Introduction

Palpable breast masses are a common condition encountered in an outpatient clinic. Approximately 3% of women are seen in the primary care setting due to a breast complaint.[1] Although the majority of these masses are associated with benign breast conditions, patients with palpable breast masses have an increased likelihood of having a breast malignancy.[2] Therefore, appropriate evaluation of any patient with a palpable breast mass is essential to optimizing outcomes. Although the majority of breast masses are present in adult women, children and men can also be affected. Indeed, male breast cancer is a well-documented condition and requires a considered index of suspicion for its timely diagnosis and intervention.[3][4]

A breast mass is associated with a broad spectrum of differential diagnoses, from benign breast abnormalities to advanced malignancies; therefore, a structured evaluation approach has been established to help clinicians balance appropriately assessing these lesions without submitting patients to unnecessary procedures. The assessment typically begins with a detailed history and clinical breast examination (CBE), followed by imaging for nearly all patients.[5] Depending on the patient's age, various imaging modalities are preferred for the initial diagnostic assessment of a palpable mass. Additional management approaches are recommended based on age and initial findings. Consequently, in-depth knowledge of the diagnostic pathway for a palpable breast mass is essential, as a systematic approach incorporating clinical, imaging, and biopsy evaluations ensures timely and accurate management.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

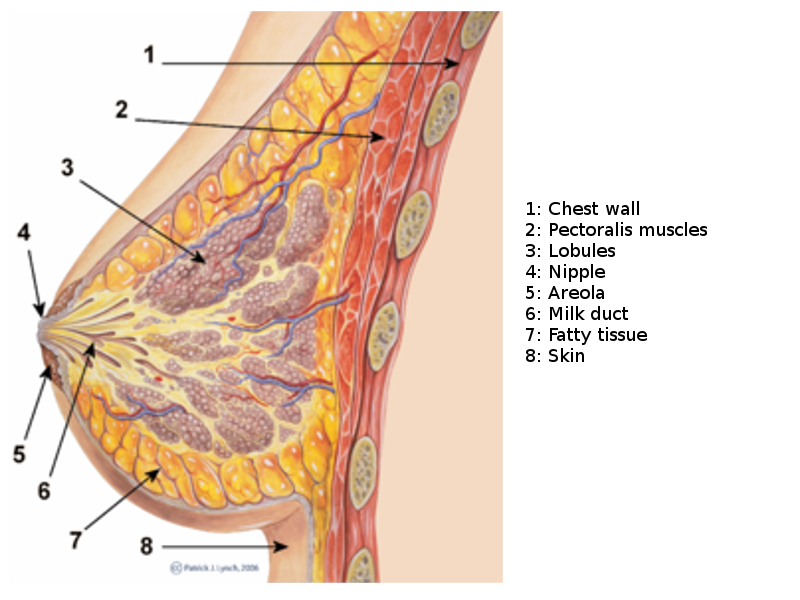

Breast Anatomy

The breast, or mammary gland, is a modified sweat gland containing various fibrous, glandular, and adipose tissue. Each breast has 15 to 20 lobes drained by lactiferous ducts that converge beneath the nipple in the subareolar region. The lobes are supported by fibrous stroma and fatty stroma. Lymphatic drainage is primarily through the axillary lymph nodes and involves the pectoral, subscapular, and internal mammary nodes.[6] (See Image. Breast Sagittal View). Breast tissue is present in children and males but is more developed in females of reproductive age due to hormonal surges that arise at puberty. Breast tissues involute significantly following menopause; the glandular tissue atrophies due to reduced circulating estrogen levels and is largely replaced by fatty tissue. Breast tissues and most breast pathologies are responsive to changes in hormone levels.[6]

Breast Mass Etiologies

The underlying etiology of a palpable breast mass includes a wide array of differential diagnoses. (Please refer to the Differential Diagnoses section for more information). Breast masses have various causes that differ based on age group and clinical presentation. In women younger than 25, the most common cause of a breast mass is a fibroadenoma; other causes in this population include giant juvenile fibroadenomas, cysts, hamartomas, fat necrosis, and inflammatory breast conditions (eg, abscesses). Breast carcinomas are a rare cause of a palpable breast lesion. For those 25 years and older, common causes of palpable breast masses include fibroadenomas and benign cysts, and the risk of a malignant condition increases as age increases.[7][8]

Benign and Malignant Breast Mass Risk Factors

Although the majority of these masses are associated with benign breast conditions, patients with palpable breast masses have an increased likelihood of having a breast malignancy.[2] Therefore, risk factors that increase a patient's chances for breast cancer should be considered when assessing the differential diagnoses of breast symptoms.

The primary risk factor for developing breast cancer is excess exposure to estrogens. Therefore, clinicians should inquire about lifetime estrogen exposure in all patients presenting a new breast mass. Early age of menarche, late age of first pregnancy, nulliparity, oral contraceptive or hormone replacement therapy, and late menopause increase estrogen exposure, while breastfeeding is a protective factor.[9] Male patients should be asked about previous hormonal treatments for prostate cancer, the use of finasteride or testosterone, episodes of orchitis/epididymitis, or previously diagnosed Klinefelter syndrome.[10] Other risk factors, eg, excess alcohol intake and obesity, are thought to increase endogenous estrogens.[11] Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Breast Cancer," for further information on breast cancer risk factors.

Risk factors for benign breast disorders are not well studied. However, a recent study found age, family history, and hormonal factors appear to influence the risk of benign breast lesions in a similar fashion as observed with breast malignancy. A family history of breast cancer significantly increases the risk for all types of benign breast conditions.[12]

Women of reproductive age with regular cycles, who were of older age at first childbirth, breastfed longer, or who currently use or have used oral contraceptives for ≥8 years appeared to have a high risk of fibroadenoma, while postmenopausal women have an increased risk of epithelial proliferation with atypia.[12] Additionally, hormone replacement therapy raises postmenopausal risks for epithelial proliferation with atypia, fibrocystic change, breast cysts, and fibroadenoma. Nulliparity increases the risk of breast cysts compared to multiples who have had 3 or more children but decreases the risk when compared to women who have only had 1 child. Obesity did not appear to increase the risk of benign breast disorders, according to this study, and in some instances, had a reduced risk.[12]

Epidemiology

According to recent studies, breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer in women.[13] A palpable breast mass is the most common presenting symptom of breast cancer. However, of the 3% of general practitioners' encounters with female patients that are due to breast complaints, benign breast disease is a more common cause of breast symptoms (eg, palpable masses and pain), with malignancy accounting for <10% of these cases.[14][1]

The incidence of benign breast conditions varies based on age and type of lesion. Fibroadenomas account for 95% of palpable breast masses in adolescent girls and 12% of menopausal women.[8][7] A recent study found fibroadenomas, epithelial proliferation, and fibrocystic changes are most common in women aged 25, with incidence rates of 45, 32, and 42 per 100,000 person-years, which increases to 81, 55, and 140 per 100,000, respectively, at age 40, and declines after age 55.[12]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of palpable breast masses varies depending on the underlying etiology. Please see StatPearls' companion resources, "Breast Cancer," "Breast Cyst," "Breast Fibroadenoma," "Fibrocystic Breast Disease," and "Breast Fat Necrosis," for further information on the pathophysiology of these breast disorders.

History and Physical

The clinical assessment of palpable breast masses primarily involves a thorough and accurate history of the lesion's associated symptomatic features, breast cancer risk factors, and CBE.[15][8] The CBE is the initial component of the standard triple assessment performed to evaluate breast lesions for potential malignancy.[16]

Clinical History

Patients presenting with complaints of a new breast mass should have a thorough history performed to characterize the lesion accurately. Clinicians should inquire about the mass's onset, duration, changes in size, pain, nipple discharge, and skin changes (eg, ulceration, eczema, or tethering).[7][8] These characteristics can help suggest potential diagnoses initially. For instance, an acutely tender breast lump is more likely to be an abscess or hematoma secondary to trauma. Cancerous breast masses rarely present with pain, although the presence of pain should not exclude neoplastic lesions from the differential. A history of recent pregnancy or breastfeeding may indicate that a condition associated with lactation is more likely (eg, mastitis or galactocele).[17] Nipple changes or discharge merits attention, as these can correlate with some less common breast tumors.[18][9] A history of any associated systemic symptoms should also be obtained, including weight loss, dyspnea, and bone pain, which may suggest potential malignancy.[19]

Establishing the duration for which the mass has been present is not always possible. Patients who do not regularly perform breast self-examination may not notice a breast lump until it has reached a significant size. Indeed, a proportion of breast lumps are identified through routine screening, so this is not necessarily an accurate way of determining the acuity of such a mass.[7] Furthermore, clinicians should establish whether the mass has developed in association with trauma or other symptoms, as well as if the mass appears to be rapidly growing or changing.

Breast cancer risk factors

Family history is a key risk factor for breast cancer. Establishing an accurate family history is crucial, including relatives diagnosed with non-breast cancers, especially at a young age. Risk calculators (eg, Tyrer–Cuzick model) can be instrumental in generating an accurate risk profile.[20][7] Additionally, a detailed understanding of the patient's medical history and medications is a crucial component of calculating a patient's breast cancer risk. The primary risk factor for developing breast cancer is excess exposure to estrogens. Therefore, clinicians should inquire about lifetime estrogen exposure in all patients presenting a new breast mass, including oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, and reproductive history. A history of smoking and alcohol consumption should also be obtained.[7][12]

Clinical Breast Examination

Clinical examination of a breast lump is the first stage in the triple-assessment approach. Both breasts and axillae should be examined meticulously by the clinician, and a physical examination of other body systems should be carried out as indicated by the history. Although it can be tempting to give more importance to more targeted imaging modalities, eg, mammography or ultrasound, the findings of the physical examination are crucial for the effective diagnosis and management of breast disease.[21] Repeated studies have indicated that optimal sensitivity and specificity can be achieved only by combining all 3 assessments.[16][21]

Clinical breast examination is often conducted with a chaperone to make the patient feel more comfortable. The entire chest and abdomen should be exposed, and the exam should be conducted with the patient in the supine or both supine and seated positions.[8][7] Each breast and axilla should undergo a visual inspection, looking for skin changes, nipple discharge, visible masses or asymmetry, and tethering to underlying structure; this feature can be exaggerated by asking the patient to place their hands on their hips and lift the arms.[22][8] The breasts can most easily be palpated by asking the patient to lie back at approximately 30 degrees and rest their palm up underneath their head.

Palpation of each breast must proceed in a structured manner; generally, clinicians use a 4-quadrant approach (upper outer, upper inner, lower outer, and lower inner quadrants), followed by palpating the areola and the axillary tail. Particular attention should be paid to the inframammary fold and the axillary tail. The unaffected breast is examined first, and the tissue is assessed for consistency. Masses are most often detected in the upper outer quadrant, as most breast tissue is located here. The nipple-areola complex should also be examined.[7]

Palpable breast masses should be described in location, size, shape, tenderness, fluctuance, mobility, texture, and pulsatility. If the patient describes nipple discharge that is not immediately visualized, it is appropriate to ask the patient to express the discharge themselves before the clinician attempts to do so.[23][8] Following palpation of the breast, the clinician must always palpate the axilla and supraclavicular region for lymphadenopathy. This area may present with enlarged, tender, or firm nodes, the number and nature of which should be documented. During the examination of the axilla, the clinician should take the weight of the patient's arm to relax the pectoralis muscles.[24]

Evaluation

Breast Imaging Classification

Breast imaging findings are classified by their Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) category, which correlates imaging findings with their probability of underlying malignancy and recommends a broad treatment strategy. This standard allows breast imaging to be described according to a certain structure, including the density of breast tissue, presence and location of a mass or masses, calcifications, asymmetry, and any associated features. The BI-RADS categories range from 0 to 6.[25]

The BIRADS system includes different mass classifications depending on the imaging modality. In mammography, to be considered a mass, the lesion must be visible in 2 different projections, have convex outer borders, and be denser in the center than on the periphery.[26][25] In ultrasound, a mass requires visualization in 2 different planes. Masses are defined according to their shape, margin, and density. In terms of shape, a mass can be categorized as round, oval, or irregular. Circumscribed margins are more apt to be benign, whereas microlobulated, indistinct, or spiculated margins are more likely malignant. The margin may also appear obscured. Mass density is compared to surrounding normal tissues - higher, equal, or lower - or may reflect fat within the mass.[27][25]

Table. Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System

| Category | Findings | Recommendation | Cancer Probability |

| 0 | Inadequate or incomplete study | Repeat imaging | N/A |

| 1 | Negative (ie, normal study) | Continue routine screening | Close to 0% |

| 2 | Benign | Continue routine screening | Close to 0% |

| 3 | Probably benign | Follow up in 6 to 12 months | <2% |

| 4 | Suspicious (subdivided into 4a, 4b and 4c) | Biopsy | 2% to 95 % |

| 5 | Highly suggestive of malignancy | Biopsy | >95% |

| 6 | Biopsy proven | 100% |

Radiological Assessment

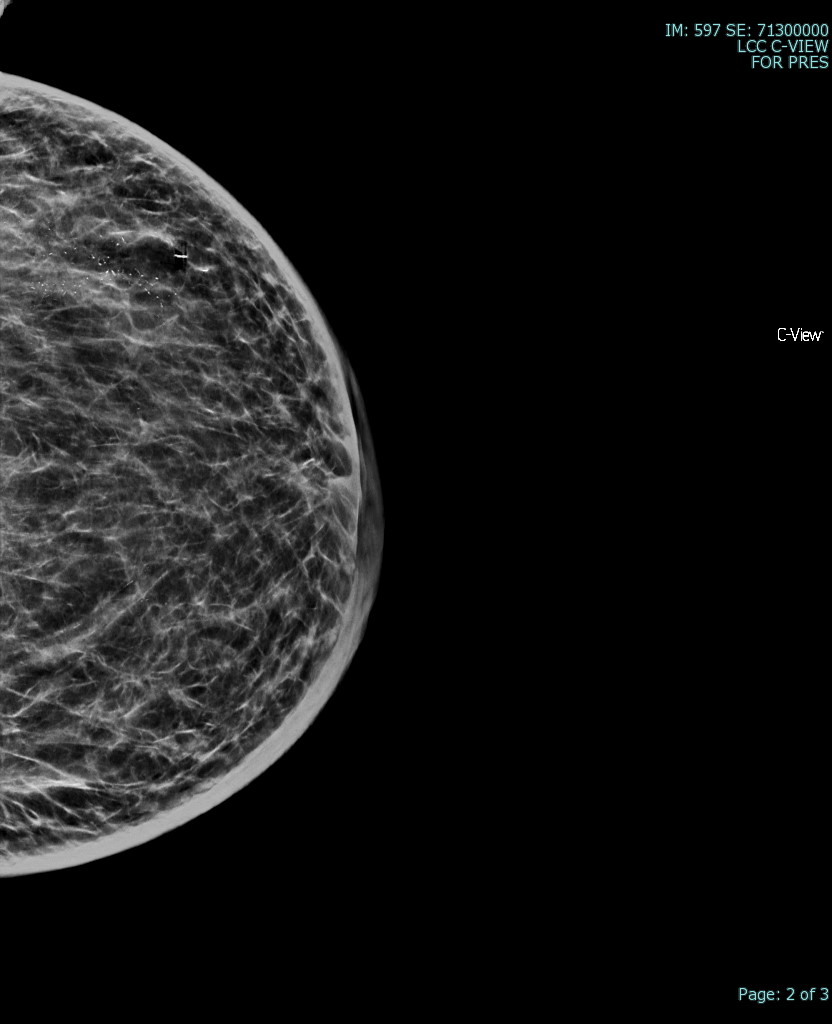

The most common radiological modalities for imaging breast tissue are mammography, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (see Image. Superficial Vein With an Area of Intraluminal Thrombus, Ultrasound). Age-specific recommendations have been established to optimize the effectiveness of these diagnostic studies. The following imaging guidelines have been proposed by the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria for the evaluation of new palpable breast masses based on the patient's age:

- For women 40 years and older: Either diagnostic mammography or digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) is recommended as the initial imaging modality. Mammography alone has been found to identify abnormalities with a sensitivity of 86% to 91% (see Image. Breast Mammogram).[28] If initial imaging has BI-RADS 1 to 3 findings, ultrasound is recommended to characterize a palpable mass further. Ultrasound is also recommended if mammogram imaging is unable to visualize a palpable mass, as 40% of benign palpable masses are only seen on ultrasound.[8][28]

- Women younger than 30: For palpable masses in these women with low clinical suspicion, follow-up over 1 to 2 menstrual cycles is appropriate. Ultrasound imaging should be performed if the mass remains after the observation period. However, ultrasound imaging should be performed initially in those with abnormal findings on CBE (eg, enlarged, fixed, hard, and heterogeneous texture).[1] Ultrasound is preferred for women younger than 30 due to denser breast tissue and lower cancer incidence in this group.[8][28] If ultrasound results show BI-RADS 1, a diagnostic mammogram is appropriate for high clinical suspicion.[28]

- Women aged between 30 and 39: Ultrasound, DBT, and mammography may be considered for initial imaging of a palpable mass. However, diagnostic mammography is preferred in high-risk patients or those with suspicious findings on CBE, as mammogram facilitates clinical assessment of the disease extent in women older than 30. Concordance between imaging findings and clinical examination is essential for accurate diagnosis.[8][28]

Ultrasound imaging is preferred to mammography in younger women and men as their breast tissue tends to be denser, with a much lower proportion of fatty tissue. This dense tissue impedes the accuracy of mammography and makes it more challenging to detect microcalcifications.[29] Magnetic resonance imaging is not typically recommended due to high costs, false-positive rates, and lower specificity. It may be reserved for specific cases, such as distinguishing scar tissue from recurrence in post-lumpectomy patients or screening high-risk individuals (eg, those with known underlying BRCA mutations).[5]

Pathology Analysis

The third aspect of triple assessment requires an invasive procedure to allow pathological diagnosis. Pathology analysis involves either fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) or core biopsy.[16] Cytology allows an analysis of cells in isolation, while histological examination of a biopsy can provide more detail about the architecture of tissues. These invasive procedures involve risks to the patient and should, therefore, only occur when the index of suspicion is present. Whether to perform FNAB or core biopsy depends on several factors, including the expertise of the clinician, available diagnostic equipment, and the site of the lesion. However, core biopsy is generally preferred over FNAB due to its decreased incidence of insufficient tissue collection and higher sensitivity and specificity than FNAB.[30][8] Breast cancers diagnosed with an FNAB require core needle biopsy confirmation with immunohistochemical evaluation before treatment is initiated.[7] Please see StatPearls' companion resources, "Fine Needle Aspiration of Breast Masses" and "Stereotactic and Needle Breast Biopsy," for more information on these procedures.

Excisional biopsy was once the standard method for diagnosing palpable breast masses and suspicious nonpalpable lesions; however, core needle biopsy is now preferred as it is less damaging to surrounding breast tissue while providing accurate histologic diagnosis. An excisional breast biopsy is now primarily reserved for specific situations, including:

- Imaging and core biopsy results that are discordant

- Nondiagnostic core biopsy specimens

- Lesions inaccessible to core biopsy due to location or patient anatomy

- Findings of atypical hyperplasia or lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) [8]

Treatment / Management

The following initial management recommendations for new palpable breast masses are based on BI-RADS recommendations and the patient's age:

- Women 30 years and older: No further evaluation is indicated for a diagnostic mammogram demonstrating a lesion with definitively benign findings. An ultrasound is recommended for diagnostic mammogram findings of BI-RADS 1 to 3 to characterize the breast mass further. However, if mammogram and ultrasound are unable to visualize a palpable mass (ie, BI-RADS 1) but clinical suspicion is low, follow-up for 1 to 2 years is preferred; palpable masses with high clinical suspicion should be evaluated with tissue biopsy. Clinicians should proceed to tissue biopsy if initial mammogram imaging has BI-RADS 4 to 5 findings.[8][28]

- Women younger than 30: If no lesion is identified on initial ultrasound imaging for a palpable mass with low clinical suspicion, follow-up over 1 to 2 years with repeated imaging and CBE is appropriate. However, a tissue biopsy is recommended if a size increase or other suspicious findings are noted during follow-up. A diagnostic mammogram is recommended for those with suspicious findings on CBE (eg, enlarged, fixed, hard, and heterogeneous texture) and BI-RADS 1 findings on ultrasound.[8][28]

The management recommendations for breast masses categorized as BI-RADS 2 to 5 are similar in women of all ages. BI-RADS 2 findings may be routinely followed if asymptomatic. BI-RADS 3 findings with low clinical suspicion may be monitored by CBE and diagnostic mammogram or ultrasound every 6 to 12 months for 1 to 2 years; however, tissue biopsy is recommended if clinical suspicion is high. A tissue biopsy should be performed if initial or second-line ultrasound imaging has BI-RADS 4 or 5 findings. Ultimately, the treatment of a breast lump varies depending on the condition diagnosed following appropriate follow-up and histologic assessment and may involve an interprofessional approach, with input from the oncology, radiology, pathology, surgical, specialist nursing, anesthetic teams, palliative care, social workers, and psychology teams where indicated.[8][28]

Please see StatPearls' companion resources, "Breast Cancer," "Breast Cyst," "Breast Fibroadenoma," "Fibrocystic Breast Disease," "Phyllodes Tumor of the Breast," "Male Breast Cancer," "Inflammatory Breast Cancer," "Breast Abscess," and "Breast Fat Necrosis," for further information on the specific management of these breast disorders.

Differential Diagnosis

Breast masses have various causes that differ based on age group and clinical presentation. In women younger than 25, the most common causes for a breast mass are benign conditions, including fibroadenoma, giant juvenile fibroadenomas, cysts, hamartomas, fat necrosis, and inflammatory breast conditions (eg, abscesses). For those 25 years and older, palpable breast masses are also commonly caused by benign breast abnormalities; however, the risk of a malignant underlying condition increases as age increases.[7][8] Please see StatPearls' companion resources, "Breast Cancer," "Breast Cyst," "Breast Fibroadenoma," "Fibrocystic Breast Disease," "Breast Abscess," and "Breast Fat Necrosis," for further information on these breast disorders. Differential diagnoses that should be considered when evaluating patients with a palpable breast mass include:

- Breast cyst

- Breast abscess

- Breast carcinoma

- Fibrocystic changes

- Fibroadenomas

- Lactating adenoma

- Phlegmon

- Prominent lactiferous sinus

- Traumatic fat necrosis

- Hematoma

- Hamartoma [1][8][17]

Males presenting with breast masses must be treated with a high degree of suspicion to rule out malignant tumors.[4] Imaging male breasts should utilize ultrasound as male breast tissue is not amenable to mammography. In males, central masses located behind the nipple may be attributable to gynecomastia. Gynecomastia is abnormal breast tissue development in males, which can correlate with several causes, including chromosomal disorders, liver failure, paraneoplastic syndromes, and drugs such as spironolactone and calcium channel blockers.[31] Due to hormonal variations, physiological gynecomastia may also be present in the neonatal period, at puberty, and in older males.[32]

Prognosis

The prognosis of a palpable breast mass primarily depends on whether the underlying etiology is benign or malignant. The majority of breast masses prove to be benign and have an excellent prognosis. However, the prognosis of breast carcinoma varies based on the stage at diagnosis. Stage 0 and stage I both have a 100% 5-year survival rate. The 5-year survival rate of stage II and stage III breast cancer is about 93% and 72%, respectively. Only 22% of stage IV breast cancer patients will survive their next 5 years.[33]

Complications

The primary risks involved in breast mass evaluation are during the biopsy procedures. Risk factors associated with both FNA and CNB include bleeding at the biopsy site, anesthesia risks, bruising, mild pain, infection, patient anxiety and discomfort, hematoma, and altered breast sensation; however, a core needle biopsy generally carries a slightly higher risk of complications due to the larger tissue sample obtained.[34]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Deterrence and patient education are critical components in managing palpable breast masses. Proactive patient education empowers individuals with knowledge about breast health, normal breast anatomy, and the importance of early evaluation of any unusual findings. Patients should be encouraged to perform regular self-breast exams and promptly report changes such as new lumps, nipple discharge, skin changes, or rapid growth of existing masses. Awareness of risk factors, including family history of breast cancer and lifestyle influences, is essential in fostering vigilance and early detection. Clinicians should also address misconceptions and alleviate fears that may prevent patients from seeking timely care.

Deterrence efforts focus on promoting preventive strategies and ensuring access to care through a patient-centered and interprofessional approach. Clinicians must emphasize the importance of routine screenings and, when indicated, follow-up evaluations. For patients with a higher risk of malignancy, including those with atypical findings on imaging or biopsy, education about surveillance options, genetic counseling, and lifestyle modifications is crucial. Involving interprofessional teams ensures patients receive consistent and comprehensive information while enhancing adherence to care plans. By fostering trust, improving health literacy, and maintaining open communication, healthcare teams can improve early detection rates, optimize outcomes, and reduce the burden of breast disease.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of breast masses requires a comprehensive interprofessional approach, given the diverse range of potential causes and the complexity of diagnosis and treatment. Effective collaboration between primary care clinicians, specialists, and subspecialists is essential to ensure accurate evaluation and appropriate management. Clear communication and well-defined roles are critical for coordinating care and avoiding delays or missteps. Clinics that employ a triple assessment model exemplify interprofessional teamwork, bringing together physicians, specialist nurses, clinical pathologists, radiographers, sonographers, and radiologists. By fostering consensus through shared expertise, these teams provide accurate and timely diagnoses while ensuring a patient-centered approach to care.

Interprofessional collaboration extends beyond diagnosis to treatment and follow-up. Depending on the underlying cause of the breast mass, care may involve surgeons, oncologists, immunologists, genetic counselors, and specialized nurses who guide patients through their care journey. Each team member contributes unique expertise, whether performing diagnostic imaging, conducting biopsies, or providing patient education and support. By maintaining open lines of communication and leveraging collective knowledge, healthcare teams can address not only the medical aspects of breast mass management but also the emotional and psychological needs of patients. This coordinated approach improves patient outcomes, enhances safety, and ensures that care remains comprehensive and centered on the patient.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Breast Sagittal View. This illustration shows the chest wall, pectoralis, lobules, nipple, areola, milk duct, fatty tissue, and skin.

PJ Lynch and Morgoth666, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Salzman B, Collins E, Hersh L. Common Breast Problems. American family physician. 2019 Apr 15:99(8):505-514 [PubMed PMID: 30990294]

Brown AL, Phillips J, Slanetz PJ, Fein-Zachary V, Venkataraman S, Dialani V, Mehta TS. Clinical Value of Mammography in the Evaluation of Palpable Breast Lumps in Women 30 Years Old and Older. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2017 Oct:209(4):935-942. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.17088. Epub 2017 Aug 4 [PubMed PMID: 28777649]

Kamal MZ, Banu NR, Alam MM, Das UK, Karmoker RK. Evaluation of Breast Lump - Comparison between True-cut Needle Biopsy and FNAC in MMCH: A Study of 100 Cases. Mymensingh medical journal : MMJ. 2020 Jan:29(1):48-54 [PubMed PMID: 31915335]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYuan WH, Li AF, Chou YH, Hsu HC, Chen YY. Clinical and ultrasonographic features of male breast tumors: A retrospective analysis. PloS one. 2018:13(3):e0194651. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194651. Epub 2018 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 29558507]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceExpert Panel on Breast Imaging:, Moy L, Heller SL, Bailey L, D'Orsi C, DiFlorio RM, Green ED, Holbrook AI, Lee SJ, Lourenco AP, Mainiero MB, Sepulveda KA, Slanetz PJ, Trikha S, Yepes MM, Newell MS. ACR Appropriateness Criteria(®) Palpable Breast Masses. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR. 2017 May:14(5S):S203-S224. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.02.033. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28473077]

Khan YS, Fakoya AO, Sajjad H. Anatomy, Thorax, Mammary Gland. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31613446]

Malherbe F, Nel D, Molabe H, Cairncross L, Roodt L. Palpable breast lumps: An age-based approach to evaluation and diagnosis. South African family practice : official journal of the South African Academy of Family Practice/Primary Care. 2022 Sep 23:64(1):e1-e5. doi: 10.4102/safp.v64i1.5571. Epub 2022 Sep 23 [PubMed PMID: 36226953]

. Practice Bulletin No. 164: Diagnosis and Management of Benign Breast Disorders. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2016 Jun:127(6):e141-e156. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001482. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27214189]

Akram M, Iqbal M, Daniyal M, Khan AU. Awareness and current knowledge of breast cancer. Biological research. 2017 Oct 2:50(1):33. doi: 10.1186/s40659-017-0140-9. Epub 2017 Oct 2 [PubMed PMID: 28969709]

Yalaza M, İnan A, Bozer M. Male Breast Cancer. The journal of breast health. 2016 Jan:12(1):1-8. doi: 10.5152/tjbh.2015.2711. Epub 2016 Jan 1 [PubMed PMID: 28331724]

Travis RC, Key TJ. Oestrogen exposure and breast cancer risk. Breast cancer research : BCR. 2003:5(5):239-47 [PubMed PMID: 12927032]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJohansson A, Christakou AE, Iftimi A, Eriksson M, Tapia J, Skoog L, Benz CC, Rodriguez-Wallberg KA, Hall P, Czene K, Lindström LS. Characterization of Benign Breast Diseases and Association With Age, Hormonal Factors, and Family History of Breast Cancer Among Women in Sweden. JAMA network open. 2021 Jun 1:4(6):e2114716. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.14716. Epub 2021 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 34170304]

Ahmad A. Breast Cancer Statistics: Recent Trends. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2019:1152():1-7. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-20301-6_1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31456176]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStachs A, Stubert J, Reimer T, Hartmann S. Benign Breast Disease in Women. Deutsches Arzteblatt international. 2019 Aug 9:116(33-34):565-574. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0565. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31554551]

Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, Perry MC. Breast Lump. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 1990:(): [PubMed PMID: 21250122]

Karim MO, Khan KA, Khan AJ, Javed A, Fazid S, Aslam MI. Triple Assessment of Breast Lump: Should We Perform Core Biopsy for Every Patient? Cureus. 2020 Mar 30:12(3):e7479. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7479. Epub 2020 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 32351857]

Mitchell KB, Johnson HM, Eglash A, Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. ABM Clinical Protocol #30: Breast Masses, Breast Complaints, and Diagnostic Breast Imaging in the Lactating Woman. Breastfeeding medicine : the official journal of the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. 2019 May:14(4):208-214. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2019.29124.kjm. Epub 2019 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 30892931]

Duijm LE, Guit GL, Hendriks JH, Zaat JO, Mali WP. Value of breast imaging in women with painful breasts: observational follow up study. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 1998 Nov 28:317(7171):1492-5 [PubMed PMID: 9831579]

Tahara RK, Brewer TM, Theriault RL, Ueno NT. Bone Metastasis of Breast Cancer. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2019:1152():105-129. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-20301-6_7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31456182]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrewer HR, Jones ME, Schoemaker MJ, Ashworth A, Swerdlow AJ. Family history and risk of breast cancer: an analysis accounting for family structure. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2017 Aug:165(1):193-200. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4325-2. Epub 2017 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 28578505]

Provencher L, Hogue JC, Desbiens C, Poirier B, Poirier E, Boudreau D, Joyal M, Diorio C, Duchesne N, Chiquette J. Is clinical breast examination important for breast cancer detection? Current oncology (Toronto, Ont.). 2016 Aug:23(4):e332-9. doi: 10.3747/co.23.2881. Epub 2016 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 27536182]

Henderson JA, Duffee D, Ferguson T. Breast Examination Techniques. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083747]

Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, Barry M. Nipple Discharge. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 1990:(): [PubMed PMID: 21250127]

Sultania M, Kataria K, Srivastava A, Misra MC, Parshad R, Dhar A, Hari S, Thulkar S. Validation of Different Techniques in Physical Examination of Breast. The Indian journal of surgery. 2017 Jun:79(3):219-225. doi: 10.1007/s12262-016-1470-5. Epub 2016 Apr 4 [PubMed PMID: 28659675]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceEghtedari M, Chong A, Rakow-Penner R, Ojeda-Fournier H. Current Status and Future of BI-RADS in Multimodality Imaging, From the AJR Special Series on Radiology Reporting and Data Systems. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2021 Apr:216(4):860-873. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.24894. Epub 2021 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 33295802]

Barazi H, Gunduru M. Mammography BI RADS Grading. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969638]

Magny SJ, Shikhman R, Keppke AL. Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083600]

Expert Panel on Breast Imaging, Klein KA, Kocher M, Lourenco AP, Niell BL, Bennett DL, Chetlen A, Freer P, Ivansco LK, Jochelson MS, Kremer ME, Malak SF, McCrary M, Mehta TS, Neal CH, Porpiglia A, Ulaner GA, Moy L. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Palpable Breast Masses: 2022 Update. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR. 2023 May:20(5S):S146-S163. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2023.02.013. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37236740]

Tan KP, Mohamad Azlan Z, Rumaisa MP, Siti Aisyah Murni MR, Radhika S, Nurismah MI, Norlia A, Zulfiqar MA. The comparative accuracy of ultrasound and mammography in the detection of breast cancer. The Medical journal of Malaysia. 2014 Apr:69(2):79-85 [PubMed PMID: 25241817]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTripathi K, Yadav R, Maurya SK. A Comparative Study Between Fine-Needle Aspiration Cytology and Core Needle Biopsy in Diagnosing Clinically Palpable Breast Lumps. Cureus. 2022 Aug:14(8):e27709. doi: 10.7759/cureus.27709. Epub 2022 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 36081980]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceVandeven HA, Pensler JM. Gynecomastia. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613563]

Johnson RE, Murad MH. Gynecomastia: pathophysiology, evaluation, and management. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2009 Nov:84(11):1010-5. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60671-X. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19880691]

Gradishar WJ, Moran MS, Abraham J, Aft R, Agnese D, Allison KH, Anderson B, Burstein HJ, Chew H, Dang C, Elias AD, Giordano SH, Goetz MP, Goldstein LJ, Hurvitz SA, Isakoff SJ, Jankowitz RC, Javid SH, Krishnamurthy J, Leitch M, Lyons J, Mortimer J, Patel SA, Pierce LJ, Rosenberger LH, Rugo HS, Sitapati A, Smith KL, Smith ML, Soliman H, Stringer-Reasor EM, Telli ML, Ward JH, Wisinski KB, Young JS, Burns J, Kumar R. Breast Cancer, Version 3.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2022 Jun:20(6):691-722. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2022.0030. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35714673]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceŁukasiewicz E, Ziemiecka A, Jakubowski W, Vojinovic J, Bogucevska M, Dobruch-Sobczak K. Fine-needle versus core-needle biopsy - which one to choose in preoperative assessment of focal lesions in the breasts? Literature review. Journal of ultrasonography. 2017 Dec:17(71):267-274. doi: 10.15557/JoU.2017.0039. Epub 2017 Dec 29 [PubMed PMID: 29375902]