Continuing Education Activity

Pathologic fractures occur secondary to altered skeletal physiology and mechanics in the setting of a benign or malignant lesion. Therefore, proper diagnosis, staging, and treatment of pathologic fractures are essential to improve patient outcomes. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of pathologic fractures and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in managing patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Review the common symptoms and physical exam findings associated with pathologic fractures.

- Outline the approach to the staging workup for the causative lesion resulting in a pathologic fracture.

- Summarize the surgical approach to fixation for pathologic fractures based on anatomic location and healing potential.

- Explain the importance of collaboration and communication amongst the interprofessional team to improve outcomes for patients affected by pathologic fractures.

Introduction

Pathologic fractures represent a growing concern in the field of musculoskeletal oncology. The incidence of pathologic fractures is rising, primarily due to improved diagnosis and treatment of metastatic disease leading to prolonged survival. Therefore, diagnosis of the causative pathology is of paramount importance in the successful treatment of a pathologic fracture and is a prerequisite for proceeding with surgical intervention. Pathologic fractures occur through areas of weakened bone attributed to either primary malignant lesions, benign lesions, metastasis, or underlying metabolic abnormalities, with the common factor being altered skeletal biomechanics secondary to pathologic bone.

Etiology

The majority of neoplastic pathologic fractures are caused secondary to metastatic disease rather than primary bone tumors. In a patient 40 years of age or older, the likelihood that a pathologic fracture through an unknown lesion that is metastatic is 500 times more common than the likelihood of it being a primary bone sarcoma.[1] There are five recognized carcinomas that most frequently metastasize to bone, including lung, breast, thyroid, renal, and prostate. The most common sites for skeletal metastasis include the spine, proximal femur, and pelvis.[2][3] Primary bone sarcomas occur far less frequently, though disregarding the possibility that a pathologic fracture through a solitary bone lesion could be the first evidence of a primary sarcoma could lead to catastrophic consequences, including loss of life or limb.

Epidemiology

Approximately 1.7 million people are diagnosed with cancer each year in the United States.[4] Metastatic disease of the bone will affect approximately 5% of these patients, varying based on cancer type, with the cost of healthcare being nearly 13 billion dollars.[5] Approximately 8% of these patients will sustain a pathologic fracture, based on a retrospective analysis by Higinbotham on 1,800 patients with metastatic cancer to bone.[6] Primary soft tissue and bone sarcomas are far less common, affecting roughly 13,000 and 3,600 people in the U.S., respectively.[4]

Pathophysiology

Osteolytic lesions of bone occur secondary to tumor-induced activation of osteoclasts by upregulation of RANK ligand.[7] Osteoblastic lesions occur secondary to endothelin 1, which is secreted by the tumor.[8] Pathologic fractures occur through these lesions due to altered biomechanics. For example, a lytic lesion or open-section defect might produce a stress concentration that cannot withstand normal or low-demand activity.[9]

Histopathology

Histology varies based upon the source of the primary malignancy. In general, lesions are graded as low, intermediate, or high grade. The grade of the lesion is determined by the degree of cellular atypia, pleomorphism, active mitosis, matrix production, and necrosis. Lower-grade lesions are biologically less aggressive, while higher-grade lesions are more aggressive and are hence prone to further spread and metastasis.[10]

History and Physical

Pathologic fractures can be preceded by lesions producing prodromal pain or can be indolent until the time of fracture. Patients may or may not report B symptoms, including unintentional weight loss, fevers, etc. Patients may also report symptoms specific to the particular primary carcinoma, such as urinary abnormalities with renal cell carcinoma or shortness of breath and/or cough with lung carcinoma. Patients may additionally report symptoms of hypercalcemia of malignancy, which could masquerade as mild confusion and gastrointestinal abnormalities to cardiac arrhythmia and renal failure.

Physical exam should include a focused assessment of the extremity or a spinal exam when warranted. Careful attention should be paid to neurovascular examination, though the compromise is uncommon in pathologic fractures of the extremities.

Evaluation

When a pathologic fracture is identified through a lesion of unknown origin, a comprehensive workup must be conducted to identify the etiology and stage of the disease.

Laboratory analysis should include a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel (with special attention to serum calcium and alkaline phosphatase), prothrombin/INR, activated partial thromboplastin, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, urinalysis, urinary protein electrophoresis, and serum protein electrophoresis. Disease-specific markers, including prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), etc., may also be considered. Laboratory abnormalities may exist secondary to malignancy and may elucidate the source of malignancy. For example, a urinalysis may provide some insight into the primary pathology. If hematuria is present, renal cell or uroepithelial carcinoma should be considered. If Bence-Jones proteins are present, multiple myeloma is likely the diagnosis. Pregnancy tests should also be obtained in women of child-bearing age prior to imaging.

Radiological analysis of pathologic fractures begins with orthogonal radiographs of the fracture site and the involved bone in its entirety. A plain radiograph is the single most important imaging modality and provides the most information about a pathologic lesion. There are a number of aggressive features suggestive of a pathologic lesion that may be identified on X-ray, which include: lesion diameter > 5 cm, cortical interruption, periosteal reaction, and associated pathologic fracture. A chest radiograph should also be obtained. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with oral and intravenous contrast should be obtained for staging purposes. Whole-body bone scintigraphy should also be obtained. Bone scans are particularly useful for identifying osteoblastic activity. If laboratory analysis has confirmed the diagnosis of multiple myeloma, a skeletal survey may be obtained in lieu of a bone scan, which might fail to identify the degree of osteolysis present in other sites. This comprehensive strategy is the gold standard and is successful in identifying the origin of the lesion in 85% of cases.[10]

Advanced imaging of the extremity may be included for preoperative planning or if there is a concern for primary bone sarcoma. Other reasons to obtain local CT imaging are to evaluate the degree of osteolysis and to better understand the 3-dimensional anatomy of lesions, particularly in locales with complex dimensional anatomy such as the pelvis. Reasons to consider magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the extremity include evaluation of the degree of soft-tissue involvement as well as neurovascular involvement. Consider mammography for indicated patients when a primary breast carcinoma cannot be excluded. Positron emission tomography is becoming more popular and is highly sensitive for identifying infection and malignant tumors. The specificity of positron emission tomography alone is only 30%, though it increases to 50% when combined with computed tomography.[11]

A biopsy is performed following the completion of laboratory and radiological workup. There are six recognized reasons to complete a staging workup prior to biopsy:

- The tumor may be a primary bone sarcoma. Therefore, a staging workup would prevent poorly placed biopsy location or trajectory.

- There may be an additional site of metastasis that is more easily accessible and/or associated with less morbidity than the site of the pathologic fracture.

- Pre-operative embolization may be required for intraoperative hemostasis.

- An unnecessary biopsy may be avoided altogether if the diagnosis may be made via laboratory analysis alone, such as with multiple myeloma.

- Histologic analysis in isolation identifies the source in only 3% of cases.

- A combination of pre-operative imaging and laboratory studies with histopathology increases the likelihood that the correct diagnosis will be made.[1]

There are three types of biopsy, including fine-needle aspiration (FNA), core-needle biopsy, and open biopsy, with advantages and disadvantages to each. Open biopsies are further subclassified as incisional or excisional. Principles of biopsy of bone lesions have been well-documented and should adhere to strict guidelines.[12] Guidelines include a biopsy through a single compartment via a longitudinal incision without damage to neurovascular structures, in line with the planned surgical incision while maintaining hemostasis throughout. Any deviation from these guidelines will lead to unnecessary surgical field tumor contamination.

Treatment / Management

Treatment algorithms exist for both impending fractures and pathologic fractures and generally involve operative fixation combined with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy.

Impending Pathologic Fractures

An impending fracture is a biomechanically weakened area of bone that has a propensity to fracture with far less force than would be required for the normal bone to fracture due to the pathophysiology of the underlying lesion. For instance, normal weight-bearing through a pathologic lesion could tip the scales towards a pathologic fracture due to the biomechanical fragility of the surrounding bony architecture. Impending fractures may require prophylactic fixation, meaning surgical intervention in the form of internal fixation prior to a fracture event as a means of augmenting inherently weak bone and preventing future failure.

There are two recognized classification systems for impending pathologic fractures:

- Harrington criteria was first described by Harrington et al. in 1980 to determine indications for prophylactic internal fixation. Harrington criteria is based on four parameters: lesion involves more than 50% of cortical bone, the lesion is greater than 2.5 cm, presence of pain following radiotherapy, and fracture of the lesser trochanter. There are significant limitations to this grading system as it only applies to the proximal femur and does not account for disease-specific tumor pathology.[13]

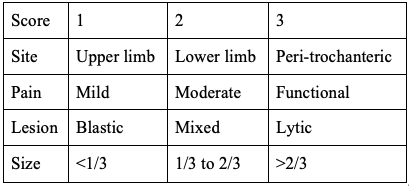

- Mirel classification was first described by Mirel in 1989 and has been extrapolated as an algorithm for prophylactic fixation. The study was a retrospective analysis of 78 lesions of long bones that had undergone radiation therapy without prophylactic internal fixation. This scoring system is depicted in Table 1. This scoring system has a maximum of 12 points, with more than 8 points indicating the need for prophylactic fixation.[14]

Recently, there has been an interest in alternative scoring systems such as CT-based structural rigidity analysis (CTRA). A study by Damron et al. in 2016 evaluated CTRA compared to Mirel’s criteria in pathologic femoral fractures and found CTRA to have a higher predictive value in identifying impending fractures.[15]

The benefits of prophylactic fixation of an impending fracture are two-fold. Elective fixation removes pain and morbidity associated with a true pathologic fracture and facilitates easier surgical management.[16]

Pathologic Fracture

Pathologic fractures may occur secondary to benign lesions, metastasis, primary bone lesions, or metabolic bone abnormalities. Treatment of pathologic fractures is dictated by the pathophysiology of the causative lesion and the expected survival.

Fracture healing rates, prognosis, and patient activity level must be considered to determine the extent of fixation. It is important to recognize that altered disease biology leads to decreased or destroyed fracture healing potential. For example, the fracture healing rates for metastasis from multiple myeloma, renal, breast, and lung carcinoma are 67%, 44%, 37%, and 0%, respectively. This variation of fracture healing potential across different malignancies highlights the importance of proper diagnosis of the primary lesion for successful preoperative planning. For example, a fracture through a lesion secondary to myeloma has a much greater healing potential than one through a lesion secondary to lung carcinoma. Therefore, a construct involving plates and screws might be sufficient for a myeloma-induced fracture, whereas a more extensive bone-replacing prosthesis would be necessary for a fracture induced from lung cancer.[1]

For renal cell carcinoma, metastases should be widely excised when possible. A review of 887 patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma revealed a statistically significant improvement in cancer-specific survival (4.8 years versus 1.3 years) when complete metastasectomy was performed.[17] An additional retrospective study by Higuchi et al. on patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma to bone showed a significant improvement in overall survival and recurrence-free survival for patients undergoing wide resection as compared to local curettage. This same study also revealed that intralesional resection was an independent risk factor for poor prognosis and was associated with significantly more intraoperative blood loss.[18]

In terms of survivability, there are established rates of 6-month survival documented in the literature. For example, 6-month survival for prostate, breast, renal, and lung are 98%, 89%, 51%, and 50%, respectively.[1] Additionally, activity levels must be taken into account. A patient who is wheelchair- or bed-bound requires different fixation than a patient still ambulating and/or weight-bearing through the involved extremity. Recently, there have been leaps of innovation in the fields of artificial intelligence and machine learning, which have helped form models for predicting patient survival. PATHFx 3.0 is one such tool that has been externally validated to estimate the likelihood of survival at 1-month, 3-month, 6-month, 12-months, 18-months, and 24-months after treatment for patients with symptomatic skeletal metastases using a Bayesian belief analysis.[19]

Differential Diagnosis

- Stress fracture: Cortical disruption and/or weakening of bony architecture secondary to repetitive micro-trauma or overuse.

- Paget’s disease: Metabolic disorder resulting in mixed blastic/lytic lesions of bone.

- Avascular necrosis: Local ischemia to a region of bone resulting in tissue death.

- Benign fracture: Cortical disruption secondary to mechanical failure of bone without evidence of malignancy.

- Infection: The presence of foreign microorganisms invading and multiplying within a bone leading to bone erosion and damage.

Surgical Oncology

Surgical intervention for a pathologic fracture should only be considered following an exhaustive oncological work-up and biopsy of the lesion. General principles of internal fixation are applicable but may differ when a fracture of pathologic nature is involved. For instance, implant selection should generally adhere to the following guidelines:

- Load-sharing as opposed to load-bearing when possible

- Durable implants with the goal of lasting the length of patient survival with disease progression

- Immediate stability allowing for immediate weight-bearing

- Length of implant should bypass the lesion by two cortical diameters

- Cement augmentation when necessary

There are particular considerations for implant choice. Titanium implants are typically used in benign fractures because they are MRI-compatible, allowing for future imaging with less artifact than stainless steel. Biomechanically, titanium is more similar to the normal bone than stainless steel in terms of the modulus of elasticity. In pathologic fractures, however, the surrounding bony architecture is inherently weaker than normal bone and may, in certain cases, require stainless steel implants, which are stronger than titanium but preclude future advanced imaging due to increased artifact. More recently, carbon fiber implants have become an area of interest due to their radiolucency, improved fatigue strength, and modulus of elasticity that is more similar to the normal bone than any metal. A study by Zimel et al. compared carbon-fiber-reinforced polyetheretherketone (CFR-PEEK) with titanium intramedullary nails. There was significantly less implant artifact on MRI associated with carbon fiber implants compared with titanium.[20]

For hip arthroplasty procedures, the choice of utilizing cement versus uncemented press-fit implants is widely debated. Advantages of cement include immediate fixation in pathologic bone without the need for waiting for bony in-growth of the implant. Disadvantages of cement include pulmonary complications such as bone cement implantation syndrome (BCIS), allergic reactions, prolonged surgical time, and increased difficulty with any revision surgery where cement needs to be removed. A retrospective study by Larsen et al. on oncologic patients undergoing either cemented or uncemented hip arthroplasty revealed no difference in terms of complication rate, 30-day mortality, intraoperative blood loss, or functional outcome.[21] Ultimately, it is up to the surgeon's personal preference to decide whether to cement when performing hip arthroplasty.

Embolization should be considered prior to operative fixation of pathological fractures to maintain hemostasis for highly vascular tumor subtypes. Embolization is performed by interventional radiology and involves percutaneous embolization of large feeding vessels supplying tumors with polyvinyl alcohol, coils, or gel foam. Well-known malignancies that have a tendency for greater intraoperative blood loss include renal and thyroid cancer, in which case preoperative embolization should be considered. A study by Pazionis et al. evaluated the use of preoperative embolization in renal and thyroid carcinoma. They found that patients who underwent embolization had decreased surgical times, blood loss, and transfusion requirements compared to patients who did not undergo embolization.[22]

Primary sarcomas are aggressive tumors that require wide-excision with a goal of obtaining a cure, as compared to pathologic fractures due to metastatic disease, which are treated as a palliative measure. It is important to properly diagnose the lesion prior to surgery in order to avoid iatrogenic dissemination of a sarcoma, which may result in the loss of a limb that otherwise might have undergone a limb-sparing procedure.

Surgery Based on Tumor Location

The following will report general guidelines for surgical procedures based on anatomic location within the skeleton. These are general guidelines only and may not necessarily be ideal, depending on a multitude of factors. Every tumor and patient poses a unique problem that requires an individualized approach.

Upper Extremity

Generally speaking, fractures of the upper extremity are less debilitating than fractures in the lower extremity as they are under lower stress and are not essential for weight-bearing. Pathologic fractures most commonly occur in the proximal humerus and humeral shaft. The following are general recommendations for fixation of pathologic fractures in particular anatomic locations of the upper extremity:

- The humeral head and anatomic neck of the humerus: shoulder hemiarthroplasty versus total shoulder arthroplasty versus reverse total shoulder arthroplasty versus endoprosthesis versus fixed-angle plate with void filler

- The surgical neck of the humerus to the proximal-third humeral shaft: fixed-angle locking plate

- Humeral diaphysis: locked antegrade intramedullary nails versus plate

- Distal humerus (less common): parallel bridge plating versus distal humeral replacement with total elbow arthroplasty

- Radius/ulna (uncommon): plating versus excision

Lower Extremity

Pathologic fractures of the lower extremity occur much more commonly than in the upper extremity and are of greater clinical significance due to the necessity for weight-bearing. The following are general recommendations for fixation of pathologic fractures in particular anatomic locations of the lower extremity:

- Femoral head and neck: hemiarthroplasty versus total hip arthroplasty versus endoprosthesis versus plate or nail fixation with void filler

- Intertrochanteric, subtrochanteric, diaphyseal fractures: cephalomedullary nails

- Distal third femoral shaft: locking plate versus retrograde intramedullary nail (a musculoskeletal oncologist must carefully consider any retrograde nailing before proceeding to avoid proximal tumor spread)

- Supracondylar: distal femur periarticular plate

- Proximal tibia: locking plate versus endoprosthesis

- Tibial shaft: intramedullary nail

Pelvis

Smaller lesions or fractures of the ischium and pubis may be treated non-operatively with radiation or radiofrequency ablation. Larger lesions involving weight-bearing portions of the pelvis must be treated more aggressively. Generally, impending or pathologic fractures to the pelvis are treated as follows with the possible addition of cement to fill large defects.

- Sacral ala: sacroiliac screws

- Posterior ilium: column screws

- Extensive posterior pelvic ring disruption: spinopelvic fixation

- Anterior column: anterior column screws

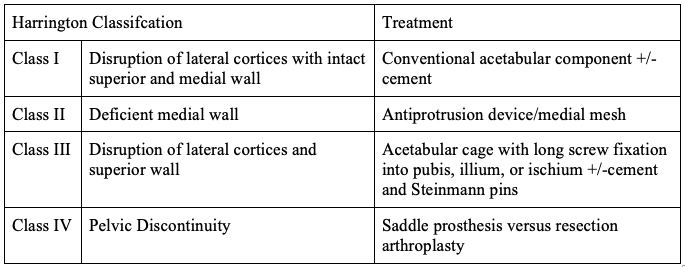

A Classification was devised by Harrington for the treatment of peri-acetabular defects, as depicted in Table 2.[23] A peri-acetabular lesion with intact subchondral bone can undergo curettage and cement without more extensive management.[24]

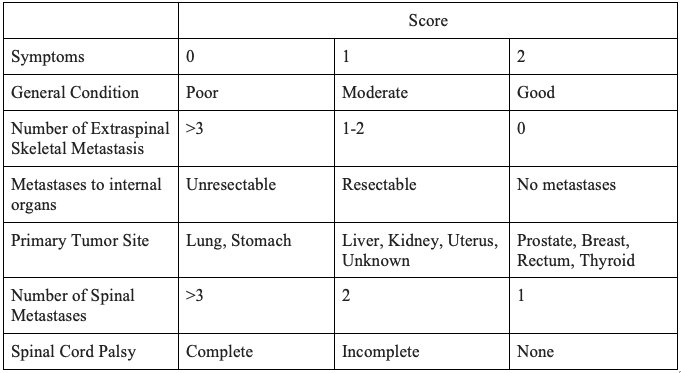

Spine

The spine is the most common site of skeletal metastasis.[25] The decision to pursue surgical intervention for spine metastasis is multi-faceted and entails considerations of pain level, stability, and neurological deficits. Similarly, the goals of surgical intervention of the spine include palliation, decompression of neural elements, and stabilization. Multiple algorithms have been developed regarding surgical decision-making with regards to spine metastasis. An algorithm developed by Tokuhashi et al. is used for the prediction of postoperative survival, as depicted in Table 3. A score of greater than 9 points is indicative of greater than 12 months survival and argues for operative intervention, whereas a score of 5 or less indicates less than 3 months' survival and is an argument against operative intervention.[26]

Radiation Oncology

Radiotherapy is generally performed on an adjuvant or postoperative basis to prevent local disease progression. Radiosensitive tumors include myeloma, lymphoma, prostate, breast, ovarian, and neuroendocrine. Radioresistant tumors include sarcomas, renal, thyroid, hepatocellular, colon, lung, and melanoma.[27] In rare cases, radiotherapy may be performed as a palliative measure in lieu of surgical intervention in patients with severe comorbidities or very poor prognosis. A study evaluating radiotherapy in myeloma found that radiation therapy contributes to pain relief, with complete relief observed in 31% of patients and partial relief in 54% of patients.[28] A single fraction of 8 Gy has been noted to be as effective as multiple fractions of radiation.[29]

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

Radiation-induced fractures are rare but can occur secondary to altered skeletal physiology. They most frequently occur in association with radiotherapy for soft tissue sarcomas. These fractures can occur at any time in life, and thus a patient must undergo surveillance for the remainder of her/his life postoperatively.[30] Other complications that may occur include wound healing complications, local tissue necrosis, and radiation-induced sarcoma. O'Sullivan's randomized control study on patients with extremity soft tissue sarcoma revealed a 35% infection rate for patients receiving preoperative radiation versus 17% for postoperative radiation.[31] Still, preoperative radiation is sometimes favored as it allows for a more focused field with lower doses of radiation.

Medical Oncology

The role of chemotherapy varies based on the primary malignancy. Certain malignancies are chemosensitive, while others are chemoresistant. Generally, chemotherapy protocols are devised using multiple agents. Chemotherapy, when indicated, may be performed in the neoadjuvant (preoperative) or adjuvant (postoperative) setting. Risks and benefits of chemotherapy must be considered in light of a patient's comorbidities, age, and functional status. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) has devised a useful classification scale, which is commonly considered when making a decision to proceed with chemotherapy. The scale runs from 0-5, as follows: 0-asymptomatic, 1-symptomatic but ambulatory, 2-<50% in bed, 3->50% in bed, 4-bedbound, and 5-death.[32]

Staging

There are two staging systems commonly utilized for skeletal metastasis, the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society/Enneking staging system, and the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system.

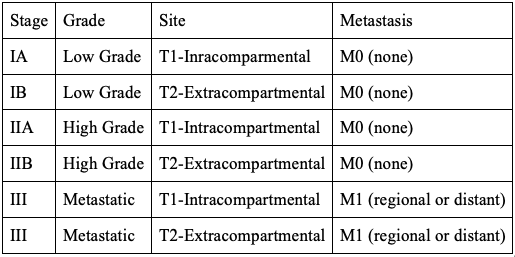

The MSTS/Enneking staging system can be used for both malignant and benign lesions. Malignant lesions are described using Roman numerals, whereas benign lesions are defined by Arabic numbers. The staging system is based on 3 categories: histological grade of tumor, intracompartmental versus extracompartmental location, and presence of metastasis. The staging system is depicted in Table 4.[33]

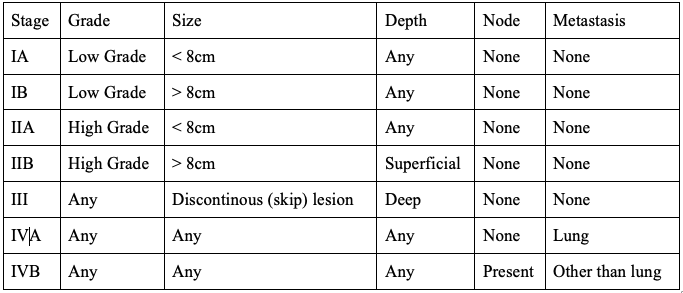

The AJCC Staging System is based upon 5 categories: histological grade, tumor size, depth, nodal involvement, and presence of metastasis. The staging system is depicted in Table 5.[34]

Prognosis

The survival rates for the metastatic bone disease are determined by the primary malignancy. For example, the 6-month survival rates for common malignancies with skeletal metastasis are as follows: lung cancer 50%, renal cancer 51%, breast cancer 89%, and prostate cancer 98%.[1] The 5-year survival rates for localized soft tissue sarcomas are 83% versus 16% in systemic disease.[35] The five-year survival for bone sarcoma is 68%.[36] Pathologic fractures secondary to bone disease occur with varying frequency depending upon the primary lesion and relative function of the patient. Pathologic fractures secondary to osteosarcoma occur in 5% to 12% of patients. Pathologic fractures in the setting of osteosarcoma were previously thought to portend a worse prognosis due to the potential for fracture hematoma to disseminate the pathology, but this has since been disproven.[37]

Complications

A myriad of complications can arise secondary to pathologic fractures and their surgical management. From a surgical standpoint, failure of fixation or reconstruction can occur secondary to poor healing potential or local progression of the disease. Hardware can become infected, which requires long-term antibiotics and/or removal of hardware and revision depending on patient prognosis. Additionally, complications such as deconditioning or venous thromboembolism may arise secondary to poor mobility during the recovery period. There are five accepted modes of failure specific to endoprostheses, as described by Henderson et al. Type 1: soft tissue failure. Type 2: aseptic loosening. Type 3: structural failure. Type 4: periprosthetic infection. Type 5: tumor progression.[38] If cement is used, complications related to underlying allergy or pulmonary sequelae have been reported.[39][40] Bone cement implantation syndrome (BCIS) refers to clinical sequelae characterized by hypoxia and hypotension shortly after pressurizing cement within the bone. This syndrome has been reported in up to 75% of oncologic patients undergoing cemented hip arthroplasty and may be fatal if not managed appropriately.[41]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

The goal of surgery for pathologic fractures is early mobilization and function. Patients undergoing surgical fixation for pathologic fractures will ideally undergo physical therapy immediately following surgery and will mobilize quickly using a targeted protocol with the goal of being weight-bearing as tolerated in most cases. Patients who have had lower-extremity surgery should be placed on anticoagulation postoperatively. Anticoagulation may be warranted for upper extremity cases as well due to the increased risk of venous thromboembolism in the setting of malignancy.

Long-term bisphosphonates or denosumab should be seriously considered to minimize the risk of skeletal-related events (SREs) and prevent hypercalcemia of malignancy. Skeletal-related events are defined as the presence of one of the following criteria: 1) radiation or surgery to bone, 2) pathologic fracture, 3) spinal cord compression, or 4) hypercalcemia of malignancy.[42] Of note, patients who experience an SRE may or may not be symptomatic. Without bisphosphonates, the incidence of SREs in patients with metastatic disease is staggering.

A retrospective review of 718 patients with metastatic breast carcinoma from 1981-1991 revealed the presence of SREs in over 50% of patients.[43] Similar rates can be seen for metastatic prostate, lung, and myeloma. Another study reported an SRE occurring every 3-6 months on average for patients with metastatic disease.[44] With bisphosphonate administration, the incidence of SREs has been dramatically reduced while the length of time between SREs has increased. One study noted a reduction in SRE incidence of 31%, 36%, and 41% for metastatic lung, prostate, and renal cell carcinoma, respectively, with bisphosphonate use.[45] Still, these benefits should be weighed against the risks of bisphosphonates, which include hypocalcemia, jaw osteonecrosis, and atypical fractures, among others.

Consultations

Treatment of pathologic fractures requires an interprofessional approach, and consultations should be obtained from internal medicine, hematology-oncology, radiation-oncology, and palliative care when indicated. These teams should fully optimize patients prior to any elective surgical intervention. Interprofessional meetings involving musculoskeletal oncology, pathology, and radiology are essential in establishing a diagnosis and treatment plan.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Proper staging of malignancy with evaluation for skeletal metastasis should be performed as part of the routine workup of a malignancy. Patients must be educated regarding symptoms of bony metastasis and that early treatment of impending pathologic fractures facilitates an easier postoperative rehabilitation course than a completed pathologic fracture.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Proper diagnosis and staging of the primary malignancy resulting in impending or pathologic fracture are essential for successful treatment.

- An interprofessional approach is required using a combination of medical specialties and treatment methods.

- Different principles of fixation apply for fractures based on anatomic location, healing potential, the patient's level of function, and prognosis.

- The goal of surgical fixation of pathologic fractures is early stabilization, mobilization, and return to function with a robust surgical construct that will outlast a patient's lifetime.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with impending or pathologic fractures secondary to skeletal malignancy or metastasis require an interprofessional diagnostic work-up and treatment approach. All patients should undergo proper diagnosis and staging of the malignancy. Close attention should be paid to abnormal laboratory values or other comorbidities secondary to the malignancy that may require intervention. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy should be initiated when indicated. Surgical treatment should be devised to individually suit the patient and lesion with the goal of early mobilization and return to function. Overall, a patient-centered approach should be utilized.