Introduction

Blepharitis, a chronic inflammatory disorder of the eyelid margins, is one of the most common eye conditions treated by ophthalmologists and optometrists worldwide, affecting individuals of all ages and ethnicities. The term "blepharitis" encompasses a group of disorders characterized by pain, itching, and redness at the eyelid edges.[1] The condition can be classified based on the affected area and underlying causes. While not typically a threat to vision, chronic blepharitis can significantly impact a patient's quality of life due to its recurrent nature and persistent symptoms, which require long-term management. Secondary ocular complications, such as conjunctivitis, dry eye disease, and, in severe cases, vision loss from superficial keratopathy or corneal neovascularization, can also arise from blepharitis.

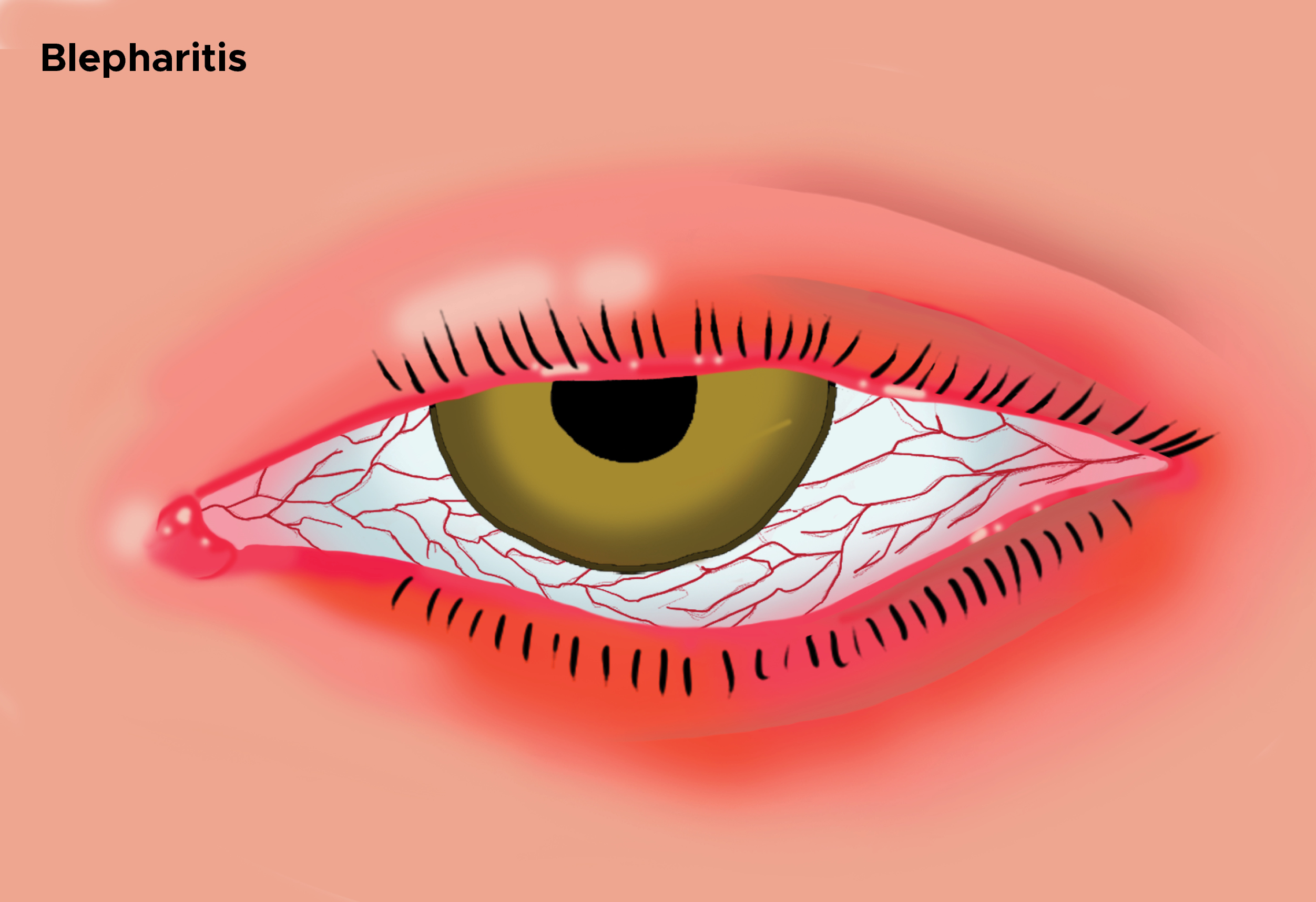

Blepharitis is an ophthalmological condition characterized by inflammation of the eyelid margins.[2] The condition can present as acute or chronic,[3] with the chronic being the more common form (see Image. Illustration of Blepharitis Showing Swollen Eyelid).[4] Blepharitis can be further classified based on its location, which can be anterior or posterior. Symptoms are typically recurrent, may fluctuate over time, and often affect both eyes.

Anterior blepharitis primarily affects the skin around and behind the eyelashes (see Image. Anterior Blepharitis). This condition is commonly associated with seborrheic dermatitis, which is characterized by dry and scaly skin or bacterial infections, particularly those involving Staphylococcus species. In contrast, posterior blepharitis, also known as meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD), affects the meibomian glands at the back of the eyelid. MGD leads to meibomian gland obstruction or aberrant lipid secretion, disrupting the tear film and causing tear instability and evaporation.[5]

A notable feature of blepharitis is the overlap of symptoms and findings between its anterior and posterior forms. Common symptoms, such as burning, itching, redness, and a sensation of a foreign body, often present initially and tend to worsen upon waking. The persistent inflammation of the eyelids causes these symptoms, which can worsen during sleep when blinking is absent. The tear film stagnates overnight, leading to lipid buildup and the production of inflammatory mediators, exacerbating the discomfort. Understanding blepharitis is crucial not only because of the condition itself but also due to its association with other ocular and systemic disorders. For example, rosacea, a systemic dermatological condition, often coexists with posterior blepharitis and leads to inflammatory changes in both the meibomian glands and the skin.[6] Furthermore, seborrheic dermatitis, commonly affecting the scalp and other sebaceous gland-rich areas, is frequently observed in patients with seborrheic blepharitis, highlighting the link between blepharitis and overall dermatological health. The link between blepharitis and various systemic disorders highlights the importance of a holistic approach to treatment and suggests that interdisciplinary intervention may be required for optimal care.

Although blepharitis is common and chronic, long-term management remains challenging. Persistent inflammation in the eyelid area can lead to gland atrophy, thickening of the eyelid margins, and tear film instability, perpetuating a cycle of irritation and inflammation. The establishment of standardized treatment procedures is further complicated by the fact that the pathophysiology of blepharitis involves several pathways that are currently poorly understood.

Adherence to eyelid hygiene and maintenance medications is crucial for symptom management and preventing recurrence. This complexity highlights the need for individualized treatment plans and patient education. The primary treatment for blepharitis includes proper eyelid hygiene and avoiding triggers that worsen symptoms. Topical antibiotics may also be prescribed.[7] Patients who are refractory to these measures should be referred to an ophthalmologist. The goal of treatment is to alleviate symptoms, as most blepharitis is chronic and requires ongoing hygiene maintenance to prevent recurrences. While there is no definitive cure, the prognosis for blepharitis is generally good. Blepharitis is more of a symptomatic condition than a true health threat.[8]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The causes of blepharitis vary depending on whether it is acute or chronic, and, in the case of chronic blepharitis, the location of the problem.[9] Acute blepharitis can be either ulcerative or nonulcerative. Ulcerative blepharitis is typically caused by a bacterial infection, most commonly staphylococcal, but may also result from viral infections such as herpes simplex virus (HSV) or Varicella zoster. Nonulcerative blepharitis is usually an allergic reaction, such as atopic or seasonal allergies. The chronic form of blepharitis is best classified based on its location.

An infection, typically staphylococcal, or a seborrheic process is commonly involved in anterior blepharitis. Individuals with this form of blepharitis often have seborrheic dermatitis on the face and scalp and may also have an association with rosacea. Posterior blepharitis is caused by MGD, where the glands over-secrete an oily substance, leading to clogging and engorgement. This form is frequently linked to acne rosacea, and hormonal factors are also suspected. Both anterior (Demodex folliculorum) and posterior (Demodex brevis) blepharitis may be associated with Demodex mites. However, their exact role remains unclear, as asymptomatic individuals also harbor the mites at similar prevalence rates.[10][11]

Blepharitis has a complex etiology involving bacterial infections, skin disorders, gland dysfunction, and occasionally parasitic invasion. One of the most well-established contributing factors is the presence of bacteria, particularly Staphylococcus species, on the eyelid margin. Studies have shown that blepharitis patients have significantly higher levels of coagulase-negative staphylococci and Staphylococcus aureus on their eyelids compared to healthy individuals.[12] These bacteria exacerbate the inflammatory process by producing toxins that irritate the eyelid surface and disrupt the normal discharge of the meibomian glands. Some bacterial strains also produce the enzyme lipase, which breaks down the lipid components of the tear film, leading to the production of free fatty acids. This can worsen inflammation and destabilize the tear film. A key contributor to the etiology of blepharitis, particularly anterior blepharitis, is seborrheic dermatitis, alongside bacterial involvement.[13] This condition typically affects areas with abundant sebaceous glands, such as the scalp, eyelids, and nasolabial folds.[14] Blepharitis is characterized by flaky skin and excessive sebum production, which promote bacterial growth. The overproduction of sebum can lead to oily crusts and scales along the eyelid edges, potentially harboring bacteria and causing persistent irritation. The systemic nature of seborrheic dermatitis is evident, as patients with seborrheic blepharitis often exhibit symptoms of the condition in other areas. The primary cause of posterior blepharitis is MGD.[15] MGD occurs when the lipid layer of the tear film becomes insufficient due to meibomian gland obstruction or abnormal thickening of glandular secretions. This lipid layer is crucial for maintaining tear film stability and preventing rapid tear evaporation. Dryness, irritation, and inflammation of the ocular surface can indicate tear film instability caused by MGD-related meibomian gland secretion deficiencies. Systemic disorders, such as rosacea,[13] which may cause telangiectasia and hyperemia around the eyelids, are also associated with MGD and can worsen inflammation and gland dysfunction. Demodex mite mite infestation can contribute to blepharitis, particularly in patients with chronic or refractory cases. The 2 mite species—D folliculorum and D brevis—commonly inhabit the sebaceous glands and hair follicles of the human face.[16] Although healthy individuals typically have low levels of these mites, a severe infestation can lead to demodicosis. The mites irritate the eyelid margins, causing inflammation by blocking hair follicles and producing waste particles. A characteristic symptom of Demodex-related blepharitis is cylindrical dandruff-like scaling at the base of the eyelashes, which is closely associated with Demodex infestation. Anti-parasitic treatments aimed at eradicating the mites are commonly used to address this specific cause. The interaction of these etiological factors highlights the complexity of blepharitis. Chronic inflammation along the eyelid margins is often caused by a combination of glandular, bacterial, and dermatological dysfunction. The coexistence of these factors complicates treatment, necessitating a comprehensive approach that addresses each contributing element. Recognizing the distinct role of each factor is essential for developing effective treatment strategies that alleviate symptoms and prevent recurrences in blepharitis patients.

Epidemiology

Blepharitis is not specific to any particular group, affecting individuals of all ages, ethnicities, and genders. Estimates suggest that between 37% and 47% of patients treated by eye care specialists in the United States have blepharitis, making it one of the most common ocular disorders seen in clinical practice.[17] Although blepharitis can affect people of all ages and ethnic backgrounds, its prevalence tends to increase with age, likely due to the impact of the normal aging process on meibomian gland function. The condition is most commonly seen in individuals aged 50 or older.[18]

A major cross-sectional study conducted in Spain highlighted the prevalence of blepharitis, showing that symptomatic and asymptomatic MGD affected approximately 21.9% and 8.6% of the general population, respectively.[19] A 10-year study conducted in South Korea (2004–2013) determined the overall incidence of blepharitis to be 1.1 per 100 person-years. The incidence increased over time and was higher in female patients. The prevalence for individuals aged 40 or older was 8.8%.[20]

The epidemiology of blepharitis also appears to be influenced by gender. Some research suggests that women are more likely to be affected by certain subtypes of blepharitis, including staphylococcal blepharitis. For example, a single-center study found that women, with an average age of 42, comprised most patients with staphylococcal blepharitis.[21] MGD and posterior blepharitis are more commonly observed in older populations, where age-related changes in glandular secretions and gland dysfunction are more prevalent. This condition, which links dermatological disorders with ocular manifestations, is also more frequently seen in populations with a higher incidence of rosacea.

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiology of blepharitis remains unclear but is likely multifactorial. Contributing factors include chronic low-grade bacterial infections of the ocular surface, inflammatory skin conditions such as atopy and seborrhea, and parasitic infestations with Demodex mites. Inflammation, bacterial colonization, and glandular dysfunction intricately interact in the pathophysiology of blepharitis, leading to tear film breakdown and persistent ocular surface discomfort.

Although the 2 main types of blepharitis, anterior and posterior, involve somewhat different underlying mechanisms, they share inflammatory pathways that ultimately result in symptoms that are identical. In anterior blepharitis, the eyelid margin is directly colonized by bacteria, commonly Staphylococcus species. These bacteria release toxins and enzymes, such as lipase, that break down lipids, producing cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory free fatty acids. These fatty acids destabilize the tear film's lipid layer. Prolonged exposure to these free fatty acids can lead to corneal damage in addition to causing discomfort.

Histopathology

Depending on whether blepharitis is anterior or posterior, histopathological changes manifest as specific cellular and structural alterations near the edges of the eyelids. In cases of anterior blepharitis caused by Staphylococcus species, microscopy often reveals infiltration of inflammatory cells, including neutrophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells.[22] The localized immunological response triggered by bacterial colonization is evident from the clustering of inflammatory cells near hair follicles and sebaceous glands. Hyperkeratinization of the eyelid margin, a common feature, contributes to crusting and scaling around the lash bases, which are characteristic of this subtype. Histopathology of seborrheic blepharitis often reveals epidermal hyperplasia with acanthosis, indicating thickening of the epidermis.[22] This condition is frequently accompanied by loose, flaky scales typical of seborrheic dermatitis and an abundance of sebaceous material on the surface. Clinically, oily crusting and greasy skin are commonly associated with enlarged or irritated sebaceous glands. Compared to staphylococcal blepharitis, this subtype generally exhibits fewer inflammatory cells, suggesting a less intense immune response but a stronger correlation with skin disorders such as dandruff. In posterior blepharitis or MGD, the meibomian glands display distinctive histopathological features.[23] Ductal obstruction, glandular atrophy, and acinar dropout, commonly observed in meibomian glands, lead to reduced lipid secretion and altered meibum quality. Over time, fibrosis within the glands may develop, resulting in irreversible structural changes and further disruption of the tear film. Histological examination of patients with chronic MGD may reveal glandular dilatation, thickening of the eyelid margin, and prominent blood vessels.[24] Histopathological analysis of Demodex-associated blepharitis often reveals Demodex mites in the sebaceous glands or hair follicles.[16][25] These mites contribute to local irritation through their waste products and cause mechanical obstruction of the follicles. In response to the mite infestation, surrounding tissues typically exhibit hyperkeratinization and perifollicular inflammation, leading to the characteristic cylindrical dandruff observed clinically. Recognizing this histopathological pattern is essential for accurately diagnosing and treating demodectic blepharitis. Inflammation, hyperkeratinization, and glandular changes are common histopathological features of blepharitis that align with clinical observations. Histological investigation is often used when malignancy is suspected or when structural changes resulting from persistent inflammation resemble neoplastic conditions.[26] By recognizing these microscopic alterations, clinicians can more accurately diagnose blepharitis and determine the most appropriate treatment plan.

History and Physical

A comprehensive physical examination and a complete medical history are essential for accurately diagnosing a patient suspected of having blepharitis. The most common symptoms reported by patients include chronic redness, burning, itching, and a sensation of having a foreign body in the eyes.[27] Prolonged closure of the eyelids during the night can lead to stagnation of the tear film and an accumulation of inflammatory mediators, which often worsens symptoms by morning. Additionally, some individuals may experience light sensitivity or hazy vision, especially if the tear film is significantly damaged.[15]

While taking a patient's history, it is crucial to ask about any systemic illnesses that may be linked to blepharitis, such as rosacea, seborrheic dermatitis, or a history of dry eye disease.[6] Patients should also be inquired about contact lens use, recent eye infections, and any cosmetics worn around the eyes, as these factors can worsen blepharitis. Additionally, patients should be evaluated for posterior blepharitis if they have a history of frequent chalazia or styes, as they may be more susceptible to MGD.[28] During a physical examination, it is essential to closely examine the meibomian glands, eyelashes, and eyelid margins. Collarettes, which are scaling or crusting around the base of the eyelashes, are a common sign of anterior blepharitis and often suggest a staphylococcal infection. More widespread oily scaling along the eyelid margin may be observed in patients with seborrheic blepharitis. This condition is frequently associated with seborrheic dermatitis in other facial areas. Patients with blepharitis commonly report itching, burning, and crusting of the eyelids. Additional symptoms may include tearing, blurred vision, and a sensation of a foreign body in the eyes. Symptoms are generally more pronounced in the morning, with noticeable lash crusting upon waking. Typically affecting both eyes, the symptoms can be intermittent.

The physical examination is most effectively conducted using a slit lamp. In anterior blepharitis, a slit lamp examination often reveals erythema and edema of the eyelid margin, with telangiectasia visible on the outer portion of the eyelid. Scaling at the base of the eyelashes, forming characteristic "collarettes," is often observed (see Image. Slit-Lamp View of Blepharitis With Eyelid Crusting). Additional features may include lash loss (madarosis), lash depigmentation (poliosis), and misdirected lashes (trichiasis). In posterior blepharitis, the meibomian glands frequently appear dilated, obstructed, and capped with oil. Gland secretions may be thickened, and lid scarring is often noted around the glandular region.

The tear film often exhibits rapid evaporation in all types of blepharitis, which can be assessed by measuring tear break-up time (TBUT). During a slit lamp examination, fluorescein dye is applied to the eye. Fluorescein staining may reveal punctate epithelial erosions on the conjunctiva or cornea, indicating damage from persistent inflammation and unstable tear films.[29] Assessing tear osmolarity and measuring TBUT are valuable tools, particularly for distinguishing blepharitis from other ocular surface disorders, such as aqueous tear deficiency.[30]

Differentiating blepharitis subtypes and tailoring treatment strategies require a comprehensive assessment of the patient's medical history and physical examination findings. During the evaluation, the patient is instructed to blink fully and then keep their eyes open for 10 seconds. The tear film is observed for breaks or dry spots under cobalt blue light. A TBUT of less than 10 seconds is typically considered abnormal.

The meibomian gland orifices must be examined to diagnose posterior blepharitis or MGD.[31] Applying mild pressure to the eyelid may reveal turbid or thickened secretions from glands that appear capped, dilated, or obstructed in affected individuals. MGD is often associated with telangiectasia of the eyelid margin, lash misdirection, and rapid tear film break-up time, indicating poor tear stability. Slit-lamp biomicroscopy can aid in identifying tear film abnormalities and subtle inflammatory changes in the conjunctiva and eyelid.

Evaluation

Determining the severity, subtype, and underlying causes of blepharitis requires a combination of clinical observation, patient history, and diagnostic testing. A thorough slit-lamp examination serves as the primary diagnostic method, allowing detailed visualization of the tear film, meibomian glands, and eyelid margins. This examination helps clinicians distinguish the oily scales associated with seborrheic dermatitis from the hallmark features of anterior blepharitis, such as crusting or collarettes at the base of the eyelashes. In posterior blepharitis, the slit-lamp examination may reveal thickened secretions, dilated glands, and capped orifices, indicating MGD. Additional tests may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis in more complex cases or when the initial treatment is ineffective. In cases of recurrent or treatment-resistant anterior blepharitis, conjunctival cultures are occasionally obtained from the eyelid margin to identify bacterial strains or other pathogens.[32] This is particularly helpful when a non-staphylococcal infection, such as molluscum contagiosum, is suspected. When standard management approaches fail, these cultures can guide antibiotic therapy and confirm bacterial involvement.[33] Additional information can be obtained through quantitative assessments of tear osmolarity and stability, particularly in patients with coexisting dry eye disease.[34]

Patients with blepharitis often exhibit decreased tear film stability due to insufficient or altered lipid production by the meibomian glands, commonly assessed using TBUT. Tear film instability is one of the main characteristics of blepharitis-induced dry eye, which is typically indicated by a TBUT of less than 10 seconds. Although not a definitive diagnostic tool for blepharitis, tear osmolarity tests can help differentiate between evaporative and aqueous-deficient dry eye, aiding in the exclusion of other causes of ocular surface irritation.[35] Microscopic analysis of epilated eyelashes is particularly useful when a Demodex infection is suspected. Light microscopy allows clinicians to confirm the presence of mites and observe the characteristic cylindrical dandruff around the base of the eyelashes, a hallmark of Demodex-associated blepharitis.[36] Targeted anti-parasitic medications, typically reserved for patients with significantly exacerbated blepharitis due to Demodex infestations, can help identify cases where this test may be beneficial. A biopsy may be required if structural changes or asymmetry raise concerns about malignancy. Eyelid biopsies are typically reserved for cases of unilateral or atypical blepharitis, where ruling out alternative diagnoses, such as basal cell carcinoma or sebaceous carcinoma, is necessary.[37] As underlying cancers can mimic chronic blepharitis, biopsies are crucial in ensuring early detection of malignancies. Thus, a thorough evaluation is essential to diagnose accurately, differentiate blepharitis from other eyelid conditions, and ensure patients receive optimal care.

Treatment / Management

Eyelid hygiene is the cornerstone of blepharitis treatment and effectively manages most cases.[38] Applying warm, wet compresses to the eyes for 5 to 10 minutes helps soften debris and oils while dilating the meibomian glands. Following this, the eyelid margins should be gently cleansed with a cotton applicator soaked in diluted baby shampoo to remove scales and debris.[39] Care should be taken to avoid using excessive soap, which may lead to dry eyes. Individuals with posterior blepharitis benefit from gently massaging the eyelid margins to express oils from the meibomian glands. This can be performed using a cotton applicator or by rubbing the lid margins with a fingertip in small circular motions. During symptomatic exacerbations of blepharitis, eyelid hygiene should be performed 2 to 4 times daily.

In patients with chronic blepharitis, a daily lid hygiene regimen must be maintained lifelong to prevent the recurrence of irritating symptoms. Additionally, eye makeup should be minimized, and potential triggers should be eliminated. Addressing any underlying conditions that contribute to the condition is important.[40][41] Artificial tears can serve as adjunctive therapy to maintain the tear film and alleviate dry eye symptoms. They are particularly beneficial for patients with severe tear film instability caused by MGD.

Topical antibiotics are recommended for all cases of acute and anterior blepharitis to provide symptomatic relief and eliminate bacteria from the lid margin. Antibiotic creams such as bacitracin or erythromycin can be applied to the lid margin for 2 to 8 weeks.[42] Oral tetracyclines or macrolide antibiotics may be prescribed for posterior blepharitis that does not respond to eyelid hygiene or is associated with rosacea.[43] These oral antibiotics are utilized for their anti-inflammatory and lipid-regulating properties. Short courses of topical steroids can be helpful for patients with ocular inflammation. Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Blepharoconjunctivitis," for more information. Recent trials have shown that antibiotics and corticosteroids can significantly improve symptoms. They are often prescribed as a combination topical treatment for patients who have not responded to eyelid hygiene alone.(A1)

The most common cause of eyelid contact dermatitis associated with blepharitis is frequent rubbing of the eyelids, often due to epiphora and itching. The primary step in management is to prevent touching, rubbing, or wiping the affected eyes. Topical low-dose steroid cream can promote faster healing of the affected skin. Maintaining proper lid hygiene is essential. Antibiotics are ineffective unless there is an infective focus causing blepharitis. Lubrication may worsen epiphora and dermatitis. For posterior blepharitis, lid massage and Betadine lid scrubs can be helpful.

Demodex-associated blepharitis requires treatments specifically targeting the mites. Tea tree oil-based topical treatments are effective against Demodex and are commonly used in lid hygiene routines for individuals with a proven infection.[44] In-office treatments using concentrated tea tree oil or certain anti-parasitic medications could be suggested for more serious infestations. Standard blepharitis treatments do not address mite elimination, making them insufficient for patients with Demodex blepharitis. In these cases, targeted treatment is essential. Tea tree oil eyelid and shampoo scrubs can benefit patients with significant Demodex infestations for at least 6 weeks.[45]

Recent therapies have become available for the treatment of blepharitis. Thermal pulsation therapy, such as the LipiFlow device, applies heat to both the anterior and posterior surfaces of the eyelids.[46] Pulsations gently remove debris and crusting from the meibomian glands. MiBoFlo is another thermal therapy that is applied externally to the eyelids.[47] BlephEx is a rotating light burr used to remove debris from the meibomian gland orifices, promoting better oil flow and enhancing the response to heat therapies.[48] The Maskin probe, a stainless steel instrument applied to an anesthetized meibomian gland orifice,[49] uses a mild electrical current to stimulate oil secretion.[50] While some small trials have shown promise, further clinical research is needed to establish the efficacy of these treatments.(A1)

Patient education is an essential aspect of effectively managing blepharitis. Patients should be informed about the chronic nature of the condition and the importance of adhering to the prescribed treatment plan to prevent recurrences. Patients should also be advised to regularly consult an ophthalmologist to monitor progress and adjust the treatment plan as needed. By combining these therapeutic approaches, most patients can experience significant symptom relief and a reduction in the frequency of exacerbations.

Differential Diagnosis

Differentiating blepharitis from other conditions is essential for ensuring appropriate treatment. Symptoms such as eyelid redness, scaling, and irritation overlap with ocular rosacea, seborrheic dermatitis, and contact dermatitis, making these conditions important differential diagnoses.[51][52] As MGD and eyelid telangiectasia are features shared by both posterior blepharitis and ocular rosacea, differentiation between the 2 conditions is challenging. However, systemic skin manifestations such as papules and facial flushing, which are common in rosacea, can provide valuable diagnostic clues. Scaling may appear around the eyes, eyebrows, and nasolabial folds in seborrheic dermatitis, which often coexists with seborrheic blepharitis.[53] This condition is typically less inflammatory than bacterial blepharitis and responds well to topical steroids and antifungal treatments. A thorough skin examination can help differentiate seborrheic dermatitis from primary blepharitis, particularly when scaling is present in sebaceous-rich areas beyond the eyelids. Blepharitis can also be mistaken for infectious eyelid diseases such as molluscum contagiosum[54] and HSV blepharitis.[55] Patients with HSV blepharitis often have a history of prior herpes infections and may present with painful vesicular lesions on the eyelids. Molluscum contagiosum, typically seen in children or immunocompromised individuals, appears as small, dome-shaped papules along the eyelid margin. Accurate diagnosis is crucial, as these conditions require specific antiviral treatments that differ significantly from those used for blepharitis. Chronic eyelid conditions, such as sebaceous gland carcinoma and meibomian gland carcinoma, are rare but important differential diagnoses, especially in cases of asymmetric or unresponsive blepharitis.[56] These cancers may initially present with eyelid thickening, scaling, and lash loss, which can mimic persistent blepharitis. However, any persistent lesion that does not resolve should raise suspicion for cancer and warrant a biopsy for diagnosis confirmation. Blepharitis can be confused with other inflammatory and autoimmune diseases affecting the eyelid margins, such as cicatricial pemphigoid [57] and atopic dermatitis.[58] Atopic dermatitis often presents with widespread skin involvement, including eczematous changes and chronic skin thickening. In contrast, cicatricial pemphigoid, a rare autoimmune disorder, is distinguished from typical blepharitis by its potential to cause symblepharon and conjunctival scarring. A detailed assessment of systemic symptoms and medical history is essential to differentiate these conditions and determine the appropriate treatment approach.

The differential diagnosis for blepharitis includes:

- Bacterial conjunctivitis

- Bacterial keratitis

- Basal cell carcinoma

- Chalazion

- Contact lens complications

- Dry eye disease

- Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis

- Hordeolum

- Ocular rosacea

- Trichiasis

Prognosis

Blepharitis rarely threatens vision, so the prognosis is generally positive. However, as a chronic and recurrent condition, blepharitis can significantly impact a patient’s quality of life if left untreated or poorly managed. Maintaining proper eyelid hygiene and adhering to prescribed treatments can help most individuals effectively manage symptoms, reducing the frequency and severity of flare-ups. Most patients can maintain functional vision and avoid serious complications with appropriate care. Ongoing management, however, may be necessary to prevent recurrences and sustain long-term symptom control.[59]

When blepharitis is associated with systemic disorders such as rosacea or seborrheic dermatitis, the prognosis may vary depending on how well the underlying condition is managed.[60] For instance, MGD associated with poorly controlled rosacea can lead to more frequent and severe episodes of posterior blepharitis. A comprehensive treatment approach that includes both systemic and ocular therapies can reduce the risk of chronic symptoms and improve the overall prognosis in these cases.[61]

Successful mite eradication and adherence to follow-up therapy are crucial for the prognosis of patients with Demodex-associated blepharitis. To fully eliminate the mites and prevent reinfestation, patients may require targeted treatments for Demodex infestations, which can be challenging to manage. When these treatments are effective, patients often experience significant symptom improvement and a reduced risk of recurrence.[62]

Complications

Blepharitis can lead to various complications, particularly in chronic or poorly managed cases. One of the most common is dry eye syndrome, which results from altered lipid secretion by the meibomian glands, disrupting the tear film.[63] This instability in the tear film worsens dryness, discomfort, and visual fluctuations, potentially diminishing a patient's quality of life. In the context of blepharitis, dry eye disease is typically classified as evaporative dry eye, as the primary cause is the insufficient lipid layer in the tear film. Recurrent chalazia, also known as styes, are inflammatory lumps that form due to infection of the eyelash follicles or blockage of the meibomian glands. Medical or surgical intervention may be necessary if these lesions do not resolve independently.[64] Chalazia can be both painful and cosmetically concerning. They are most common in individuals with posterior blepharitis, and frequent recurrence may lead to secondary scarring and deformity of the eyelids. Severe blepharitis can lead to corneal complications such as corneal ulcers, marginal infiltrates, and punctate epithelial erosions. Without treatment, persistent inflammation and tear film instability can damage the corneal epithelium, potentially resulting in infection or ulceration.[65] Chronic corneal involvement may cause vision impairment due to neovascularization and scarring. Prompt treatment of blepharitis-related corneal issues is essential to prevent these potentially blinding consequences.

Furthermore, chronic blepharitis can lead to structural changes in the eyelid, such as thickening of the lid edge, misdirected eyelashes (trichiasis), and eyelash loss (madarosis).[66] Trichiasis can cause additional ocular surface irritation, leading to corneal abrasions and subsequent infections. Although madarosis does not directly affect vision, it can cause cosmetic concerns and is often difficult to correct once it occurs. These structural changes emphasize the importance of early and consistent treatment to prevent long-term damage to the eyelids. Complications such as corneal involvement, eyelid border scarring, and chronic dry eye are more common in patients with severe or treatment-resistant blepharitis.[67] Patients in this category may require more intensive therapies, such as oral antibiotics or thermal pulsation treatments, as these issues can threaten vision if not addressed promptly.[68] In such cases, the prognosis is more guarded, as long-term changes to the meibomian glands and eyelid structure may lead to persistent symptoms, even with optimal care.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Maintaining daily eyelid cleanliness is essential for managing symptoms and preventing flare-ups, making patient education a key aspect of blepharitis treatment. Patients should be informed about the chronic nature of blepharitis to set realistic expectations and emphasize the need for ongoing therapy. Patients should be educated about the proper technique for eyelid hygiene, which includes using warm compresses, massaging the eyelids, and cleaning them with a mild soap or commercially available eyelid cleanser. Demonstrations and visual aids can enhance patient understanding and ensure they are able to perform these tasks effectively at home. Patients should also be advised on lifestyle changes that can help alleviate symptoms, such as limiting makeup use, reducing exposure to environmental irritants, and cutting back on screen time to prevent digital eye strain. Increasing omega-3 fatty acid intake, which has been shown in some studies to support meibomian gland function, may benefit those with posterior blepharitis. Additionally, patients should be counseled to avoid rubbing their eyes, as this can exacerbate inflammation and damage the tear film.

As the severity of blepharitis is often linked to underlying conditions such as rosacea or seborrheic dermatitis, patient education should also focus on managing these disorders. For individuals with Demodex-related blepharitis, specific guidance on preventing reinfestation is important, such as regularly washing personal belongings and bedding, which can help reduce the risk of recurrence. Educating patients about the potential role of underlying disorders can improve their compliance with therapy and overall outcomes. Providing information about their condition and coping strategies empowers patients, helping them feel more in control of their symptoms and increasing adherence to treatment plans. Healthcare professionals can significantly enhance patient satisfaction and long-term results in the management of blepharitis by emphasizing the importance of consistent eyelid hygiene and follow-up care.

Pearls and Other Issues

Effectively managing blepharitis requires understanding the specific challenges and factors associated with the condition, in addition to addressing its symptoms. An important clinical pearl is the significance of meibomian gland expression in diagnosing and managing posterior blepharitis. Another key factor is the ability to differentiate between anterior and posterior blepharitis. Another important consideration is differentiating between anterior and posterior blepharitis. While these subtypes often coexist, identifying the more prevalent type allows for more targeted treatment, such as focusing on gland function in posterior blepharitis or bacterial eradication in anterior blepharitis. The potential for suboptimal outcomes due to misdiagnosis or a generalized treatment approach highlights the importance of thorough inspection and accurate classification.

While blepharitis is rarely sight-threatening, it can lead to eyelid scarring, excessive tearing, hordeolum and chalazion formation, and chronic conjunctivitis. In severe cases, keratitis and corneal ulcers may develop, potentially resulting in vision loss. Blepharitis is typically a chronic condition marked by periods of exacerbation and remission. While symptoms can often be managed and improved, a complete cure is uncommon. When treating patients with asymmetric or nonresponsive blepharitis, clinicians should also be vigilant for signs of malignancy. Although rare, basal cell carcinoma and sebaceous gland carcinoma can mimic blepharitis, presenting as persistent, unilateral eyelid inflammation. Early biopsies of suspicious lesions can improve prognosis and help prevent delayed diagnosis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Blepharitis is characterized by inflammation of the eyelid margins, which can be either acute or chronic. The primary treatment involves maintaining good eyelid hygiene and eliminating triggers that exacerbate symptoms. Topical antibiotics may be prescribed as part of the treatment. Patients who do not respond to these measures should be referred to an ophthalmologist. The primary goal of treatment is symptom relief. As blepharitis is typically chronic, patients must adhere to a consistent hygiene regimen to prevent recurrences. While there is no definitive cure, the prognosis is generally good, as blepharitis is more of a symptomatic condition than a serious health threat. Most patients respond well to treatment, although the condition is characterized by periods of exacerbation and remission.[69]

Blepharitis is typically managed by an interprofessional healthcare team, including a nurse practitioner, primary care provider, ophthalmologist, and internist. Each healthcare professional plays a distinct role in managing both the acute and long-term care of the condition. Effective collaboration among these specialists enhances patient satisfaction and adherence to treatment and also helps identify related systemic illnesses and comorbidities. This comprehensive approach leads to a more successful and individualized treatment plan.

Ophthalmologists and optometrists are often the primary healthcare providers responsible for diagnosing and treating blepharitis. They are crucial in conducting comprehensive eye examinations, including visualizing the meibomian glands and eyelid borders using diagnostic techniques such as slit-lamp biomicroscopy. These specialists are also responsible for educating patients about the chronic nature of blepharitis and recommending appropriate treatments, such as corticosteroids, antibiotics, or lid hygiene regimens. They monitor the progression of the condition and adjust treatment plans as needed, particularly for patients with complicated or unresponsive cases.

Effective communication between ophthalmologists and optometrists is crucial for patients who switch between these specialists for both routine and specialty eye care. Primary care physicians can manage underlying systemic conditions, such as diabetes, seborrheic dermatitis, and rosacea, which can worsen blepharitis. By addressing these comorbidities, primary care physicians help reduce blepharitis symptoms and prevent flare-ups. For instance, controlling seborrheic dermatitis can improve the prognosis of anterior blepharitis while effectively managing rosacea can alleviate the symptoms of posterior blepharitis. To expedite diagnosis and ensure prompt treatment, primary care physicians also play a key role in referring patients to eye specialists when they present with recurrent or persistent eyelid symptoms that may indicate blepharitis.

Ethics and patient-centered care are essential elements in the healthcare team’s approach to managing blepharitis. Healthcare providers can respect patient autonomy by educating patients about all available treatment options and involving them in decision-making. Given that blepharitis is a chronic condition, building trustworthy relationships with patients is critical for ensuring adherence to follow-up therapy and long-term management. As some modern therapies, such as thermal pulsation devices, can be costly, clinicians should also consider the financial impact of treatment. By discussing affordable alternatives, providers can help patients make well-informed decisions that align with their financial and personal circumstances.

A healthcare team–based approach to blepharitis management enhances treatment outcomes, increases patient satisfaction, and promotes adherence. Combining specialized eye care, systemic disease management, patient education, and pharmaceutical counseling provides a strong foundation for managing this complex condition. Nurses, pharmacists, and primary care physicians are crucial in patient education, medication management, and lifestyle counseling, facilitating a comprehensive approach. The interprofessional healthcare team should focus on delivering patient-centered care, minimizing recurrences, and addressing the complexities of this prevalent yet challenging ocular condition. Collaborating as a team, healthcare providers can deliver efficient, sustainable care that enhances both quality of life and long-term eye health.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Putnam CM. Diagnosis and management of blepharitis: an optometrist's perspective. Clinical optometry. 2016:8():71-78. doi: 10.2147/OPTO.S84795. Epub 2016 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 30214351]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHuggins AB, Carrasco JR, Eagle RC Jr. MEN 2B masquerading as chronic blepharitis and euryblepharon. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2019 Dec:38(6):514-518. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2019.1567800. Epub 2019 Jan 27 [PubMed PMID: 30688132]

Dietrich-Ntoukas T. [Chronic Blepharitis]. Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde. 2022 Nov:239(11):1381-1393. doi: 10.1055/a-1896-3441. Epub 2022 Aug 15 [PubMed PMID: 35970192]

Rodriguez-Garcia A, Loya-Garcia D, Hernandez-Quintela E, Navas A. Risk factors for ocular surface damage in Mexican patients with dry eye disease: a population-based study. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2019:13():53-62. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S190803. Epub 2018 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 30613133]

Choi FD, Juhasz MLW, Atanaskova Mesinkovska N. Topical ketoconazole: a systematic review of current dermatological applications and future developments. The Journal of dermatological treatment. 2019 Dec:30(8):760-771. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1573309. Epub 2019 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 30668185]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTavassoli S, Wong N, Chan E. Ocular manifestations of rosacea: A clinical review. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 2021 Mar:49(2):104-117. doi: 10.1111/ceo.13900. Epub 2021 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 33403718]

Lin A, Ahmad S, Amescua G, Cheung AY, Choi DS, Jhanji V, Mian SI, Rhee MK, Viriya ET, Mah FS, Varu DM, American Academy of Ophthalmology Preferred Practice Pattern Cornea/External Disease Panel. Blepharitis Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology. 2024 Apr:131(4):P50-P86. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2023.12.036. Epub 2024 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 38349296]

Ozkan J, Willcox MD. The Ocular Microbiome: Molecular Characterisation of a Unique and Low Microbial Environment. Current eye research. 2019 Jul:44(7):685-694. doi: 10.1080/02713683.2019.1570526. Epub 2019 Feb 4 [PubMed PMID: 30640553]

Khoo P, Ooi KG, Watson S. Effectiveness of pharmaceutical interventions for meibomian gland dysfunction: An evidence-based review of clinical trials. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 2019 Jul:47(5):658-668. doi: 10.1111/ceo.13460. Epub 2019 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 30561146]

Soh Qin R, Tong Hak Tien L. Healthcare delivery in meibomian gland dysfunction and blepharitis. The ocular surface. 2019 Apr:17(2):176-178. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2018.11.007. Epub 2018 Nov 17 [PubMed PMID: 30458245]

Fromstein SR, Harthan JS, Patel J, Opitz DL. Demodex blepharitis: clinical perspectives. Clinical optometry. 2018:10():57-63. doi: 10.2147/OPTO.S142708. Epub 2018 Jul 4 [PubMed PMID: 30214343]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRomanowski JE, Nayyar SV, Romanowski EG, Jhanji V, Shanks RMQ, Kowalski RP. Speciation and Antibiotic Susceptibilities of Coagulase Negative Staphylococci Isolated from Ocular Infections. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland). 2021 Jun 16:10(6):. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10060721. Epub 2021 Jun 16 [PubMed PMID: 34208455]

Wolf R, Orion E, Tüzün Y. Periorbital (eyelid) dermatides. Clinics in dermatology. 2014 Jan-Feb:32(1):131-40. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.05.035. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24314387]

Chioveanu FG, Niculet E, Torlac C, Busila C, Tatu AL. Beyond the Surface: Understanding Demodex and Its Link to Blepharitis and Facial Dermatoses. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2024:18():1801-1810. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S440199. Epub 2024 Jun 24 [PubMed PMID: 38948346]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSandford EC, Muntz A, Craig JP. Therapeutic potential of castor oil in managing blepharitis, meibomian gland dysfunction and dry eye. Clinical & experimental optometry. 2021 Apr:104(3):315-322. doi: 10.1111/cxo.13148. Epub 2021 Mar 10 [PubMed PMID: 33037703]

Rhee MK, Yeu E, Barnett M, Rapuano CJ, Dhaliwal DK, Nichols KK, Karpecki P, Mah FS, Chan A, Mun J, Gaddie IB. Demodex Blepharitis: A Comprehensive Review of the Disease, Current Management, and Emerging Therapies. Eye & contact lens. 2023 Aug 1:49(8):311-318. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0000000000001003. Epub 2023 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 37272680]

Lemp MA, Nichols KK. Blepharitis in the United States 2009: a survey-based perspective on prevalence and treatment. The ocular surface. 2009 Apr:7(2 Suppl):S1-S14 [PubMed PMID: 19383269]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchaumberg DA, Nichols JJ, Papas EB, Tong L, Uchino M, Nichols KK. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the subcommittee on the epidemiology of, and associated risk factors for, MGD. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2011 Mar:52(4):1994-2005. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6997e. Epub 2011 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 21450917]

Viso E, Rodríguez-Ares MT, Abelenda D, Oubiña B, Gude F. Prevalence of asymptomatic and symptomatic meibomian gland dysfunction in the general population of Spain. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2012 May 4:53(6):2601-6. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9228. Epub 2012 May 4 [PubMed PMID: 22427596]

Rim TH, Kang MJ, Choi M, Seo KY, Kim SS. Ten-year incidence and prevalence of clinically diagnosed blepharitis in South Korea: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 2017 Jul:45(5):448-454. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12929. Epub 2017 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 28183148]

Yeotikar NS, Zhu H, Markoulli M, Nichols KK, Naduvilath T, Papas EB. Functional and Morphologic Changes of Meibomian Glands in an Asymptomatic Adult Population. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2016 Aug 1:57(10):3996-4007. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-18467. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27490319]

Marcon C, Simeon V, Savignano C, Barillari G. Staphylococcus pasteuri isolated in extracorporeal photopheresis product in a patient affected by chalazion blepharitis. Transplant infectious disease : an official journal of the Transplantation Society. 2024 Aug:26(4):e14320. doi: 10.1111/tid.14320. Epub 2024 Jun 14 [PubMed PMID: 38874266]

Kudasiewicz-Kardaszewska A, Grant-Kels JM, Grzybowski A. Meibomian gland dysfunction and blepharitis: A common and still unsolved ophthalmic problem. Clinics in dermatology. 2023 Jul-Aug:41(4):491-502. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2023.08.005. Epub 2023 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 37574151]

Rocha KM, Farid M, Raju L, Beckman K, Ayres BD, Yeu E, Rao N, Chamberlain W, Zavodni Z, Lee B, Schallhorn J, Garg S, Mah FS, From the ASCRS Cornea Clinical Committee. Eyelid margin disease (blepharitis and meibomian gland dysfunction): clinical review of evidence-based and emerging treatments. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery. 2024 Aug 1:50(8):876-882. doi: 10.1097/j.jcrs.0000000000001414. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38350160]

Sharma N, Martin E, Pearce EI, Hagan S, Purslow C. Demodex Blepharitis: A Survey-Based Approach to Investigate Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Among Optometrists in India. Clinical optometry. 2023:15():55-64. doi: 10.2147/OPTO.S403837. Epub 2023 Apr 11 [PubMed PMID: 37069856]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLong CP, Ozzello DJ, Kikkawa DO, Liu CY. Cytomegalovirus Blepharitis and Keratitis Masquerading as Eyelid Malignancy. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2022 Jan-Feb 01:38(1):e34. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001992. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34085992]

Li H, Böhringer D, Maier P, Reinhard T, Lang SJ. Developing and validating a questionnaire to assess the symptoms of blepharitis accompanied by dry eye disease. Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 2023 Oct:261(10):2891-2900. doi: 10.1007/s00417-023-06104-2. Epub 2023 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 37243742]

Sabeti S, Kheirkhah A, Yin J, Dana R. Management of meibomian gland dysfunction: a review. Survey of ophthalmology. 2020 Mar-Apr:65(2):205-217. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2019.08.007. Epub 2019 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 31494111]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMergen B, Onal I, Gulmez A, Caytemel C, Yildirim Y. Conjunctival Microbiota and Blepharitis Symptom Scores in Patients With Ocular Rosacea. Eye & contact lens. 2023 Aug 1:49(8):339-343. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0000000000001008. Epub 2023 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 37363964]

Cartes C, Segovia C, Calonge M, Figueiredo FC. International survey on dry eye diagnosis by experts. Heliyon. 2023 Jun:9(6):e16995. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16995. Epub 2023 Jun 7 [PubMed PMID: 37484334]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNarang P, Donthineni PR, D'Souza S, Basu S. Evaporative dry eye disease due to meibomian gland dysfunction: Preferred practice pattern guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2023 Apr:71(4):1348-1356. doi: 10.4103/IJO.IJO_2841_22. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37026266]

Pyzia J, Mańkowska K, Czepita M, Kot K, Łanocha-Arendarczyk N, Czepita D, Kosik-Bogacka DI. Demodex Species and Culturable Microorganism Co-Infestations in Patients with Blepharitis. Life (Basel, Switzerland). 2023 Aug 29:13(9):. doi: 10.3390/life13091827. Epub 2023 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 37763231]

Fernández-Engroba J, Ferragut-Alegre Á, Oliva-Albaladejo G, de la Paz MF. In vitro evaluation of multiple antibacterial agents for the treatment of chronic staphylococcal anterior blepharitis. Archivos de la Sociedad Espanola de Oftalmologia. 2023 Jun:98(6):338-343. doi: 10.1016/j.oftale.2023.05.003. Epub 2023 May 18 [PubMed PMID: 37209719]

Rokohl AC, Wall K, Trester M, Wawer Matos PA, Guo Y, Adler W, Pine KR, Heindl LM. Novel point-of-care biomarkers of the dry anophthalmic socket syndrome: tear film osmolarity and matrix metalloproteinase 9 immunoassay. Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 2023 Mar:261(3):821-831. doi: 10.1007/s00417-022-05895-0. Epub 2022 Nov 11 [PubMed PMID: 36357674]

Gomez ML, Afshari NA, Gonzalez DD, Cheng L. Effect of Thermoelectric Warming Therapy for the Treatment of Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. American journal of ophthalmology. 2022 Oct:242():181-188. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2022.06.013. Epub 2022 Jun 25 [PubMed PMID: 35764104]

Shah PP, Stein RL, Perry HD. Update on the Management of Demodex Blepharitis. Cornea. 2022 Aug 1:41(8):934-939. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002911. Epub 2021 Nov 3 [PubMed PMID: 34743107]

Ramtohul P, Denis D. Paraneoplastic Dermatomyositis Presenting as Atopic Blepharitis. Ophthalmology. 2019 Oct:126(10):1423. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.05.031. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31543112]

Pflugfelder SC, Karpecki PM, Perez VL. Treatment of blepharitis: recent clinical trials. The ocular surface. 2014 Oct:12(4):273-84. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2014.05.005. Epub 2014 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 25284773]

Kanda Y, Kayama T, Okamoto S, Hashimoto M, Ishida C, Yanai T, Fukumoto M, Kunihiro E. Post-marketing surveillance of levofloxacin 0.5% ophthalmic solution for external ocular infections. Drugs in R&D. 2012 Dec 1:12(4):177-85. doi: 10.2165/11636020-000000000-00000. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23075336]

. . :(): [PubMed PMID: 1345157]

Veldman P, Colby K. Current evidence for topical azithromycin 1% ophthalmic solution in the treatment of blepharitis and blepharitis-associated ocular dryness. International ophthalmology clinics. 2011 Fall:51(4):43-52. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0b013e31822d6af1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21897139]

Karbassi E, Amiri-Ardekani E, Farsinezhad A, Shahesmaeili A, Abhari Y, Ziaesistani M, Pouryazdanpanah N, Derakhshani A, Jamshidi F, Tajadini H. The Efficacy of Kohl (Surma) and Erythromycin in Treatment of Blepharitis: An Open-Label Clinical Trial. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM. 2022:2022():6235857. doi: 10.1155/2022/6235857. Epub 2022 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 35111228]

Onghanseng N, Ng SM, Halim MS, Nguyen QD. Oral antibiotics for chronic blepharitis. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2021 Jun 9:6(6):CD013697. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013697.pub2. Epub 2021 Jun 9 [PubMed PMID: 34107053]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMurphy O, O'Dwyer V, Lloyd-McKernan A. The efficacy of tea tree face wash, 1, 2-Octanediol and microblepharoexfoliation in treating Demodex folliculorum blepharitis. Contact lens & anterior eye : the journal of the British Contact Lens Association. 2018 Feb:41(1):77-82. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2017.10.012. Epub 2017 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 29074306]

Murphy O, O' Dwyer V, Lloyd-McKernan A. The effect of lid hygiene on the tear film and ocular surface, and the prevalence of Demodex blepharitis in university students. Contact lens & anterior eye : the journal of the British Contact Lens Association. 2020 Apr:43(2):159-168. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2019.09.003. Epub 2019 Sep 20 [PubMed PMID: 31548151]

Lam PY, Shih KC, Fong PY, Chan TCY, Ng AL, Jhanji V, Tong L. A Review on Evidence-Based Treatments for Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. Eye & contact lens. 2020 Jan:46(1):3-16. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0000000000000680. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31834043]

Gomez ML, Jung J, Gonzales DD, Shacterman S, Afshari N, Cheng L. Comparison of manual versus automated thermal lid therapy with expression for meibomian gland dysfunction in patients with dry eye disease. Scientific reports. 2024 Sep 27:14(1):22287. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-72320-3. Epub 2024 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 39333153]

Siegel H, Merz A, Gross N, Bründer MC, Böhringer D, Reinhard T, Maier P. BlephEx-treatment for blepharitis: a prospective randomized placebo-controlled trial. BMC ophthalmology. 2024 Nov 18:24(1):503. doi: 10.1186/s12886-024-03765-3. Epub 2024 Nov 18 [PubMed PMID: 39558272]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSik Sarman Z, Cucen B, Yuksel N, Cengiz A, Caglar Y. Effectiveness of Intraductal Meibomian Gland Probing for Obstructive Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. Cornea. 2016 Jun:35(6):721-4. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000820. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27032021]

Warren NA, Maskin SL. Review of Literature on Intraductal Meibomian Gland Probing with Insights from the Inventor and Developer: Fundamental Concepts and Misconceptions. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2023:17():497-514. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S390085. Epub 2023 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 36789289]

Dall'Oglio F, Nasca MR, Gerbino C, Micali G. An Overview of the Diagnosis and Management of Seborrheic Dermatitis. Clinical, cosmetic and investigational dermatology. 2022:15():1537-1548. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S284671. Epub 2022 Aug 6 [PubMed PMID: 35967915]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSobolewska B, Schaller M, Zierhut M. Rosacea and Dry Eye Disease. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2022 Apr 3:30(3):570-579. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2021.2025251. Epub 2022 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 35226588]

Patel TS, Dalia Y. Seborrheic Dermatitis. JAMA dermatology. 2024 Dec 1:160(12):1371. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.1074. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39382873]

Santacroce L, Magrone T. Molluscum Contagiosum Virus: Biology and Immune Response. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2024:1451():151-170. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-57165-7_10. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38801577]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMeyer JJ. Rates of Herpes Simplex Virus Types 1 and 2 in Ocular and Peri-ocular Specimens. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2023 Jan:31(1):149-152. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2021.1998548. Epub 2021 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 34802388]

Shields JA, Saktanasate J, Lally SE, Carrasco JR, Shields CL. Sebaceous Carcinoma of the Ocular Region: The 2014 Professor Winifred Mao Lecture. Asia-Pacific journal of ophthalmology (Philadelphia, Pa.). 2015 Jul-Aug:4(4):221-7. doi: 10.1097/APO.0000000000000105. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26147013]

Philip AM, Stephenson A, Al-Dabbagh A, Ramezani K, Fernandez-Santos CC, Foster CS. Ocular Cicatricial Pemphigoid With IgM-Positive Biopsy. Cornea. 2023 Dec 1:42(12):1503-1505. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000003235. Epub 2023 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 36728301]

Schuler CF 4th, Billi AC, Maverakis E, Tsoi LC, Gudjonsson JE. Novel insights into atopic dermatitis. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2023 May:151(5):1145-1154. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2022.10.023. Epub 2022 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 36428114]

Sakimoto T, Sugiura T. Long-Term Prognosis of Anterior Blepharitis After Topical Antibiotics Treatment. Eye & contact lens. 2024 Oct 1:50(10):455-459. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0000000000001118. Epub 2024 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 39133177]

Sobolewska B, Doycheva D, Deuter CM, Schaller M, Zierhut M. Efficacy of Topical Ivermectin for the Treatment of Cutaneous and Ocular Rosacea. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2021 Aug 18:29(6):1137-1141. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2020.1727531. Epub 2020 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 32255398]

Moon J, Lee J, Kim MK, Hyon JY, Jeon HS, Oh JY. Clinical Characteristics and Therapeutic Outcomes of Pediatric Blepharokeratoconjunctivitis. Cornea. 2023 May 1:42(5):578-583. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000003120. Epub 2022 Aug 24 [PubMed PMID: 36036680]

Amer MM, Ho JW, Theotoka D, Wall S, Galor A, Cheng A, Miller D, Karp CL. Role of Topical 5-Fluorouracil in Demodex -Associated Blepharitis. Cornea. 2024 Jun 1:43(6):720-725. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000003470. Epub 2024 Jan 18 [PubMed PMID: 38236070]

Auw-Hädrich C, Reinhard T. [Blepharitis component of dry eye syndrome]. Der Ophthalmologe : Zeitschrift der Deutschen Ophthalmologischen Gesellschaft. 2018 Feb:115(2):93-99. doi: 10.1007/s00347-017-0606-8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29134275]

Tashbayev B, Chen X, Utheim TP. Chalazion Treatment: A Concise Review of Clinical Trials. Current eye research. 2024 Feb:49(2):109-118. doi: 10.1080/02713683.2023.2279014. Epub 2024 Jan 18 [PubMed PMID: 37937798]

Zdebik A, Zdebik N, Fischer M. Ocular manifestations of skin diseases with pathological keratinization abnormalities. Postepy dermatologii i alergologii. 2021 Feb:38(2):14-20. doi: 10.5114/ada.2021.104272. Epub 2021 Mar 10 [PubMed PMID: 34408561]

Zhu F, Tao JP. Bilateral upper and lower eyelid severe psoriasiform blepharitis: case report and review of literature. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2011 Sep-Oct:27(5):e138-9. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e318203d81f. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21464793]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJordal OM, Søndergaard CB, Hjortdal J. Blepharitis. Ugeskrift for laeger. 2023 Jul 17:185(29):. pii: V10220633. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37539802]

Di Zazzo A, Giannaccare G, Villani E, Barabino S. Uncommon Blepharitis. Journal of clinical medicine. 2024 Jan 25:13(3):. doi: 10.3390/jcm13030710. Epub 2024 Jan 25 [PubMed PMID: 38337403]

Hosseini K, Bourque LB, Hays RD. Development and evaluation of a measure of patient-reported symptoms of Blepharitis. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2018 Jan 11:16(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s12955-018-0839-5. Epub 2018 Jan 11 [PubMed PMID: 29325546]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence