Public Health Considerations Regarding Obesity

Public Health Considerations Regarding Obesity

Introduction

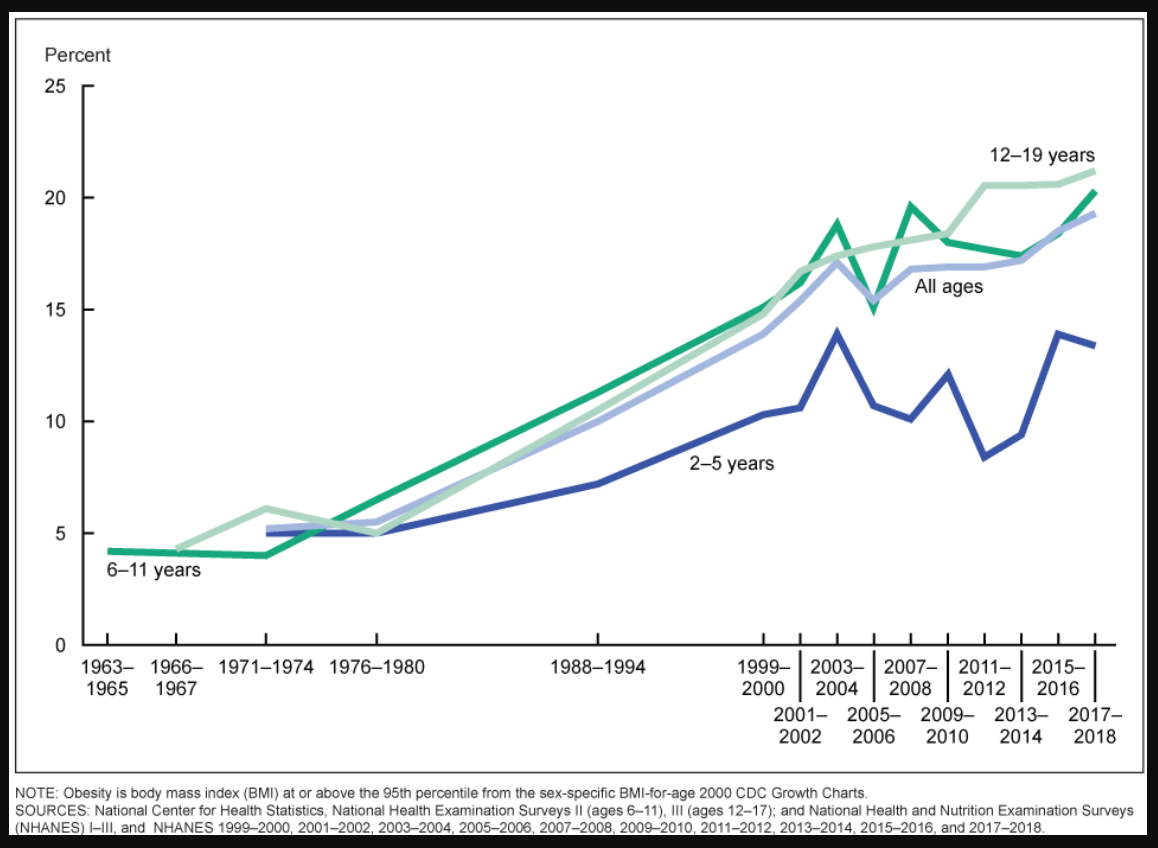

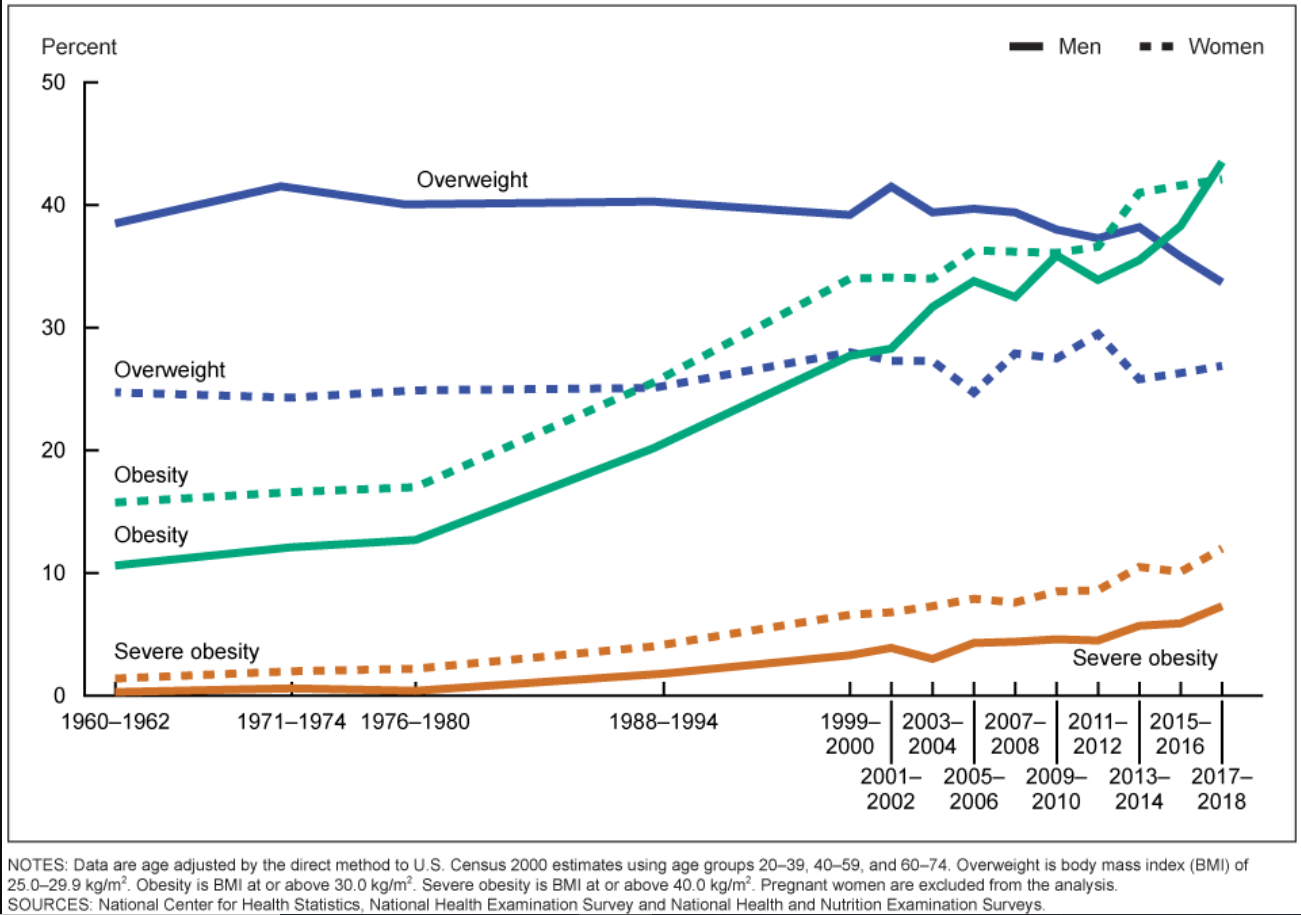

Obesity is increasing as a global public health issue. It affects 2 in 5 adults and 1 in 5 children in the United States and has been characterized as an epidemic.[1][2][3] Several countries worldwide have witnessed a doubling or tripling in the prevalence of obesity in the last 3 decades (see Images. Obesity Trends in Children and Obesity Trends in Adults), likely due to urbanization, sedentary lifestyles, and increased consumption of high-calorie processed foods.[4]

The alarming increase in childhood obesity forecasts a significant burden of chronic disease worldwide. Obesity prevention is critical in controlling obesity-related noncommunicable diseases (OR-NCDs), including type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance/metabolic syndrome with hyperinsulinemia, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, metabolic-associated fatty liver disease, and coronary artery disease.[5][6]

The failure of traditional obesity prevention and control measures underscores the need for a new, nonstigmatizing public health policy model. This approach shifts the focus from solely targeting individual behavior changes to implementing strategies that address broader environmental factors contributing to obesity. Weight bias and discrimination against people with obesity exist in public settings, eg, workplaces, healthcare facilities, and schools, and must be confronted on a societal level.

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

Public Health Impact of Obesity

Obesity is a growing global public health challenge with far-reaching effects on individuals and society. The public health impact of obesity extends beyond physical health, influencing life expectancy and quality of life and contributing to economic and employment burdens. The following are the various impacts of obesity on individual and public health:

- Life expectancy: Obesity causes serious illness and decreases the average life expectancy. Adult obesity strongly predicts early death. The Framingham Heart Study, a prospective cohort study, revealed that adults who were obese at 40 years lost 6 to 7 years of their expected lifespan. However, in obese people who smoked, the years of life lost almost doubled.[7][8]

- Quality of life: Obesity affects both the physical and psychosocial aspects of quality of life, even more significantly in individuals with class 3 obesity. The subjective Health-related quality of life (HRQL) assessment among individuals with obesity worsens with increasing body mass index (BMI). The effect of obesity on HRQL is assessed most often by the Short-Form Health Survey, comprising 36 questions covering 8 domains, including physical functioning, physical limitations in daily activities, social functioning, bodily pain, general mental well-being, limitations due to emotional problems, energy levels and fatigue, and overall perception of health.[9][10] The risk of a chronic medical condition nearly doubles in people with class 3 obesity compared to individuals with overweight.[11] Obesity causes a substantial psychological burden exacerbated by society's preoccupation with thinness. Sullivan et al reported more significant psychosocial consequences in women with obesity than in men.[12]

- Prevalence of obesity-associated diseases: Individuals who are obese in childhood tend to remain obese in adulthood and are prone to OR-NCDs at a younger age.[13] These include type 2 diabetes, coronary artery disease, stroke, cancer, asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which have increased worldwide along with the prevalence of obesity. These conditions are the primary targets of the World Health Organization (WHO) global disease prevention.[14] Compared with their healthy-weight peers, individuals with class 2 obesity lose about 8 disease-free years of life, and those with class 1 obesity lose about 4 disease-free years.[15]

- Employment: Obesity is one of the leading reasons for discrimination in the hiring process, more among women than men.[16] Obesity can lead to underemployment and an increase in self-reported work limitations compared to healthy-weight individuals.[17]

- Economic impact: Obesity and its complications account for greater than 20% of annual healthcare expenditures in the United States.[18][19] Medical costs are 30% to 40% higher among individuals with obesity than their healthy-weight peers, double the increase attributable to smoking.[20] The direct costs of obesity include spending on diagnosing and treating obesity and obesity-related chronic comorbid conditions, eg, cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. Indirect costs arise from lost wages due to illness and premature death, higher expenses for disability and insurance claims, and reduced productivity at work.

- Physical functioning: Obesity can impair the ability to perform physical activities, including mobility and activities of daily living.

- Physical health: Physical health problems associated with obesity can limit individuals' ability to perform expected tasks at work or at home.

- Mental health: Mental health issues (eg, anxiety or depression) can affect the ability to perform work or daily activities. Emotional well-being, including happiness, anxiety, and overall mood, can impact those with obesity at higher rates than their healthy-weight peers.

- Social functioning: The ability to engage in social activities and interact with others can be diminished.

- Bodily pain: The Intensity of pain can impact daily functioning.

- Energy: Decreased energy level or fatigue may impair daily functioning.

- General health perceptions: Overall perception of health, including current health status and future outlook, may be appropriately low in individuals with obesity.

Clinical Significance

The WHO describes obesity as excessive fat accumulation. A body mass index BMI ≥25 kg/m2 is considered overweight, and a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 is labeled obesity. The relative risk of death increases with increased BMI. This association is nonlinear, with a higher relative risk of death for individuals with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m².[21]

The stigma of obesity deters individuals from utilizing healthcare resources that could prevent morbidity and identify complications early. For example, people with obesity have lower rates of age-appropriate preventive cancer screening.[22][23] Women with obesity delay accessing routine gynecological cancer screening due to perceived social barriers.[24] This reduction in preventive healthcare adds to the burden of morbidity and all-cause mortality. A lack of comprehensive health maintenance care imposes an additional burden on the healthcare system to manage the comorbidities of obesity, which might have been prevented.

Other crucial issues likely affect the obesity burden, including perinatal factors, eg, maternal antenatal BMI, neonatal birth weight, child nutrition in the first 3 years of life, infant feeding choices (breastfeeding versus formula feeding), and the growth pattern in the first year.[25]

Other Issues

Assessing and addressing the barriers that patients with obesity face, which delay obtaining recommended preventive healthcare, is imperative. Health and social inequalities result when efforts to prevent obesity are impaired.[26]

Public Health Policy and Environmental Changes

Societal and environmental changes are the best initiatives for preventing the burden of obesity. Public policy initiatives that can be implemented to change behaviors, leading to healthier dietary and exercise choices include:

- The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued regulations mandating calorie and nutrition labeling in all food products.

- In 2015, the FDA officially banned trans fats in all food in restaurants and grocery stores.

- Obesity prevention priorities can focus on children, particularly in schools, encouraging healthy habits. Local governments can restrict commercial permits for fast-food restaurants near schools (within 0.5 miles) and promote healthy foods in school meals.[27]

- School policies should mandate physical education classes and develop plans for safe ways to walk or bicycle to school.

- Levying taxes on unhealthy food and subsidizing healthy choices are strategies to prevent obesity but may encounter ethical limitations regarding personal choice. Taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages, eg, soft drinks, have been successfully levied in many states and cities.[28][29]

- Public health policy can focus on designing activity-friendly communities by creating bike and walking paths and safe green spaces for outdoor activities.

Family-Based Interventions

The family-based approach is the best intervention to sustain weight loss and weight maintenance among patients with overweight or obesity. Often, several members in a household would benefit from weight loss, and individuals find it challenging to change their lifestyles without family cooperation and support.

No one weight-loss diet has been proven superior. Some studies advocate a low-fat diet with high protein and low glycemic index foods to maintain weight loss and prevent weight regain.[30][31] Other plans include the Mediterranean or DASH diets, intermittent fasting, or a ketogenic diet. An easy-to-use tool in family-based dietary intervention is the traffic light diet, in which food is classified as green, red, and yellow based on health benefits.[32] Whatever the strategy, success depends upon ongoing support and close follow-up to ensure an appropriate plan for each family.

Weight Bias in Health Care

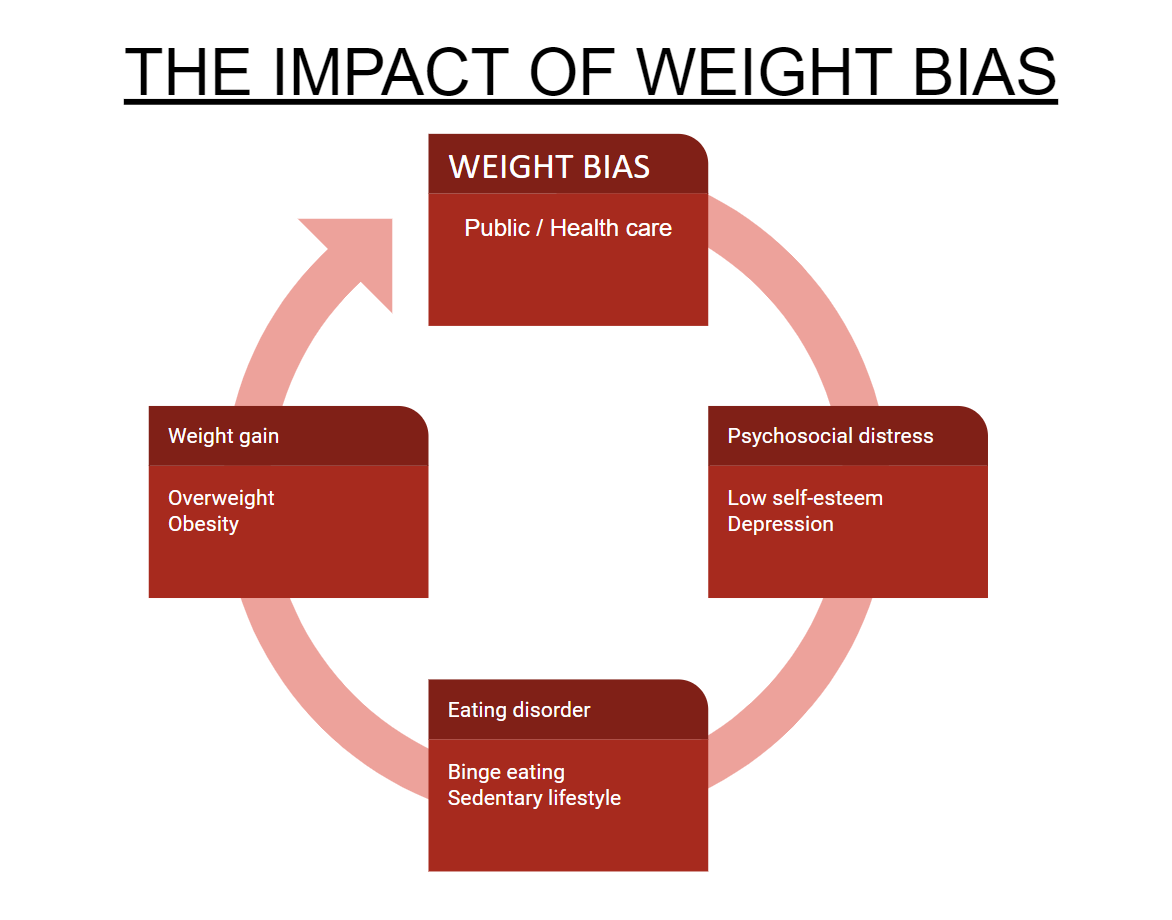

Weight bias in health care can be explicit (consciously expressed) or implicit (involuntarily expressed). Implicit weight bias is not rare among clinicians, as society's negative biases towards overweight and obesity are often shared and exhibited by caregivers (see Image. Impact of Weight Bias). This weight bias can impair the quality of health care. Many clinicians promote the energy balance theory of weight control, believing that obesity is the fault of an individual, which limits effective counseling and intervention.[33][34] The following recommendations can reduce weight bias in healthcare:

- Educate healthcare professionals about the complex etiology of obesity, including genetic, metabolic, environmental, and social factors.

- Inform clinicians that weight bias negatively influences the quality of care.

- Train students in healthcare professions to communicate without implicit bias.

- Another strategy is to expose counter-stereotypical exemplars of people with obesity who are successful and intelligent.

- Address patients' overall health, addressing their understanding of obesity-associated comorbidities and desire for weight loss management.

- Use people-first language, eg, "patients with obesity" instead of "obese patients." Objective terminology, including "high BMI" or "class 1, 2, or 3 obesity," rather than descriptions, eg, "morbid obesity," shows respect and promotes communication in clinical settings.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Addressing obesity effectively requires a coordinated, interprofessional approach to patient-centered care. Primary care physicians play a crucial role in diagnosing obesity, monitoring weight and BMI, and encouraging preventive screenings during health maintenance visits. Nurses, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants are essential in providing follow-up care, supporting patients, and motivating families to adopt healthier lifestyles. Dietitians develop personalized nutrition plans that consider cultural preferences and coexisting health conditions, while exercise specialists recommend age-appropriate physical activity for individuals and families. Behavioral counselors address psychological factors that contribute to maladaptive eating patterns, and school-based health groups support children with obesity and emotional challenges.

For pediatric obesity care, consultation with specialists such as pediatric endocrinologists, obesity experts, and surgeons may be necessary. Public health policymakers play a pivotal role in creating nonstigmatizing, preventive strategies to address the global obesity epidemic. Collaboration among clinicians, policymakers, and community resources is vital to reduce barriers to treatment and ensure welcoming, accessible healthcare environments for individuals with obesity. This interprofessional coordination enhances patient safety, care quality, outcomes, and overall team performance, ultimately addressing the complex public health challenge of obesity.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Li M, Gong W, Wang S, Li Z. Trends in body mass index, overweight and obesity among adults in the USA, the NHANES from 2003 to 2018: a repeat cross-sectional survey. BMJ open. 2022 Dec 16:12(12):e065425. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-065425. Epub 2022 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 36526312]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity Among Adults: United States, 2017-2018. NCHS data brief. 2020 Feb:(360):1-8 [PubMed PMID: 32487284]

Hu K, Staiano AE. Trends in Obesity Prevalence Among Children and Adolescents Aged 2 to 19 Years in the US From 2011 to 2020. JAMA pediatrics. 2022 Oct 1:176(10):1037-1039. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.2052. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35877133]

Boakye K, Bovbjerg M, Schuna J Jr, Branscum A, Varma RP, Ismail R, Barbarash O, Dominguez J, Altuntas Y, Anjana RM, Yusuf R, Kelishadi R, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Iqbal R, Serón P, Rosengren A, Poirier P, Lakshmi PVM, Khatib R, Zatonska K, Hu B, Yin L, Wang C, Yeates K, Chifamba J, Alhabib KF, Avezum Á, Dans A, Lear SA, Yusuf S, Hystad P. Urbanization and physical activity in the global Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiology study. Scientific reports. 2023 Jan 6:13(1):290. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-26406-5. Epub 2023 Jan 6 [PubMed PMID: 36609613]

Henry FJ. Obesity prevention: the key to non-communicable disease control. The West Indian medical journal. 2011 Jul:60(4):446-51 [PubMed PMID: 22097676]

Misra A, Khurana L. Obesity-related non-communicable diseases: South Asians vs White Caucasians. International journal of obesity (2005). 2011 Feb:35(2):167-87. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.135. Epub 2010 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 20644557]

Peeters A, Barendregt JJ, Willekens F, Mackenbach JP, Al Mamun A, Bonneux L, NEDCOM, the Netherlands Epidemiology and Demography Compression of Morbidity Research Group. Obesity in adulthood and its consequences for life expectancy: a life-table analysis. Annals of internal medicine. 2003 Jan 7:138(1):24-32 [PubMed PMID: 12513041]

Ghosh S, Paul M, Mondal KK, Bhattacharjee S, Bhattacharjee P. Sedentary lifestyle with increased risk of obesity in urban adult academic professionals: an epidemiological study in West Bengal, India. Scientific reports. 2023 Mar 25:13(1):4895. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-31977-y. Epub 2023 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 36966257]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceReinbacher P, Draschl A, Smolle MA, Hecker A, Gaderer F, Lanner KB, Ruckenstuhl P, Sadoghi P, Leithner A, Nehrer S, Klestil T, Brunnader K, Bernhardt GA. The Impact of Obesity on the Health of the Older Population: A Cross-Sectional Study on the Relationship between Health-Related Quality of Life and Body Mass Index across Different Age Groups. Nutrients. 2023 Dec 22:16(1):. doi: 10.3390/nu16010051. Epub 2023 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 38201881]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCoulman KD, Blazeby JM. Health-Related Quality of Life in Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery. Current obesity reports. 2020 Sep:9(3):307-314. doi: 10.1007/s13679-020-00392-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32557356]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDoll HA, Petersen SE, Stewart-Brown SL. Obesity and physical and emotional well-being: associations between body mass index, chronic illness, and the physical and mental components of the SF-36 questionnaire. Obesity research. 2000 Mar:8(2):160-70 [PubMed PMID: 10757202]

Sullivan M, Karlsson J, Sjöström L, Backman L, Bengtsson C, Bouchard C, Dahlgren S, Jonsson E, Larsson B, Lindstedt S. Swedish obese subjects (SOS)--an intervention study of obesity. Baseline evaluation of health and psychosocial functioning in the first 1743 subjects examined. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders : journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 1993 Sep:17(9):503-12 [PubMed PMID: 8220652]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBalasundaram P, Krishna S. Obesity Effects on Child Health. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 34033375]

GBD 2016 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet (London, England). 2017 Sep 16:390(10100):1151-1210. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32152-9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28919116]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNyberg ST, Batty GD, Pentti J, Virtanen M, Alfredsson L, Fransson EI, Goldberg M, Heikkilä K, Jokela M, Knutsson A, Koskenvuo M, Lallukka T, Leineweber C, Lindbohm JV, Madsen IEH, Magnusson Hanson LL, Nordin M, Oksanen T, Pietiläinen O, Rahkonen O, Rugulies R, Shipley MJ, Stenholm S, Suominen S, Theorell T, Vahtera J, Westerholm PJM, Westerlund H, Zins M, Hamer M, Singh-Manoux A, Bell JA, Ferrie JE, Kivimäki M. Obesity and loss of disease-free years owing to major non-communicable diseases: a multicohort study. The Lancet. Public health. 2018 Oct:3(10):e490-e497. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30139-7. Epub 2018 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 30177479]

Flint SW, Čadek M, Codreanu SC, Ivić V, Zomer C, Gomoiu A. Obesity Discrimination in the Recruitment Process: "You're Not Hired!". Frontiers in psychology. 2016:7():647. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00647. Epub 2016 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 27199869]

Tunceli K, Li K, Williams LK. Long-term effects of obesity on employment and work limitations among U.S. Adults, 1986 to 1999. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.). 2006 Sep:14(9):1637-46 [PubMed PMID: 17030975]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFinkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2009 Sep-Oct:28(5):w822-31. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w822. Epub 2009 Jul 27 [PubMed PMID: 19635784]

Cawley J, Biener A, Meyerhoefer C, Ding Y, Zvenyach T, Smolarz BG, Ramasamy A. Direct medical costs of obesity in the United States and the most populous states. Journal of managed care & specialty pharmacy. 2021 Mar:27(3):354-366. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2021.20410. Epub 2021 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 33470881]

Spieker EA, Pyzocha N. Economic Impact of Obesity. Primary care. 2016 Mar:43(1):83-95, viii-ix. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2015.08.013. Epub 2016 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 26896202]

Pajak A, Topór-Madry R, Waśkiewicz A, Sygnowska E. Body mass index and risk of death in middle-aged men and women in Poland. Results of POL-MONICA cohort study. Kardiologia polska. 2005 Feb:62(2):95-105; discussion 106-7 [PubMed PMID: 15815793]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFerrante JM, Ohman-Strickland P, Hudson SV, Hahn KA, Scott JG, Crabtree BF. Colorectal cancer screening among obese versus non-obese patients in primary care practices. Cancer detection and prevention. 2006:30(5):459-65 [PubMed PMID: 17067753]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMitchell RS, Padwal RS, Chuck AW, Klarenbach SW. Cancer screening among the overweight and obese in Canada. American journal of preventive medicine. 2008 Aug:35(2):127-32. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.03.031. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18617081]

Amy NK, Aalborg A, Lyons P, Keranen L. Barriers to routine gynecological cancer screening for White and African-American obese women. International journal of obesity (2005). 2006 Jan:30(1):147-55 [PubMed PMID: 16231037]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDaley SF, Balasundaram P. Obesity in Pediatric Patients. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 34033388]

Puhl RM, Heuer CA. Obesity stigma: important considerations for public health. American journal of public health. 2010 Jun:100(6):1019-28. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.159491. Epub 2010 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 20075322]

Davis B, Carpenter C. Proximity of fast-food restaurants to schools and adolescent obesity. American journal of public health. 2009 Mar:99(3):505-10. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.137638. Epub 2008 Dec 23 [PubMed PMID: 19106421]

Zhang Q, Liu S, Liu R, Xue H, Wang Y. Food Policy Approaches to Obesity Prevention: An International Perspective. Current obesity reports. 2014 Jun:3(2):171-82. doi: 10.1007/s13679-014-0099-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25705571]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceReeve E, Farrell P, Thow AM, Mauli S, Patay D. Why health systems cannot fix problems caused by food systems: a call to integrate accountability for obesity into food systems policy. Public health nutrition. 2024 Nov 7:27(1):e228. doi: 10.1017/S1368980024001848. Epub 2024 Nov 7 [PubMed PMID: 39508093]

Larsen TM, Dalskov S, van Baak M, Jebb S, Kafatos A, Pfeiffer A, Martinez JA, Handjieva-Darlenska T, Kunesová M, Holst C, Saris WH, Astrup A. The Diet, Obesity and Genes (Diogenes) Dietary Study in eight European countries - a comprehensive design for long-term intervention. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2010 Jan:11(1):76-91. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00603.x. Epub 2009 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 19470086]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMcMillan-Price J, Petocz P, Atkinson F, O'neill K, Samman S, Steinbeck K, Caterson I, Brand-Miller J. Comparison of 4 diets of varying glycemic load on weight loss and cardiovascular risk reduction in overweight and obese young adults: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of internal medicine. 2006 Jul 24:166(14):1466-75 [PubMed PMID: 16864756]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBrown RD. The traffic light diet can lower risk for obesity and diabetes. NASN school nurse (Print). 2011 May:26(3):152-4 [PubMed PMID: 21675296]

Foster GD, Wadden TA, Makris AP, Davidson D, Sanderson RS, Allison DB, Kessler A. Primary care physicians' attitudes about obesity and its treatment. Obesity research. 2003 Oct:11(10):1168-77 [PubMed PMID: 14569041]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLudwig DS, Apovian CM, Aronne LJ, Astrup A, Cantley LC, Ebbeling CB, Heymsfield SB, Johnson JD, King JC, Krauss RM, Taubes G, Volek JS, Westman EC, Willett WC, Yancy WS Jr, Friedman MI. Competing paradigms of obesity pathogenesis: energy balance versus carbohydrate-insulin models. European journal of clinical nutrition. 2022 Sep:76(9):1209-1221. doi: 10.1038/s41430-022-01179-2. Epub 2022 Jul 28 [PubMed PMID: 35896818]