversial and discouraged by most physicians.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients displaying symptoms suggestive of ocular infection are likely to consult their primary care physicians or visit the emergency department. Consequently, these healthcare practitioners must know about AK and its distinctive presentation. Direct referral to a cornea specialist, as opposed to other ophthalmologists, significantly reduces the likelihood of treatment failure, with 3.2 times lower odds associated with this approach.[14]

Effective communication among the pathologist, cornea specialist, and microbiologist is crucial for implementing isolation techniques essential in identifying Acanthamoeba. Primary care clinicians, including nurses and pharmacists, educate patients on proper contact lens hygiene. Patients should be advised to remove contact lenses during water-related activities, use fresh storage solutions, and practice thorough handwashing before touching their contacts. Immediate consultation with an eye specialist is strongly recommended if a patient wearing contact lenses develops eye redness, pain, or photophobia.

Pharmacists are integral in coordinating with treating clinicians to ensure appropriate agent selection, dosing, and monitoring for drug interactions. Ophthalmology-specialized nurses can verify compliance, monitor therapeutic progress, and remain vigilant for adverse events. To facilitate optimal outcomes in managing AK, pharmacists and nurses should maintain an open communication channel with prescribers, enabling them to address any issues promptly. Effective interprofessional collaboration is fundamental for achieving optimal results in the management of AK.