Standards and Evaluation of Healthcare Quality, Safety, and Person-Centered Care

Standards and Evaluation of Healthcare Quality, Safety, and Person-Centered Care

Introduction

Health care encompasses services and products provided to individuals who are both patients in the traditional sense and customers in a modern context. This activity emphasizes the delivery of health care in both capacities. Therefore, the term patient-customers is used throughout to reflect this dual role. Healthcare providers should consider this concept when engaging with this topic and delivering care, ensuring a balanced approach that prioritizes both clinical outcomes and patient experience.

The history of quality delivery in health care dates back to the earliest texts on physician ethical obligations.[1][2] Please see StatPearls' companion resources, "Medical Ethics" and "Patient Rights and Ethics," for more information. Since the European Enlightenment, the use of objectively measured data to assess and improve healthcare quality has become increasingly common. Another key goal of quality management is the standardization of practices and products once a defined quality threshold has been met. Ernest Codman (1869-1940) is a notable pioneer in both areas. As a surgeon who began practicing medicine in 1895, he initiated record-keeping of surgical outcomes to enable retrospective analysis of processes and their impact on outcomes. To achieve practice standardization, he played a leading role in the American College of Surgeons (ACS) and its Hospital Standardization Program, which eventually became the Joint Commission (TJC) on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Another pioneer in healthcare quality is Ignaz Semmelweis (1818-1865), who established the practice of antisepsis in hospitals. Both Codman and Semmelweis were rejected and harassed by other clinicians for insisting that the status quo was detrimental to patients.[3][4]

The deliberate study, quantification, and practical application of data to achieve quality in business originated outside of health care and remains a distinct field of study outside of health care. While working in telecommunications engineering, Walter Shewhart (1891-1967) pioneered modern statistical process control. Edwards Deming (1900-1993), a physicist who later became a business consultant and a professor of statistics and business, expanded Shewart's work and has been called the originator of quality management.[5] Deming is most recognized for his impact on quality control in automobile manufacturing, and healthcare professionals later adopted his principles.[6] Quality control measures in modern healthcare are often influenced by the work of one or more of these 4 individuals.

Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Function

The function of quality management, including healthcare quality management, is to improve quality through certain techniques described below. Quality management is a simpler and historically earlier version of evolved into the scientific method. Quality management shares the goal of increasing objectivity and reducing subjectivity in decision-making with the scientific method. Both quality management and the scientific method involve the following:

- Defining a problem or issue of interest

- Quantifying one or more dependent variables exposed to a process or event (an independent variable)

- Analyzing how outcomes in the dependent variables differed after exposure

- Concluding what the measurements mean (their significance)

These steps can be repeated, forming what is known as a quality process cycle. Different people divide the cycle into different numbers of steps, such as the Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) with 4 steps or Define Measure Analyze Improve Control with 5 steps.

While the scientific method attempts to disprove a null hypothesis, identify/eliminate data collection biases, and quantify the degree of mathematical certainty for a finding, quality management uses simpler methods to measure processes and identify ways to achieve a more successful outcome. Quality management can reduce bias in data collection and interpretation by evaluating multiple episodes of similar events, also known as factorial designs or design of experiments. However, individuals involved in quality management typically do not conduct true experiments with randomized control groups, which help eliminate bias and confounding variables. Thus, quality management techniques typically do not achieve true experimental evidence (often called level 1 evidence when it involves randomizing test cases). Quality management techniques are typically adequate to determine which of two processes is better or when a process should be altered to reach an objective. Quality management goals typically do not require the scientific method to precisely quantify (1) the degree to which one process is better than another or (2) the strength of the relationship between an independent and a dependent variable.

Quality management focuses on process monitoring and control. According to Deming, quality managers should assess every component of a process (subprocesses) that can result in delays and inconsistencies among individuals and systems. In addition to using lists of subprocesses, quality managers use lists of priorities. For example, Taiichi Ohno, who is credited with the development of the Toyota Production System and its lean management strategy, prioritizes 3 items to eliminate, which include the following:

- Muda ("futility")

- Mura ("inconsistency")

- Muri ("overburdening")

Common reasons managers may still neglect to implement quality management include the following constraints:

- Limited access to reliable data to measure structures, processes, or outcomes

- Inability to design experiments to compare new and existing processes effectively.

- Lack of statistical expertise to quantify confidence in differences between groups.

- Insufficient time to conduct PDSA cycles while managing daily responsibilities, with reluctance to hire additional support.

- Preoccupation with resolving immediate issues (putting out fires) rather than focusing on long-term improvements.

- Superiors who do not perceive sufficient benefits to justify the costs of implementing PDSA cycles.

- A mindset resistant to change, either due to contentment with current operations (If it ain't broke, don't fix it) or a focus solely on outcomes rather than process improvement (The ends justify the means).

Issues of Concern

Definition of Quality

Deming defined quality in business as the delivery of a predictable, uniform standard in services or goods with the standard both suited to and defined by the customer. Although the concept of quality specifies consistency, processes must also adapt to retain standards or achieve new standards based on developments in knowledge and external factors. Such factors include the following:

- New customer demands

- The discovery of better practices developed elsewhere

- New rules from regulatory bodies

Quality can be defined using the following equation:

- Quality = process outcomes × customer satisfaction

This equation measures process outcomes using hard (objective) data, and customer satisfaction is based on perceptual (qualitative) data. Philosophically and linguistically, it can be argued that cost is irrelevant to quality. Deming considered quality as a process that minimizes costs, but he viewed cost control as an end of other quality management means rather than its primary goal.

Value, in equation form, can be defined as follows:

- Value = quality/costs

In other words, healthcare quality includes all factors contributing to patients' health status and their acceptance of the care received. These factors include hard/factual outcomes, such as mortality and morbidity complications, and soft outcomes, such as patient experience. Patients assess quality and value based on their perceptions, whether accurate or not. Perceived quality depends on the patient-customer's observations of the following:

- The effort and care provided by the healthcare provider

- The actual outcome of the treatment or care received

- The time, money, and effort the patient-customer invested in obtaining care

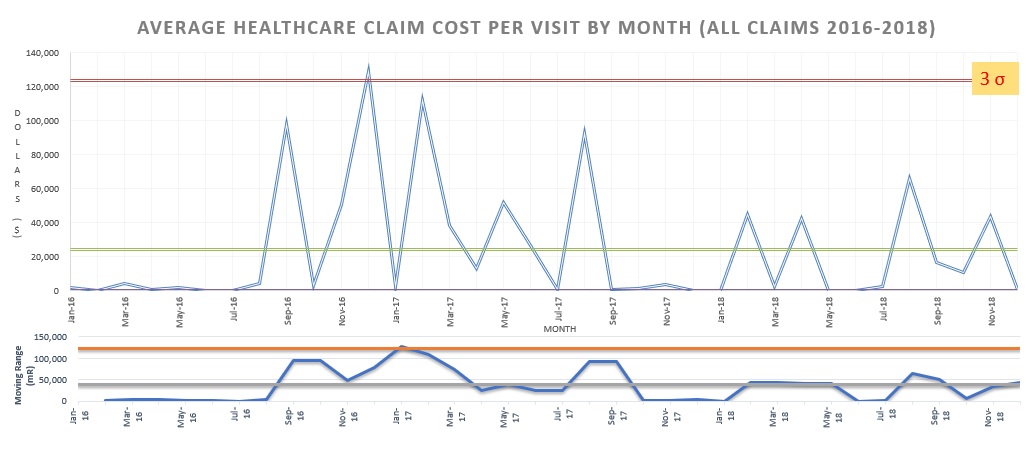

To maximize value, healthcare managers must find ways to increase the positive hard outcomes and the softer perceptual measures while decreasing overall costs (see Image. Average Costs to a Managed Care Organization). Hard and soft quality measures can be evaluated within specific domains, including effectiveness, efficiency, timeliness, safety, equity, and customer-centeredness, or through other models, such as the model based on the work of Avedis Donabedian, discussed below.[7]

Evaluation of Healthcare Quality

Although some individuals praise American health care as the highest in quality, data indicate that American healthcare providers have significant room for improvement. The Commonwealth Fund, which publishes free healthcare performance metrics on its website, released its most recent update in 2024 regarding the healthcare performance of 10 developed nations. The United States ranked last in overall health outcomes, healthcare access, patient experience, cost, and value. A review of how the Commonwealth Fund and other similar organizations determine these rankings is provided elsewhere.[8] The American public has approved a healthcare system that incentivizes new, often unproven, technologies; promotes defensive medicine; and limits healthcare insurance for individuals younger than 65 to employment-related options. A detailed examination of additional reasons why American health care lags behind other developed nations is beyond the scope of this activity.

In the 1960s, following Deming and Codman's lead, Avedis Donabedian began advocating that healthcare quality managers should quantify healthcare processes and structures in addition to outcomes.[5] Specifically, Donabedian proposed that healthcare quality managers should measure the following:

- Behaviors and task completion, such as the rate of healthcare provider compliance with checklists and the time healthcare providers spend on specific tasks.

- Infrastructure items, such as the number of computers available in patient rooms and the number of defective syringes encountered, and patient disease state outcomes, such as morbidity and mortality.

He wrote that Most quality studies suffer from having adopted too narrow a definition of quality. They generally concern themselves with the technical management of illness and pay little attention to prevention, rehabilitation, coordination, and continuity of care or handling the patient-physician relationship.

By emphasizing this broader perspective, Donabedian urged healthcare providers and healthcare quality managers to investigate numerous healthcare delivery processes besides healthcare provider technical proficiency to identify areas where process improvements could enhance quality. Since his work, the assessment of healthcare quality has often been separated into 3 primary domains as follows:

- Structure: The resources required to supply health care, including human and inanimate physical resources. Structure measurements evaluate the baseline resource commitments that determine whether a healthcare entity is equipped to offer specific services and the speed at which those services can be delivered.

- Process: The methods, behaviors, and strategies used in healthcare delivery. Process measurements are often binary measures—Was the process completed correctly? Yes or No.

- Outcome: The measurable results of healthcare interventions. Outcome measures are typically assessed as rates. Evaluating the quality of an outcome based on a limited number of results is a poor management strategy unless the result indicates a catastrophic failure.

Health care in the setting of individuals with acute myocardial infarction is discussed as an example.

- Structural measures include as follows:

- How well is an emergency department staffed with healthcare providers who are acquainted with the diagnosis and initial management of acute myocardial infarction?

- How well is a catheterization laboratory staffed with healthcare providers and equipment capable of providing diagnostic and interventional services?

- Process measures include the actions that facilitate the timely transfer of a patient for coronary artery catheterization. A key metric used to assess efficiency is door-to-wire time, which measures the interval from when a patient arrives at the hospital to when a cardiologist crosses the blocked coronary artery with a wire during catheterization. The process can be measured in smaller divisions of the overall process. In the United States, a door-to-wire time of 90 minutes or less has been recommended as a standard.[9]

- Outcomes, the actual results of care, can be measured in many ways, such as follows:

- The success rate of opening coronary artery occlusions

- The average improvement of cardiac function measured by cardiac output

- The 24-hour death rate (the number of patients with acute myocardial infarction who die within 24 hours divided by the total number of patients with acute myocardial infarction treated)

Many healthcare organizations, including the Commonwealth Fund, the Leapfrog Group, and the National Institute of Standards and Technology, have implemented Donabedian's advice to collect such data. Government employees monitor reports from these groups and, in response, regulate facets of healthcare delivery.

Obligating Quality From Healthcare Providers

Obligations to provide quality (and value) to patient-customers stem from a hierarchy of standards, listed in subjective order of binding authority as follows:

- Legal standards for healthcare services and billing include statutes passed by legislatures, executive orders declared by the President and governors, and common laws issued by judges, discussed elsewhere.[2]

- National medical organization standards for healthcare services, including medical societies and organizations that monitor healthcare facilities, such as TJC, are discussed below.

- Local, such as hospital-level policy standards for healthcare services and billing, are discussed below.

- Other ethical norms, such as heuristics for ethical decision-making proposed by Beauchamp and Childress or Jonsen, Siegler, and Winslade, are discussed elsewhere.[1]

The Setting of Healthcare Quality Standards

In the United States, national legal standards are set by the federal legislature, the federal courts, the President and the President's executive branch appointees, and organizations that report to these entities, primarily the Executive Branch.

Since 1953, the United States Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) has been led by an official who reports directly to the President as a Cabinet member. The DHHS is the executive branch department responsible for the portion of American healthcare that is federally controlled (much of American health care is not federally regulated). The DHHS consists of numerous appointed officers (such as the surgeon general) and 11 operating divisions, which include the Food and Drug Administration, the Centers for Disease Control, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The AHRQ, which also interacts with the United States Congress, oversees a network of Patient Safety Organizations (PSOs) and the Network of Patient Safety Databases (NPSD). The AHRQ funds the United States Preventive Services Task Force, created in 1984, to recommend for or against certain medical examinations and treatments depending on whether there is evidence that they are cost-effective for improving health outcomes.

The United States Congress creates healthcare laws under the leadership of (1) the Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee in the Senate and (2) the Ways and Means Committee in the House of Representatives. Congress typically creates laws intended to improve healthcare quality in response to reports by other organizations (discussed further below).

The United States federal court system has made several decisions that have established national healthcare law, including decisions legalizing the withdrawal of life-sustaining care, physician-assisted suicide, and first-trimester abortions if previously legalized by state statute. The federal court system's standard for evaluating healthcare quality is based mainly on the language of pre-existing legislative and judicial law or precedent. Of the 3 branches of government, the federal court system has the least impact on creating healthcare quality using the concepts of quality promoted by Shewhart, Deming, and Donabedian.

The United States executive and legislative branches interact with multiple independent, nonprofit organizations when making policies on healthcare standards. Two examples of such organizations are the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) and the National Quality Forum (NQF).

The NCQA was founded by Margaret O'Kane in 1990 to publish evidence-based quality standards. The organization has since become the primary voluntary quality accreditation program for individual clinicians, health plans, medical groups, and healthcare software companies. The NCQA's primary contributions include maintaining the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) and the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers Systems (CAHPS) survey data. Health insurance plans achieve accreditation by meeting the HEDIS criteria. The NCQA and AHRQ have developed CAHPS surveys for clinicians, hospitals, nursing homes, long-term care facilities, home health facilities, and dialysis centers.

In 2002, CMS, in collaboration with the Hospital Quality Alliance, introduced the hospital CAHPS, now commonly known as Hospital Compare. Health insurance plans, including CMS' Medicare plan—the largest American health insurance plan—use the CAHPS surveys to obtain patient feedback on healthcare services. Insurance plans can impose financial penalties on healthcare organizations with low scores. Scores from certain CAHPS surveys are publicly available for consumers to use when choosing one healthcare organization or healthcare provider over another.

The NQF is a nonprofit membership organization established in 1999. This organization comprises over 400 for-profit and nonprofit organizations that collect data and endorse healthcare standards. Rather than creating its own standards, the NQF primarily endorses standards set by other organizations, increasing legitimacy as a national standard. Membership organizations include consumers, health plans, medical professionals, employers, government, public health, pharmaceutical, and medical device organizations. The NQF typically adopts the guidelines set by national medical societies, such as the American Association of Family Medicine or the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

Regulation of Quality in Hospitals and Other Healthcare Organizations

Healthcare organizations must undergo periodic reviews and submit data to demonstrate that healthcare providers meet quality standards to bill federal and state health insurance programs for services. Federal agents can deem healthcare organizations to have met quality standards through direct investigation. However, federal and state governments more commonly allow independent agencies that set quality standards, such as Det Norsk Veritas, the Healthcare Facilities Accreditation Program, and TJC, to act on their behalf to create and oversee healthcare organization quality of care standards.

Given the complexity of this topic, this activity focuses on the largest of these 3 sets of standards from TJC and does not discuss the nuances of nonuniformity in the standards created by TJC, the other independent accrediting bodies, and the federal government. TJC publishes standards for healthcare providers in its Patient Safety System guidelines, which were last updated in January 2025. According to TJC, each accredited healthcare organization must:

- Ensure its leaders create and maintain a culture of safety and quality throughout the organization.

- Function as a learning organization, requiring continuous education and improvement among personnel.

- Encourage blame-free reporting of system and process failures and encourage proactive risk assessments by healthcare quality managers.

- Report certain adverse events, close calls, and hazardous conditions to TJC.

- Have an organization-wide patient safety program that includes performance improvement activities.

- Collect data to monitor quality performance.

- Hold individuals accountable for their responsibilities. On this point, TJC states that a fair and just culture holds individuals accountable for their actions but does not punish individuals for issues attributed to flawed systems or processes.

Ironically, TJC does not consistently enforce accountability for itself or the hospitals it accredits. Instead, it grants healthcare organizations significant flexibility in interpreting its standards. As a result, 1 TJC-accredited healthcare organization may interpret a standard differently than another, and 2 healthcare organizations may use different standards. Furthermore, if a patient or a clinician has a complaint against a TJC-accredited institution, TJC may refuse to act upon the complaint if the TJC-accredited institution has made a minimum effort to adopt any standard. More than 20% of United States hospitals do not report to TJC or follow its standards. Auditing is important because healthcare organization executives, managers, and providers often do not comply with regulations.[10][11]

Regulation and Setting of Quality Standards

Individual state medical boards and court systems uphold standards for healthcare providers. Medical boards primarily enforce healthcare provider ethics standards, and courts judge issues of healthcare provider negligence in accordance with state laws.

Most healthcare practice quality standards are not established through the regulatory processes described above but are determined by guidelines from national medical specialty organizations. There is considerable overlap in this process. For example, American organizations that publish practice standards in vascular medicine include the following:

- Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS)

- American Venous Forum (AVF) (the SVS and AVF work in conjunction with the ACS)

- Society of Interventional Radiology (an organization that coordinates with the American College of Radiology)

- American College of Cardiology

These organizations may collaborate to develop a unified set of quality guidelines on certain topics. In contrast, some facets of vascular medicine quality may be addressed by none or only one of these organizations.

Although not regulated per se, the federal government and private insurance companies incentivize healthcare providers to meet quality measures through pay-for-performance (P4P) programs that reduce the reimbursement of healthcare providers who do not meet certain quality thresholds. The CMS's current iteration of P4P is the Quality Payment Program (QPP). Most healthcare providers who bill CMS for services receive payment tied to their performance in the QPP's Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), which is one of two payment programs under the QPP. MIPS redistributes payments from healthcare providers who do not meet the criteria to healthcare providers who do meet the criteria, which are extensive and are listed on the QPP website. These requirements involve many types of structures, processes, and outcomes. Over time, CMS has provided healthcare providers more flexibility in meeting quality measures while increasing the overall requirements. Since CMS started healthcare provider P4P in 2006, it has increased the percentage of the revenue tied to P4P criteria that healthcare providers earn from treating Medicare patients to as high as 10% (now at 9%). CMS and private insurance companies also reimburse hospitals and other healthcare facilities using measures related to quality (P4P).

Healthcare Quality Management and Healthcare Quality Managers Standards

The authority to establish standards in healthcare quality management is less defined and more fragmented than that for determining standards in medical ethics and medical and surgical practices. A problem with American healthcare quality management is that healthcare quality managers are often not held to standards themselves. Healthcare providers with training in healthcare quality management comprise a tiny fraction of healthcare providers, including those who establish standards of care guidelines in the national societies listed above. Several quality management organizations directly impacting American healthcare quality management are listed below.

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) is an independent nonprofit organization and PSO started in 1991 by Donald Berwick, a pediatrician who worked as a lead CMS administrator under President Barack Obama. The IHI is an educational and advocacy organization and published its Framework for Clinical Excellence in 2017.

The National Association for Healthcare Quality (NAHQ) is an independent nonprofit organization established in 1976. NAHQ is the only organization offering accredited examinations and certifications for healthcare quality management professionals.

The American Health Quality Association is a nonprofit organization established in 1984 that advocates for healthcare quality management standards and encourages participation from third-party healthcare organizations. However, it does not publish standards or guidelines.

The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) is an independent nonprofit membership organization established in 1918 that primarily endorses quality standards in technology, including health information technology. ANSI formally serves as an American member of the International Standards Organization, which publishes standards for technology-centered businesses and is headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland.

For healthcare quality management to advance like quality management in other industries and for the United States to align with other countries to achieve Donabedian's goals in health care, individuals and organizations that have might (as in might makes right) must set higher-level standards for healthcare quality managers as follows:

- TJC policy writers could mandate that hospitals conduct certain numbers or types of PDSA cycles to maintain accreditation.

- Healthcare organization executives could require their managers to conduct certain numbers or types of PDSA cycles.

- Government officials could require healthcare managers to demonstrate knowledge and skills through examination to receive certification in quality management, similar to certification processes in many healthcare professions.

Terms In Quality Delivery

Quality management has its own terms. Some of these are derived from Japan, where Deming and others enabled Japanese companies to manufacture goods and services, such as cars and electronic devices, of higher quality than those produced in the United States after World War II. Many quality management terms relate to applied statistics, including:

- Continuous data (also known as variables or quantitative data) versus categorical data (also known as attributes or qualitative data)

- Gaussian data distribution versus Poisson, polynomial, or skewed data distributions

- Relative and absolute risk

- Effect size and confidence interval

However, this activity focuses on management concepts and techniques that do not require a background in statistics. Readers interested in more advanced statistical aspects of quality management are encouraged to consult specialized texts.

Analysis of Causes (Independent Variables) Retrospectively

Quality managers analyze all steps in a process to find kaizen ("opportunities for improvement"). When doing so, they often create lists and charts, several of which are briefly described below.

Suppler-input-process-output customer (SIPOC) charts, also known as COPIS, divide a process into 5 components. This structured approach helps determine how to enhance quality based on customer expectations.

Gap analysis identifies specific barriers in a process that can be removed, and it examines why current outcomes differ from desired outcomes. During gap analyses, individuals often communicate using a flow chart.

Flow charts illustrate how individual processes affect a larger overall process. These charts can evaluate which subprocesses should be improved to prevent errors and outcome variability or should be eliminated to reduce waste.

A fishbone diagram, also called an Ishikawa diagram after its inventor, is a flow chart designed to improve the analysis of causes and effects. Instead of depicting a complex process as a linear sequence of factors or steps, a fishbone diagram groups contributing factors into broader categories for more precise analysis.

The classification of causes dates back to Aristotle's books Metaphysics and Physics. Aristotle classified the causes of a thing or outcome into the following components:

- Efficient cause (its maker)

- Final cause (its teleological purpose)

- Formal cause (its design)

- Material cause (its substance)

Modern attempts at classifying causes include alliterations as follows:

- Patron/patient, people at work, provisions, place, and procedures

- Methods, men, machines, and materials

Causes of problems can be (1) anticipated or (2) reacted to; different quality management techniques, such as failure modes effects analysis and root cause analysis (RCA), are available for anticipation or reaction, respectively.

Failure modes effects analysis presents a complex process in the form of a flow chart or table, divided into individual subprocesses, and clarifies how often each subprocess is likely to encounter difficulties. The analysis then explains the various ways these subprocesses can fail and evaluates how easily a minor issue in a process can be detected before it leads to a serious adverse outcome. To improve the overall process and outcomes, quality managers should prioritize correcting subprocesses that frequently fail, are easy to fix, and are challenging to detect.

RCA, also called Root Cause Analysis and Action, works backward from an outcome—typically an unwanted outcome but can be the desired outcome—to its root causes, stopping short of reaching the unmoved mover postulated by Aristotle in Metaphysics. In healthcare organizations, RCAs typically occur as meetings involving all individuals identified as having a role in the processes that led to the outcome. The primary objective of RCA is to identify discrepancies between expected and actual processes, outcomes, and structures. RCA can be facilitated using Ohno and Sakichi Toyoda's 5 Why's Technique and James Reason's Swiss cheese model.[12] In 2015, the National Patient Safety Foundation, which merged with the IHI in 2017, published guidelines on when and how RCA should be performed in the medical setting. CMS thereafter published instructions on its website for healthcare providers on performing RCAs. TJC requires accredited healthcare organizations to perform RCAs whenever any of the 24 defined types of adverse events, called sentinel events, occur.

The techniques discussed thus far do not require data, but incorporating data can enhance objectivity in process and outcome analysis. Healthcare quality managers typically capture data using electronic health record systems or by having healthcare providers document processes using checksheets or checklists, which can be converted into checksheets and uploaded into the electronic health record as needed.

The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group provides the most comprehensive method for ranking levels of evidence. GRADE level 1 evidence indicates that a research design meets certain criteria, ensuring that the identified cause-and-effect relationship is likely to reflect the true relationship if the research were replicated. Such evidence typically requires randomization and control for confounding variables or a meta-analysis of high-quality trials. GRADE emphasizes that data evaluation based on meta-analyses may be no better than analysis of isolated studies. In addition, unlike other evidence ranking systems, GRADE does not consider experts' opinions to qualify as evidence.

Although quality managers should make decisions based on the relative quality of evidence available, it is not feasible for quality managers to perform randomized controlled trials or cross-sectional studies in most circumstances. Instead, they use more straightforward tools to detect trends and relationships between independent and dependent variables when data are available in day-to-day practice, such as histograms or other bar charts and scatter diagrams. For categorical data, a Pareto chart—a type of bar chart—can show which categories contribute relatively more or less to the cause of a desired or undesired outcome. Categorical and continuous data can be analyzed retrospectively and in real-time, enabling faster evidence-based decision-making, which is essential in the healthcare industry where patient-customers' lives are at stake.

Analysis of Processes In Real-Time To Detect And Modify Causes (Independent Variables)

Processes can be monitored in real-time or near-real-time by comparing outcomes between 2 groups—control and experimental groups—or by assessing outcomes in 1 group before and after an intervention. Data can be presented in a table format or by plotting the input or output variables over time in various line charts, particularly run and statistical process control charts.

A run chart is a type of line chart that enables the collected data points to be compared to a measure of the data's central tendency (typically the mean) up to the most recent data point collected. Quality managers use run charts to evaluate fluctuations in categorical or continuous data (typically the latter). Run charts enable the quick detection of process deviations from past trends, allowing for timely corrective action if the new trend is undesirable. These charts also help assess whether a quality manager's recent corrective measures have effectively altered the process.

Shewhart developed a more precise method for calculating and displaying trend deviations from their measure of central tendency once sufficient data had been collected to enable statistical analysis. This method is now referred to as statistical process control, including statistical process control charts, control charts, or Shewhart charts. Statistical process control is the method most commonly used by quality managers to make data-driven decisions about processes at their institution with a degree of statistical certainty. Given its significance, further attention is given to statistical process control, although the specific steps for integrating statistical process control into healthcare quality management are not discussed here.

Statistical process control charts provide a threshold of statistical certainty for identifying when data points deviate from the measure of central tendency by revealing upper or lower limits of what can be expected from the process based on its past results. These thresholds are called control limits or process limits. When an upper or lower threshold is breached, healthcare quality management should search for a new disruptive independent variable that has affected the process through unique cause variation. In contrast, a process variance that does not exceed the threshold should be considered a result of prior fluctuations in the already established independent variables and is termed random variation or common cause variation. Data analysis with statistical process control charts enables decision-making through a level of evidence equivalent to that of a nonrandomized, nonmatched prospective cohort study.

Relative risks and effect sizes can be determined with limits on their reliability due to biases and/or confounding variables. In a stable population of patient-customers, such as those who undergo return visits to a clinic (for example, patients with peripheral arterial disease returning for medical or other rehabilitative noninvasive therapies), data can be obtained pre- and post-intervention on the same patient-customers. This situation also allows for a crossover study design with patient-customers acting as their true controls without interrupting the clinic's operation. The primary goal of healthcare quality management is to implement evidence-based interventions to improve outcomes rather than achieve absolute statistical certainty, analyzing internal organizational data using statistical process control charts can effectively support this objective in most cases.

Statistical process control requires selecting the most appropriate chart format from various options. Each chart type is designated for specific use depending on the characteristics of the data, affecting the type of the most appropriate statistical analysis. Statistical process control charts used in healthcare quality management typically incorporate the standard deviation of the data and compare values to those expected in a Gaussian distribution (a bell curve).[13] Determining how the actual data distribution differs from a Gaussian distribution can be a relevant step in the analysis, potentially indicating the need for a non-standard statistical process control chart. However, customarily used statistical process control charts can typically detect nonrandom process outcomes without the chart creator needing to verify that assumptions of models based on Gaussian statistics are met. Statistical process control is also more effective with one or more process problems and when data collection methods about the problem(s) have already been established/identified. When a process problem or the cause(s) of a problem is not known, healthcare quality management should instead use flow charts, Pareto charts, probability plots, scatter diagrams, histograms, or affinity diagrams to guide initial quality improvement measures.

In summary, healthcare quality managers are expected to do the following:

- Collect data on all possibly relevant independent variables pertaining to the processes for which they are responsible for maintaining quality amenable to statistical analysis.

- Perform statistical analysis using confidence levels and confidence intervals.

- Monitor all recurring processes where corrective managerial actions are time-sensitive by performing run charts.

- Switch from run charts to statistical process control charts for processes that meet the theoretical criteria for appropriately interpreting the statistical process control chart.

Of the many goals that healthcare quality managers should have, the closing discussion is centered around 4 goals, which include the following:

- Achieving uniformity

- Increasing efficiency

- Preserving patient safety

- Focusing service whenever ethically possible on the desires of those being served, such as respecting patient-customers

Achieving Uniformity In Desired Results

Efficacy (accuracy) is the ability of an intervention to achieve the desired results; reliability is the ability of an intervention to achieve results (desired or undesired) consistently. When a threshold level of desired results is based on a reference standard, the reference standard is a benchmark. The term benchmark derives from a technique used by geographic surveyors, which involves basing new results/measurements on a reliable starting point. A benchmark can be derived from any organization that has achieved the desired level of reliability. Organizations that collect data on achieving benchmarks may offer it for free public use, such as CMS on its Hospital Compare website, or for a price, such as the Milliman company.

Uniformity in providing healthcare services and products indicates that each patient-customer receives the best possible service or product under routine circumstances. Such uniformity also enables healthcare providers to fulfill the ethical obligation of distributive justice described by Beauchamp and Childress and as specified by laws, such as the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act of 1986 and the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

In the 1980s, while working at Motorola, engineer Bill Smith promoted using PDSA cycles and statistical process control charts to minimize variability in telecommunications products and services. Smith's goal was to achieve <3.4 defects per million iterations of a process, which means that a defect occurs with a probability distributed at least 6 SD (six sigma) from the mean of a Gaussian distribution. Uniformity in healthcare quality management is partly achievable by following standards of practice published by medical specialty organizations. Healthcare quality managers attempting to fine-tune processes to reach benchmarked outcomes reliably can use run charts to identify causes of process progression toward or away from achieving the benchmark.

However, Deming defined quality as allowing for the tailoring of services to the customer. Furthermore, biological organisms (patients) (1) do not respond as uniformly to interventions as many inanimate objects do, and (2) have different preferences on how they wish to be treated. Thus, services and outcomes for patient-customers must be tailored to a greater degree to allow for nonuniformity, and healthcare quality managers should not expect to reach an error rate of less than six sigma. Healthcare quality managers who wish to achieve accurate, ethical, and just decisions must consider factors that affect quality measurements for healthcare providers. For example, data analysis must account for confounding variables that increase the likelihood of adverse outcomes or that lead to differences in decisions made for one patient-customer versus another. Measures of healthcare provider quality should also be based not only on performance metrics that vary depending on differences in input variables but also on attaining uniform credentials, such as maintenance of board certification and other measures of competence.

Reduction of Waste/Improving Efficiency

An area in which American healthcare quality lags behind other first-world countries is minimizing waste. The Commonwealth Fund reported in 2017 that the United States ranked 10th out of 11 first-world countries on the metric—Doctors ordered a medical test that the patient felt was unnecessary because the test had already been done (recently). If healthcare providers require patient-customers to undergo repeat medical tests when the customer (or an independent quality auditor) has not agreed that repeating the test is valuable to the customer, then Deming's definition of quality is not fulfilled. In 2012, Berwick identified 6 categories of healthcare waste as follows:

- Overtreatment

- Failures of care coordination

- Failures in the execution of care processes

- Administrative complexity

- Pricing failures

- Fraud and abuse

Berwick reported that a conservative estimate of the cost of these practices in the United States exceeds 20% of total healthcare expenditures, noting that the actual total may be far significantly higher. He reported that such inefficiencies cost United States taxpayers tens to hundreds of billions of dollars annually.[14]

Different quality manager experts categorize waste differently. One classification scheme to categorize waste is the 7-point Lean classification devised by Ohno, or its modification to 8 points, 6 of which are excesses and 2 of which are insufficiencies, memorable by the mnemonic TIM U WOOD as follows:

- T: Excess transportation

- I: Excess inventory

- M: Excess motion

- U: Underuse of talent

- W: Excess (wasted) time

- O: Excess processing/over-perfecting

- O: Excess production/overproduction

- D: Underperformance/defective action

Regardless of how waste is categorized, each category serves as a potential area of investigation for healthcare quality managers to improve. Several of the above-listed categories are discussed briefly here.

Overtreatment is a common problem. Clinicians are financially incentivized to recommend doing something over doing nothing. Certain common medical tests have not been shown to improve patient outcomes. Many invasive procedures have not been shown to outperform less invasive therapies. Healthcare providers often deliver services to patients who may not genuinely desire them but accept them due to external pressure from healthcare providers. These services may offer short-term benefits that fail to outweigh long-term costs. In addition, providers may avoid surveillance even when it achieves outcomes that are just as good or better as a given invasive therapy.

Wasted time is a common issue in healthcare, often resulting from service bottlenecks or delays in testing and treatment for patient-customers. Healthcare quality managers can improve service times and inventory supply and demand by borrowing methods from many other industries that outperform health care in time minimization for customers. Examples include using kanban ("billboard") techniques, such as airline traffic controllers and Gantt charts, to reduce incoordination and duplication of efforts among healthcare providers working on the same project.

Human factors engineering can reduce various forms of waste, including motion, time, talent, and defects. Human factors engineering strategies tailor job tasks to match the ability of the person performing them better to make tasks as easy as possible and poka-yoke ("mistake-proof"). An example of this in vascular medicine is designing coaxial sheaths, dilators, catheters, guidewires, and stopcocks in a single system that has seamless interchangeability of items without the ability for healthcare providers to connect or interchange the tools improperly.[15]

Clinical Significance

Healthcare quality management is often problematic because (1) legal and ethical responsibilities for patient care and (2) management decisions are often performed by different individuals without communication, and there are often conflicts of interest concerning these decisions.[16] Healthcare quality managers who are not simultaneously healthcare providers are incentivized to increase efficiency and reduce cost. However, increased efficiency in health care does not equate to increased effectiveness. As discussed in the Defining Quality section above, quality and value depend on patient-customer outcomes. Any healthcare quality management that compromises service features essential for preserving person-centered care or patient-customer safety in the name of efficiency or cost reduction risks the customers' health and potentially worsens the quality and value of the service.

Safety and Safety Culture

The United States executive and legislative branches update laws designed to improve patient safety, such as the Healthcare Research and Quality Act of 1999. This act led to a report called To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System published by the United States Institute of Medicine, now called the National Academy of Medicine.[17] This report highlighted that safety errors result in hundreds of thousands of deaths annually in the United States. The Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act of 2005 established the NPSD. In 2007, the AHRQ developed Healthcare Safety Indicators. In 2008, CMS began penalizing healthcare organizations for allowing some outcomes listed by the NQF to be events that should never happen. This list included 29 events in its 2011 update and is currently under revision. CMS uses the NQF's list of never events as denial for services paid for some of the events. Numerous other organizations promote safety standards, such as TJC, which publishes a list called the National Patient Safety Goals that change yearly.

Despite the increasing number of mandates and penalties imposed by governmental and non-governmental organizations to improve healthcare quality outcomes in the 21st century—along with greater access to information, data, and technology—healthcare provider safety errors were still estimated to comprise the third leading cause of death in the United States as of 2018.[18] Despite TJC's 2017 mandate for healthcare organization managers to establish a culture of safety in their healthcare organization and despite healthcare organization managers advertising that they and the people in their organizations have done so, the medical error data serves as strong evidence that healthcare organizations often still lack a culture of safety, which overlaps with the concept of a just culture. According to TJC, in such a culture, all healthcare providers prioritize patient safety over other business factors, such as the cost and time to complete tasks. According to TJC, healthcare organization employees must be tested on their understanding of safety measures using a validated testing procedure every 18 months. The organization's leaders should promote, reward, and champion behaviors that create such a culture. According to TJC, this includes carrying out a nonpunitive approach to notification and handling of non-reckless safety errors and learning from adverse events, close calls, and unsafe conditions. The NQF also has consensus standards for how healthcare organization leaders, healthcare quality managers, and healthcare providers respond to an adverse event.

Healthcare organizations with such a culture adopt practices and technologies approved/endorsed by the organizations mentioned above and based on the published quality research, particularly level 1 research. The impact of a culture of safety on healthcare organization revenue is hard to quantify, but it can result in cost savings for healthcare organizations. For example, employees at such healthcare organizations tend to have high job satisfaction and low turnover, and patient-customers tend to return for business and not file suits or complaints that lead to fines.

For every suitable process, healthcare quality managers should incorporate (1) poka-yoke ("mistake-proofing") measures and (2) red rules, which are rules that must always be followed and can be used by any employee to stop a patient care process that is not being performed according to pre-established standard procedure. As demonstrated in the Toyota Production System, employees who perform the tasks are often the best at identifying system features that result in errors and, by extension, hazards to patient safety.

Patient-Customer-Centered Care

From an ethical, legal, and business perspective, patient-customer needs should take precedence over the needs of all other stakeholders in the healthcare process. In real life, however, when there is a conflict in goals between the patient-customer and the business or healthcare provider, healthcare organization managers often deprioritize patient-customer goals. Healthcare organization managers and healthcare providers can best serve patient-customers by understanding their objectives, aligning business goals with those objectives when ethically and legally appropriate, and activating them.[19] The term activating has entered management lingo to enable customers to manage their service transactions, such as self-check-in options for airline reservations. This approach is achieved by enhancing their knowledge, skills, and options for self-management of services. Activated patients have been found to achieve better clinical outcomes compared to patients with similar characteristics who were not activated.[20][21]

Empowering patient-customers to make independent decisions, either alone or with their trusted network of family and friends, generally leads to outcomes and satisfaction levels that are equal to or better than those resulting from paternalistic approaches that limit patient choices. A Cochrane Database systematic review of 115 controlled studies representing 34,444 research participants reported that providing patients with decision support tools achieves the following:

- Improves patients' knowledge regarding their medical care options

- Improves the accuracy of their perception of possible benefits and harms

- Increases the degree to which they engage in decision-making

- Reduces healthcare provider-patient decision conflicts

- Increases the likelihood that patients choose treatments that are consistent with their values [22]

The list of methods for improving patient-customer-centered care is lengthy. According to data on Statista.com, approximately 90% of individuals in the United States use smartphones. Therefore, an effective approach to enhancing patient-customer-centered care is through digitized communication tools, such as:

- An encrypted electronic patient portal allowing:

- Access all or portions of their medical records

- View and share medical images bi-directionally

- Schedule appointments based on current availability. A nurse or other healthcare provider can then approve or modify them through a traditional triage system.

- Initiate communication with their healthcare provider at any time, which can then be reviewed on the healthcare provider's own timeline.

- Internet links to freely available pertinent medical literature that patients can review before, during, or after their in-person or virtual visit for healthcare services, including:

- Patient or practitioner-level information produced by national medical societies

- Videos explaining diagnostic and treatment options

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The Responsibility of Teams in Improving System Quality

Successful healthcare continuity depends on effective communication. In 2014, TJC reported that it was made aware of 2378 sentinel events in the United States and divided those events into categories of causes. The top 3 categories included:

- Errors attributed to individuals, excluding leadership-related mistakes (547)

- Errors attributed to leadership mistakes (517)

- Communication errors not otherwise specified (489)

Despite these categorizations, TJC, many other organizations, and quality profession experts have taught that the root cause of most business problems is usually the inadequacy of a process, team, or system, not primarily the inadequacy of an individual. Just as logic exists for attributing poor business practices and outcomes to corporations and not just individuals, it exists for attributing poor healthcare services (acts of commission or omission) and outcomes to teams and systems, not just to individual healthcare providers.

Regarding corporate liability, jurist Joel Prentiss Bishop wrote that Since a corporation acts by its officers and agents, their purposes, motives, and intent are just as much those of the corporation as are their actions. If, for example, the invisible, intangible essence or air that we term a corporation can level mountains, fill up valleys, lay down iron tracks, and run railroad cars on them, it can intend to do it. It can act therein as viciously as virtuously.[from New Comments on the Criminal Law Upon a New System of Legal Exposition. (1892) § 417, 255–56.]

The likelihood of achieving success in quality improvement can increase with well-functioning multidisciplinary teams, compared to individuals working independently, and the flattening of the organizational hierarchy, compared to administrators and non-administrators working independently. Collaboration can expand the range and depth of expertise applied to a problem. Healthcare quality managers should seek input from service delivery staff members directly. Thus, individuals directly involved with or closest to the performance of the process of concern should always be on the team. Inefficiencies not apparent to one individual or group in the process chain may be raised by others elsewhere. Individuals who recognize inefficiencies but lack the authority to address them can rely on team members with greater decision-making power to implement necessary changes.

The managerial approach behind Lean, as used by the Toyota company, emphasizes the following:

- Hoshin ("direction"): Managers introduce changes only after having received input from the lowest-ranked employees and

- Gemba ("actual place"): Managers make decisions based on direct contact or observation with the process and not third-party reports discussed in conference rooms. By empowering their employees, managers maximize the organization's quality improvement potential.

Reaching Consensus And Prioritizing Quality Improvement Efforts

Quality improvement teams should always analyze data. Disagreements regarding the best courses of action are inevitable because of differences in bias, even in the presence of data. In addition to standard voting techniques, modified voting techniques promote a course of action that can be most acceptable in a utilitarian manner. Reaching consensus through these techniques improves teamwork and team member engagement more than decision-making strategies based on the majority rules or might makes right philosophies. Relevant techniques include the following:

- The nominal group technique combines anonymous brainstorming—where each individual generates ideas independently—with voting. This technique limits discussion, such as back-and-forth debating, and emphasizes moving forward with a decision based on participants' previously held beliefs.

- Multi-voting (multi-round voting) enables a sequential, progressive narrowing of choices. After each round, the options receiving the least votes are removed. Additional rounds of voting are performed until the best option or an acceptable prioritization of options is reached.

- The Delphi method combines multi-voting and nominal group technique, facilitating decision-making by achieving broad consensus among all members. Voting is typically stopped when necessary to maintain all voters' favor regarding a statement without requiring overly specific conclusions backed by unanimous agreement.

Prioritizing choices can be challenging when multiple factors compete for attention. Decision tools designed to enhance objectivity and narrow a list of possible options to one or more choices include weighting by ranking, value stream mapping, and prioritization matrices.

Weighting by ranking is a decision tool having various names and permutations. This tool generally involves deriving a rank or hierarchy of scores (measured or calculated values rather than arbitrary ones) for categories of concern, such as tasks, costs, or other attributes. The choices under consideration that share these features can be compared using their performance in the selected categories in a spreadsheet to determine the best option. For example, choosing a method to inform patients of postoperative appointments may involve a decision of 3 options—sending a letter through regular mail, sending a text message, or calling by telephone. The categories of concern may include cost, time, likelihood of message receipt, and patient-customer satisfaction. The categories can be given importance weights, and the options can be ranked according to their overall score across all categories.

Value stream mapping is a decision tool that uses weighting by ranking and is often displayed as a flow chart. In value stream mapping, subprocesses of a larger overall process are assigned weighted values based on relative levels of importance. These values are combined into a final score, known as a criticality index, which helps determine the most crucial process for focusing efforts and devoting resources. Common components of a criticality index include the frequency of the problem (how often a specific issue arises in a critical path), the severity of the problem (if or when it occurs), and the ease of detection of the problem early on (before it becomes unmanageable).

A prioritization matrix is a decision tool that displays options along multiple axes (for example, X, Y, and Z) of competing interests—such as time versus cost or the interests of upper managers, mid-level managers, and non-management level employees—and plots options or problems according to their importance along each axis. Prioritization matrices are typically drawn in a two-dimensional format in a spreadsheet and assigned scores using weighting by ranking; in this manner, numerous options or categories (more than just 2 or 3) can be prioritized. Healthcare quality managers could prioritize quality improvement projects under non-mutually exclusive categories encompassing improving service, improving safety, reducing cost, and maintaining a competitive edge.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Average Costs to a Managed Care Organization. This control chart shows the average costs to a managed care organization over time. In December 2016, costs escalated to more than 3 standard deviations from the mean. By using this chart, the managers at this organization could have realized with a 99.7% certainty threshold, in near real-time, that there was particular cause variation, meaning that there was a real anomaly increasing the costs that they needed to fix, and not just a random variation in costs.

M Young, MD, CPHQ

References

Young M, Wagner A. Medical Ethics. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30570982]

Olejarczyk JP, Young M. Patient Rights and Ethics. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30855863]

Brand RA. Ernest Amory Codman, MD, 1869-1940. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2009 Nov:467(11):2763-5. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1047-8. Epub 2009 Aug 19 [PubMed PMID: 19690929]

Schreiner S. Ignaz Semmelweis: a victim of harassment? Wiener medizinische Wochenschrift (1946). 2020 Sep:170(11-12):293-302. doi: 10.1007/s10354-020-00738-1. Epub 2020 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 32130558]

Best M, Neuhauser D. W Edwards Deming: father of quality management, patient and composer. Quality & safety in health care. 2005 Aug:14(4):310-2 [PubMed PMID: 16076798]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMcCarthy BD, Ward RE, Young MJ. Dr Deming and primary care internal medicine. Archives of internal medicine. 1994 Feb 28:154(4):381-4 [PubMed PMID: 8117170]

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. 2001:(): [PubMed PMID: 25057539]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSchütte S, Acevedo PNM, Flahault A. Health systems around the world - a comparison of existing health system rankings. Journal of global health. 2018 Jun:8(1):010407. doi: 10.7189/jogh.08.010407. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29564084]

Blankenship JC, Haldis TA, Wood GC, Skelding KA, Scott T, Menapace FJ. Rapid triage and transport of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction for percutaneous coronary intervention in a rural health system. The American journal of cardiology. 2007 Sep 15:100(6):944-8 [PubMed PMID: 17826374]

Gondi S, Beckman AL, Ofoje AA, Hinkes P, McWilliams JM. Early Hospital Compliance With Federal Requirements for Price Transparency. JAMA internal medicine. 2021 Oct 1:181(10):1396-1397. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.2531. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34125138]

Lawrence JR, Lee BS, Fadahunsi AI, Mowery BD. Evaluating Sepsis Bundle Compliance as a Predictor for Patient Outcomes at a Community Hospital: A Retrospective Study. Journal of nursing care quality. 2024 Jul-Sep 01:39(3):252-258. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000767. Epub 2024 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 38470467]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceReason J. The contribution of latent human failures to the breakdown of complex systems. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences. 1990 Apr 12:327(1241):475-84 [PubMed PMID: 1970893]

Thor J, Lundberg J, Ask J, Olsson J, Carli C, Härenstam KP, Brommels M. Application of statistical process control in healthcare improvement: systematic review. Quality & safety in health care. 2007 Oct:16(5):387-99 [PubMed PMID: 17913782]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBerwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012 Apr 11:307(14):1513-6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.362. Epub 2012 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 22419800]

Fleisher J, Barbosa W, Sweeney MM, Oyler SE, Lemen AC, Fazl A, Ko M, Meisel T, Friede N, Dacpano G, Gilbert RM, Di Rocco A, Chodosh J. Interdisciplinary Home Visits for Individuals with Advanced Parkinson's Disease and Related Disorders. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2018 Jul:66(6):1226-1232. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15337. Epub 2018 Apr 2 [PubMed PMID: 29608779]

Thompson R, Paskins Z, Main BG, Pope TM, Chan ECY, Moulton BW, Barry MJ, Braddock CH 3rd. Addressing Conflicts of Interest in Health and Medicine: Current Evidence and Implications for Patient Decision Aid Development. Medical decision making : an international journal of the Society for Medical Decision Making. 2021 Oct:41(7):768-779. doi: 10.1177/0272989X211008881. Epub 2021 May 8 [PubMed PMID: 33966538]

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. 2000:(): [PubMed PMID: 25077248]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMakary MA, Daniel M. Medical error-the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2016 May 3:353():i2139. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2139. Epub 2016 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 27143499]

Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2013 Feb:32(2):207-14. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1061. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23381511]

Fors A, Ekman I, Taft C, Björkelund C, Frid K, Larsson ME, Thorn J, Ulin K, Wolf A, Swedberg K. Person-centred care after acute coronary syndrome, from hospital to primary care - A randomised controlled trial. International journal of cardiology. 2015:187():693-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.336. Epub 2015 Mar 24 [PubMed PMID: 25919754]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePirhonen L, Gyllensten H, Fors A, Bolin K. Modelling the cost-effectiveness of person-centred care for patients with acute coronary syndrome. The European journal of health economics : HEPAC : health economics in prevention and care. 2020 Dec:21(9):1317-1327. doi: 10.1007/s10198-020-01230-8. Epub 2020 Sep 7 [PubMed PMID: 32895879]

Stacey D, Légaré F, Col NF, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, Eden KB, Holmes-Rovner M, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Lyddiatt A, Thomson R, Trevena L, Wu JH. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014 Jan 28:(1):CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub4. Epub 2014 Jan 28 [PubMed PMID: 24470076]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence