Introduction

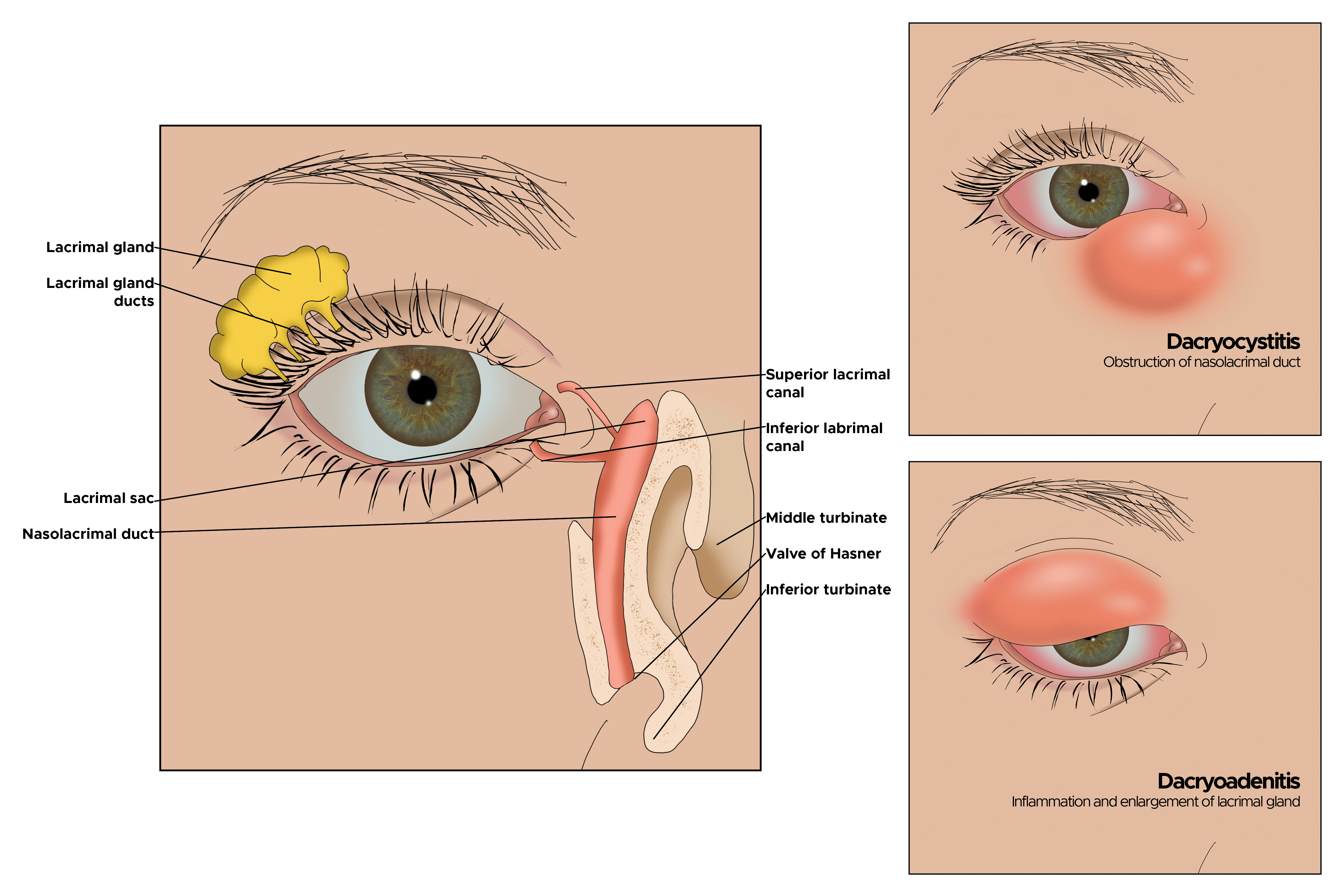

Dacryoadenitis refers to inflammation of the lacrimal gland, a key component of the ocular adnexa responsible for tear secretion (see Image. Dacryoadenitis).[1] The condition may present in acute or chronic forms, affect one or both eyes, and arise from infectious, autoimmune, or idiopathic causes.[2]

The lacrimal gland is a bilateral, lobulated, almond-shaped structure located in the superotemporal orbit. This structure consists of palpebral and orbital lobes and produces the aqueous component of the tear film, which is vital for ocular surface protection and homeostasis. Encased in dense connective tissue, the lacrimal gland contains a mix of acinar and ductal cells, along with immune cells such as immunoglobulin A-secreting plasma cells and T lymphocytes.[3]

The course of dacryoadenitis depends on its cause. Acute cases are typically infectious and self-limiting, while chronic forms may indicate an underlying systemic condition such as sarcoidosis or immunoglobulin G4-related (IgG4-related) disease (IgG4-RD).[4] Dacryoadenitis may spread through direct extension from adjacent tissues, hematogenous dissemination, or lymphatic propagation.[5]

Dacryoadenitis presents clinically with eyelid edema, discomfort, and erythema localized to the superotemporal orbit.[6] In more severe cases, ocular motility disturbances, conjunctival chemosis, and proptosis may develop.[7] Chronic dacryoadenitis often leads to persistent glandular hypertrophy and progressive fibrosis, which can result in irreversible dysfunction.[8]

Distinguishing between acute and chronic dacryoadenitis is essential for accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment.[9] Viral dacryoadenitis resolves spontaneously, while bacterial cases may require antibiotic therapy.[10] Inflammatory disease may respond to steroids or follow a chronic relapsing course, necessitating long-term management to maintain remission.[11]

Ongoing research continues to provide insights into immune-mediated mechanisms and histopathological subtypes of dacryoadenitis. The recognition of IgG4-related dacryoadenitis as a distinct entity has refined the diagnostic criteria, enabling more precise classification and targeted treatment.[12] Future studies aim to elucidate underlying mechanisms further and optimize therapeutic approaches for this complex condition.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Lacrimal gland inflammation may be acute or chronic, infectious or noninfectious. Acute dacryoadenitis is frequently infectious and unilateral.[13] Infection most often ascends from the conjunctiva but may also originate from the skin, penetrating trauma, or hematogenous seeding in bacteremia.

Viral pathogens are more common than bacterial causes, particularly in children and young adults. Viruses typically lead to acute nonsuppurative dacryoadenitis. Epstein-Barr virus is the most common viral etiology.[14] Other frequent viral pathogens include the following:

Bacterial infections tend to cause suppuration. Staphylococcus aureus is the primary bacterial pathogen, with Streptococcus pneumoniae and gram-negative rods also implicated.[20][21] Fungal causes, though rare, include Histoplasma, Blastomyces, and Nocardia.[22] Aspergillus and Candida infections are uncommon but severe, primarily affecting individuals with compromised immune function.[23] These infections may present insidiously with chronic inflammation and may require antifungal therapy alongside surgical intervention if tissue necrosis develops.[24] Chronic infectious dacryoadenitis is uncommon, with some cases linked to Mycobacterium tuberculosis.[25][26] Parasitic infections, though rare, have been associated with dacryoadenitis, particularly in endemic regions where protozoal or helminthic infestations are prevalent.[27]

Chronic dacryoadenitis is more often inflammatory. Noninfectious dacryoadenitis is frequently associated with autoimmune disorders, including Sjögren syndrome, sarcoidosis, Crohn disease, and granulomatosis with polyangiitis.[28]

Despite advancements in understanding and diagnostic testing, many inflammatory cases remain idiopathic.[29] Idiopathic dacryoadenitis is a diagnosis of exclusion established when no specific infectious or autoimmune cause is identified.[30] Histopathological evaluation may aid in assessing suspected idiopathic cases. The growing interest in IgG4-related dacryoadenitis has led to its recognition as a distinct entity, accounting for 23% to 35% of cases previously classified as idiopathic orbital inflammation.[31][32]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of dacryoadenitis is not well documented, but it occurs less frequently than dacryocystitis, which involves inflammation or infection of the lacrimal sac. Historical literature estimates its incidence at approximately 1 in 10,000 ophthalmic cases. Acute dacryoadenitis most commonly affects children and young adults, with viral infections being the predominant cause.[33] Bacterial suppurative dacryoadenitis is less frequent and may result from Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus, or Haemophilus infections.[34]

In contrast, chronic dacryoadenitis is more common in middle-aged and older individuals with underlying systemic inflammatory conditions. When associated with autoimmune disease, dacryoadenitis appears to be more prevalent in women, reflecting the broader gender predilection observed in systemic autoimmune disorders.[35]

Pathophysiology

Dacryoadenitis results from immune-mediated inflammation, leading to glandular enlargement and dysfunction. In infectious cases, direct microbial invasion triggers an acute inflammatory response characterized by neutrophilic infiltration, tissue swelling, and cytokine-driven immune activation.[36] The ensuing inflammatory cascade obstructs the lacrimal ducts and reduces tear production, causing ocular discomfort and dry eye symptoms.[37] Chronic noninfectious dacryoadenitis is marked by predominant lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltration, leading to progressive fibrosis and glandular shrinkage.[38] The immunopathogenesis varies based on the underlying cause.

In autoimmune-associated dacryoadenitis, such as in Sjögren syndrome cases, autoantibodies and T-cell-mediated inflammation contribute to glandular tissue destruction.[39] In sarcoidosis, granulomatous inflammation alters the lacrimal gland’s structure, progressively impairing function.[40] IgG4-related dacryoadenitis is characterized by extensive lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, storiform fibrosis, and obliterative phlebitis. Elevated serum immunoglobulin 4 (IgG4) levels and histological findings of IgG4-positive plasma cells define this condition.[41] Although its precise pathophysiology remains under investigation, dysregulated immune responses potentially triggered by environmental or genetic factors are thought to contribute to its development.

Histopathology

Nonspecific inflammation of the lacrimal gland can exhibit various histopathological patterns. Infiltration may consist primarily of lymphocytes or a mixture of lymphocytes and neutrophils. The inflammatory cells' distribution pattern may be focal, diffuse, or perivascular. Fibrosis and acinar destruction may also be present. In cases associated with sarcoidosis, nonnecrotizing granulomas composed of epithelioid and multinucleated giant cells may be observed. IgG4-related dacryoadenitis features lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and may develop interlobular fibrosis.[42] Immunohistochemical staining can reveal an increased number of IgG4-positive plasma cells.[43]

Histopathological analysis is crucial for differentiating various forms of dacryoadenitis and guiding treatment decisions. Acute infectious dacryoadenitis typically presents with neutrophilic infiltration, glandular swelling, and localized necrosis. Bacterial dacryoadenitis is often characterized by abscess formation and polymorphonuclear leukocyte infiltration, whereas viral infections generally result in lymphocytic infiltration, sometimes accompanied by plasma cells.[44]

Chronic dacryoadenitis, particularly when linked to autoimmune disorders such as Sjögren syndrome, IgG4-RD, and sarcoidosis, demonstrates distinct histological features. Dacryoadenitis associated with Sjögren syndrome is marked by lymphocyte infiltration, germinal center formation, acinar destruction, and periductal fibrosis.[45] IgG4-related dacryoadenitis is defined by dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, storiform fibrosis, and obliterative phlebitis.[46] A diagnosis is supported when IgG4-positive plasma cells constitute more than 40% of the total plasma cell population.[47]

History and Physical

Acute dacryoadenitis commonly presents with erythema and tenderness over the superotemporal orbit. The glandular enlargement causes the lateral eyelid to droop, producing a characteristic S-shaped curve along the eyelid margin (see Image. Typical Dacryoadenitis).[48][49][48] Suppurative discharge from the lacrimal ducts, pouting of the lacrimal ductules, conjunctival chemosis, and swelling of preauricular and cervical lymph nodes may also be observed.[50] Fever and malaise can accompany these findings.[51] Inflammatory dacryoadenitis often develops more gradually, typically presenting as painless lacrimal gland swelling, which may be bilateral.[52]

A thorough history and physical examination are essential for diagnosing dacryoadenitis. A recent viral or bacterial infection may suggest an infectious cause.[53] Chronic dacryoadenitis may present as a progressively enlarging, painless gland, often with symptoms indicative of an underlying systemic disorder.[54][55] The physical examination should assess for eyelid edema, palpate the lacrimal gland for tenderness and consistency, and evaluate conjunctival injection and chemosis. Signs of orbital involvement, including proptosis, restricted extraocular motility, and vision impairment, require further evaluation to exclude orbital cellulitis or malignancy.[56] Bilateral dacryoadenitis raises suspicion for autoimmune or systemic inflammatory conditions, such as Sjögren syndrome, sarcoidosis, or IgG4-RD.[57]

Evaluation

Acute lacrimal gland swelling associated with a viral illness does not require biopsy or extensive laboratory evaluation. However, an additional workup is warranted if atypical features are present or if the swelling persists despite treatment.[58] Bilateral involvement, systemic symptoms, or occurrence in older adults raises suspicion for malignancy or an underlying autoimmune condition, necessitating further investigation.

Laboratory tests for identifying the cause of dacryoadenitis may include a complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, anti-nuclear antibody, and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody. Angiotensin-converting enzyme is an unreliable marker for sarcoidosis. Serological tests for anti-Ro/SSA, anti-La/SSB, and IgG4 levels are important in diagnosing systemic inflammatory disorders. Infectious evaluation may include viral serologies, blood cultures, and tuberculosis testing.[59]

Imaging studies play a vital role in evaluating lacrimal gland involvement and distinguishing inflammatory conditions from neoplastic processes. Ultrasound may be used to assess glandular hypertrophy and internal echotexture.[60] Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provide detailed visualization of soft tissue involvement, osseous erosion, and orbital extension.[61] Contrast-enhanced MRI is particularly effective in differentiating benign inflammatory conditions from malignancy.[62] In acute dacryoadenitis, imaging may reveal adjacent lateral rectus myositis, periscleritis, or scleritis.[63] Chronic inflammatory conditions do not typically exhibit scleral enhancement.

Lacrimal gland biopsy is indicated in cases with atypical features, unclear etiology, or inadequate response to treatment.[64] In a review of 60 cases of lacrimal gland inflammation of unknown origin, histopathologic analysis identified a specific diagnosis in 61.7%, with 38% linked to systemic disease. Systemic steroids should be avoided before biopsy when feasible, as they can alter histologic findings. A biopsy is typically conducted using a transcutaneous approach, targeting the orbital lobe while preserving the tear ducts that drain through the palpebral lobe into the temporal conjunctival fornix.[65] Tissue samples are typically fixed in formalin, while fresh tissue is required for flow cytometry. Coordination with the laboratory before biopsy is essential, as specific handling and transport requirements may vary, particularly for flow cytometry.

Treatment / Management

The treatment of dacryoadenitis depends on its underlying cause. Acute viral dacryoadenitis usually resolves within 4 to 6 weeks and may require only supportive care, including analgesics and warm compresses. If a chalazion or signs of bacterial infection are present, topical antibiotics with warm compresses may be beneficial. The efficacy of oral antiviral therapy remains uncertain.

Bacterial dacryoadenitis necessitates systemic antibiotic therapy, with coverage for methicillin-resistant S aureus being advisable.[66] Broad-spectrum antibiotics such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, rifampin, doxycycline, or vancomycin may be considered. In cases of purulent discharge, obtaining cultures can help guide antibiotic selection.[67](B3)

Fungal dacryoadenitis requires systemic antifungal therapy and, in some cases, surgical debridement.[68] Abscess formation may warrant surgical drainage.[69] A lacrimal gland biopsy should be performed following appropriate imaging if the glandular enlargement persists beyond 3 months despite treatment, an abscess develops, glandular atrophy occurs, or malignancy is suspected.[70][71]

Corticosteroids reduce lacrimal gland swelling in nearly all forms of dacryoadenitis, making a steroid trial for diagnostic purposes unwarranted. One study suggests that idiopathic dacryoadenitis may respond well to surgical debulking with a low relapse rate.[72] Corticosteroids remain the primary treatment for noninfectious dacryoadenitis. Autoimmune-associated dacryoadenitis, such as that seen in Sjögren syndrome or sarcoidosis, may require systemic immunosuppressive therapy. The management of IgG4-related dacryoadenitis remains under discussion, but an initial trial of corticosteroids is reasonable, with immunosuppressive therapy rarely necessary.(B2)

Reports indicate that sclerosing dacryoadenitis associated with IgG4-related disease may progress to lymphoma.[73] Refractory inflammatory dacryoadenitis may benefit from orbital radiotherapy, methotrexate, or rituximab. Although IgG4-related disease has a high remission rate with rituximab, the response may be temporary.[74] An interprofessional approach involving ophthalmologists, rheumatologists, and infectious disease specialists is essential for optimizing patient outcomes.(B2)

Differential Diagnosis

Malignancy must be ruled out when focal swelling of the lacrimal gland occurs with a gradual onset, particularly in an older patient. Lymphomatous lesions can infiltrate the lacrimal gland.[75] These conditions exist on a spectrum ranging from reactive lymphoid hyperplasia to atypical lymphoid hyperplasia and malignant lymphoma. Both benign and malignant lymphoid tumors cause diffuse enlargement of the lacrimal lobes on imaging.[76] Epithelial tumors of the lacrimal gland may present similarly, including benign mixed tumors, adenoid cystic carcinoma, mixed malignant carcinoma, and mucoepidermoid carcinoma.[77]

Malignant metastases in this region are rare. However, when present, breast cancer is the most common primary source, spreading via lymphatic or hematogenous routes. Among the causes of lacrimal gland enlargement, approximately 50% are due to infection or inflammation, 25% are from lymphoid tumors, and 25% are due to salivary tumors.[78] Histopathological analysis remains the definitive method for distinguishing inflammatory from neoplastic processes.

Thyroid eye disease can sometimes mimic dacryoadenitis, presenting with diplopia due to restrictive inflammation of the extraocular muscles.[79] Unlike dacryoadenitis, thyroid eye disease typically causes lid retraction rather than mild ptosis.[80] Other infectious conditions, such as preseptal or orbital cellulitis, should be considered when evaluating periorbital swelling, erythema, and pain.[81] Focal swelling of the upper eyelid may also result from a chalazion or hordeolum, neither of which involves true lacrimal gland enlargement.[82]

Staging

Dacryoadenitis is not typically classified using a formal staging system. The extent and severity of the disease are assessed based on clinical presentation and imaging findings. Acute dacryoadenitis is categorized as mild, moderate, or severe based on symptoms such as discomfort, erythema, and associated orbital involvement. Chronic dacryoadenitis is classified by the degree of fibrosis and functional impairment of the lacrimal gland. In IgG4-related dacryoadenitis, the severity is evaluated using the IgG4-RD Responder Index, which considers the number of affected organs, disease burden, and therapeutic response.[83] Determining disease severity is crucial for guiding treatment decisions and monitoring disease progression.

Prognosis

The prognosis of dacryoadenitis depends on its underlying cause and the timeliness of treatment. Acute bacterial dacryoadenitis generally has a favorable outcome with prompt antibiotic therapy, often resolving within days to weeks. Viral dacryoadenitis is typically self-limiting, with full recovery expected in most cases. While infectious dacryoadenitis may necessitate antibiotics, it usually resolves without long-term complications.

Chronic and autoimmune forms, such as those associated with Sjögren syndrome, sarcoidosis, or IgG4-RD, may lead to persistent inflammation, fibrosis, and lacrimal gland dysfunction.[84] In severe cases, these complications may result in significant dry eye disease, negatively impacting quality of life.[85] Inflammatory dacryoadenitis tends to be more refractory to treatment and is influenced by any underlying systemic condition. Management may require prolonged steroid tapering, chronic immunomodulatory therapy, or surgical debulking.

As with any nonspecific orbital inflammation, recurrence or lack of resolution warrants a biopsy or repeat biopsy. Early diagnosis and appropriate immunosuppressive therapy can help prevent long-term complications.

Complications

Complications from infectious dacryoadenitis are uncommon, but a lacrimal gland abscess may form, or the infection may progress to preseptal or orbital cellulitis.[86] If left untreated, severe dacryoadenitis can have ocular and systemic consequences. In bacterial infections, abscess formation may necessitate surgical drainage. Orbital cellulitis and its spread to adjacent structures can result in vision-threatening complications, including optic neuropathy and cavernous sinus thrombosis.

Chronic inflammatory dacryoadenitis may lead to progressive fibrosis of the lacrimal gland, causing permanent gland dysfunction and persistent dry eye symptoms. Individuals with IgG4-RD or sarcoidosis may experience multisystem involvement, often requiring prolonged immunosuppressive therapy.[87]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education is crucial for preventing and managing dacryoadenitis. Proper hygiene and prompt treatment of upper respiratory infections can reduce the risk of infectious dacryoadenitis. Patients should be counseled that infectious dacryoadenitis typically resolves on its own but may require antibiotics.

Monitoring for vision changes, pain with eye movement, or suppuration is important for identifying complications such as orbital cellulitis or abscess formation. When dacryoadenitis is linked to an autoimmune condition, patients should be educated about the disease, potential systemic involvement, and the possible need for an extended steroid taper or long-term immunomodulatory therapy.

Pearls and Other Issues

Dacryoadenitis can arise from viral, autoimmune, or idiopathic origins, requiring a comprehensive evaluation to ascertain the underlying etiology. Bilateral lacrimal gland involvement often suggests an autoimmune disorder, whereas unilateral acute cases are more commonly infectious. Imaging and biopsy are essential for distinguishing dacryoadenitis from neoplastic conditions such as lymphoma. Corticosteroids remain the primary treatment for noninfectious dacryoadenitis, though targeted biological therapy is emerging as an alternative for refractory cases.[88]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing dacryoadenitis requires an interprofessional approach involving ophthalmologists, rheumatologists, infectious disease specialists, and radiologists. Effective interprofessional communication ensures accurate diagnosis and timely intervention, reducing the risk of complications. Since dacryoadenitis is an uncommon condition, collaboration among healthcare providers facilitates appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Surgery may be necessary in select cases to obtain a lacrimal gland biopsy for diagnostic purposes.

For inflammatory dacryoadenitis that recurs after steroid tapering, consultation with a rheumatologist to assess the need for immunomodulatory therapy is often beneficial. Coordination with rheumatology and internal medicine is also recommended when extraocular symptoms suggest a systemic disease. An interprofessional team approach involving plastic specialty-certified nurses and specialist physicians for evaluation and follow-up supports optimal outcomes. Ongoing research into the molecular mechanisms of dacryoadenitis and the development of targeted therapies may further refine treatment strategies. Interprofessional collaboration and patient education remain key to improving the management and prognosis of dacryoadenitis.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Singh S, Selva D. Non-infectious Dacryoadenitis. Survey of ophthalmology. 2022 Mar-Apr:67(2):353-368. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2021.05.011. Epub 2021 May 31 [PubMed PMID: 34081929]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMombaerts I. The many facets of dacryoadenitis. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2015 Jul:26(5):399-407. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000183. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26247137]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMaehara T, Pillai S, Stone JH, Nakamura S. Clinical features and mechanistic insights regarding IgG4-related dacryoadenitis and sialoadenitis: a review. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2019 Jul:48(7):908-916. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2019.01.006. Epub 2019 Jan 25 [PubMed PMID: 30686634]

Chan J, Biddle K, Green A, Batista C, D'Cruz D. IgG4-related disease causing dacryoadenitis, bronchial stenosis and lobar collapse. BMJ case reports. 2025 Feb 13:18(2):. pii: e262905. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2024-262905. Epub 2025 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 39947723]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLi F, Zhu X, Zhu Z, Li N. Minimally Invasive Management of Infantile Dacryocystitis with Lacrimal Abscess: A Case Report. The American journal of case reports. 2025 Feb 11:26():e946588. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.946588. Epub 2025 Feb 11 [PubMed PMID: 39930691]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePietris J, Quigley C, Lam L, Selva D. Bacterial Dacryoadenitis With Abscess: Meta-Analysis of Features and Outcomes of a Rare Clinical Entity. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2025 Feb 13:():. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000002924. Epub 2025 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 39945355]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRodrigues G, Hiran H, Suprasanna K, Mendonca T, Suresh J. Ptosis and dacryoadenitis following COVID. Clinical & experimental optometry. 2024 Jul:107(5):584-586. doi: 10.1080/08164622.2023.2197580. Epub 2023 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 37078169]

Yazıcıoğlu T, Ağaçkesen A, Adıgüzel Karaoysal Ö. Anatomical factors behind acquired primary nasolacrimal duct obstruction and acute dacryocystitis. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2025 Apr:282(4):2135-2140. doi: 10.1007/s00405-024-09193-9. Epub 2025 Jan 5 [PubMed PMID: 39757266]

Vahdani K, Luthert PJ, Rose GE. Chronic Granulomatous Dacryoadenitis Associated With Pleomorphic Adenoma. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2022 Mar-Apr 01:38(2):e54-e57. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000002096. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34812181]

Soong CN, Stewart S, White S, Curragh D. Acute suppurative bacterial dacryoadenitis with abscess formation in a child. Canadian journal of ophthalmology. Journal canadien d'ophtalmologie. 2022 Dec:57(6):e218-e219. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2022.05.001. Epub 2022 May 24 [PubMed PMID: 35623409]

Lam J, Eleff T, Pelowski AM. Chronic bilateral dacryoadenitis with concurrent tattoo inflammation following COVID-19 vaccination and infection. Clinical & experimental optometry. 2024 Nov:107(8):860-862. doi: 10.1080/08164622.2023.2257205. Epub 2023 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 37751621]

Ogul H, Nisa Unlu E. Bilateral dacryoadenitis associated with IgG4-related disease presenting as orbital pseudo-inflammatory tumor. Joint bone spine. 2022 Nov:89(6):105440. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2022.105440. Epub 2022 Aug 3 [PubMed PMID: 35933087]

Mafee MF, Haik BG. Lacrimal gland and fossa lesions: role of computed tomography. Radiologic clinics of North America. 1987 Jul:25(4):767-79 [PubMed PMID: 3299475]

Tan CH, Tauchi-Nishi PS, Sweeney AR. Atypical presentation of bilateral Epstein-Barr virus dacryoadenitis: a case report of corticosteroid resistant orbital inflammation. Journal of ophthalmic inflammation and infection. 2023 May 12:13(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s12348-023-00349-y. Epub 2023 May 12 [PubMed PMID: 37173558]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAmjadi S, Rajak S, Solanki H, Selva D. Dacryoadenitis associated with adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 2016 Mar:44(2):140-2. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12637. Epub 2015 Dec 10 [PubMed PMID: 26302257]

Takahashi Y, Vaidya A, Kono S, Yokoyama T, Kakizaki H. Epidemic Keratoconjunctivitis-Associated Acute Dacryoadenitis in an Adult. Cureus. 2022 Jul:14(7):e27003. doi: 10.7759/cureus.27003. Epub 2022 Jul 19 [PubMed PMID: 35989856]

Ataei Y, Boal NS, Esmaili N. Herpes Simplex Virus Dacryoadenitis Preceding Skin Vesicles. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2024 Sep-Oct 01:40(5):e150-e152. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000002652. Epub 2024 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 38722786]

Rhem MN, Wilhelmus KR, Jones DB. Epstein-Barr virus dacryoadenitis. American journal of ophthalmology. 2000 Mar:129(3):372-5 [PubMed PMID: 10704555]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDossantos J, Goldstein SM. Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus With Dacryoadenitis Complicated by Recurrent Orbital Inflammation. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2023 Nov-Dec 01:39(6):e204-e206. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000002471. Epub 2023 Jul 21 [PubMed PMID: 37486336]

Nanayakkara U, Khan MA, Hargun DK, Sivagnanam S, Samarawickrama C. Ocular streptococcal infections: A clinical and microbiological review. Survey of ophthalmology. 2023 Jul-Aug:68(4):678-696. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2023.02.001. Epub 2023 Feb 9 [PubMed PMID: 36764397]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChi YC, Lin CC, Chiu TY. Microbiology and Antimicrobial Susceptibility in Adult Dacryocystitis. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2024:18():575-582. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S452707. Epub 2024 Feb 23 [PubMed PMID: 38414483]

Rodríguez-Lozano J, Armiñanzas Castillo C, Ruiz de Alegría Puig C, Ventosa Ayarza JA, Fariñas MC, Agüero J, Calvo J. Post-traumatic endophthalmitis caused by Nocardia nova. JMM case reports. 2019 Feb:6(2):e005175. doi: 10.1099/jmmcr.0.005175. Epub 2019 Feb 20 [PubMed PMID: 30886723]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAcharya I, Basa D, Kavitha M. First case report of isolated aspergillus dacryoadenitis. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2016 Jun:64(6):462-4. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.187678. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27488157]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTian X, Sun H, Huang Y, Sui W, Zhang D, Sun Y, Jin J, He Y, Lu X. Microbiological isolates and associated complications of dacryocystitis and canaliculitis in a prominent tertiary ophthalmic teaching hospital in northern China. BMC ophthalmology. 2024 Feb 5:24(1):56. doi: 10.1186/s12886-024-03323-x. Epub 2024 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 38317063]

Madge SN, Prabhakaran VC, Shome D, Kim U, Honavar S, Selva D. Orbital tuberculosis: a review of the literature. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2008:27(4):267-77. doi: 10.1080/01676830802225152. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18716964]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePowers HR, Diaz MA, Mendez JC. Tuberculosis presenting as dacryoadenitis in the USA. BMJ case reports. 2019 Nov 19:12(11):. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-231694. Epub 2019 Nov 19 [PubMed PMID: 31748361]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCarrão DL, Hernandez JMF, Cardoso JD, Correia TR, Araújo JL, Ubiali DG. Dacryoadenitis caused by Cochliomyia macellaria (Diptera: Calliphoridae) in a sambar deer (Rusa unicolor) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Veterinary parasitology, regional studies and reports. 2021 Jan:23():100504. doi: 10.1016/j.vprsr.2020.100504. Epub 2020 Dec 3 [PubMed PMID: 33678361]

Ang T, Tong JY, Patel S, Selva D. Differentiation of bacterial orbital cellulitis and diffuse non-specific orbital inflammation on magnetic resonance imaging. European journal of ophthalmology. 2025 Mar:35(2):727-733. doi: 10.1177/11206721241272227. Epub 2024 Sep 2 [PubMed PMID: 39223841]

Yeşiltaş YS, Gündüz AK. Idiopathic Orbital Inflammation: Review of Literature and New Advances. Middle East African journal of ophthalmology. 2018 Apr-Jun:25(2):71-80. doi: 10.4103/meajo.MEAJO_44_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30122852]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMombaerts I, Rose GE, Garrity JA. Orbital inflammation: Biopsy first. Survey of ophthalmology. 2016 Sep-Oct:61(5):664-9. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2016.03.002. Epub 2016 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 26994870]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAndrew NH, Sladden N, Kearney DJ, Selva D. An analysis of IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD) among idiopathic orbital inflammations and benign lymphoid hyperplasias using two consensus-based diagnostic criteria for IgG4-RD. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2015 Mar:99(3):376-81. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-305545. Epub 2014 Sep 2 [PubMed PMID: 25185258]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDeschamps R, Deschamps L, Depaz R, Coffin-Pichonnet S, Belange G, Jacomet PV, Vignal C, Benillouche P, Herdan ML, Putterman M, Couvelard A, Gout O, Galatoire O. High prevalence of IgG4-related lymphoplasmacytic infiltrative disorder in 25 patients with orbital inflammation: a retrospective case series. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2013 Aug:97(8):999-1004. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-303131. Epub 2013 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 23759440]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAli MJ. Pediatric Acute Dacryocystitis. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2015 Sep-Oct:31(5):341-7. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000472. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25856337]

Hoffmann J, Lipsett S. Acute Dacryocystitis. The New England journal of medicine. 2018 Aug 2:379(5):474. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm1713250. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30067930]

Luemsamran P, Rootman J, White VA, Nassiri N, Heran MKS. The role of biopsy in lacrimal gland inflammation: A clinicopathologic study. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2017 Dec:36(6):411-418. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2017.1352608. Epub 2017 Aug 17 [PubMed PMID: 28816552]

Baudouin C, Irkeç M, Messmer EM, Benítez-Del-Castillo JM, Bonini S, Figueiredo FC, Geerling G, Labetoulle M, Lemp M, Rolando M, Van Setten G, Aragona P, ODISSEY European Consensus Group Members. Clinical impact of inflammation in dry eye disease: proceedings of the ODISSEY group meeting. Acta ophthalmologica. 2018 Mar:96(2):111-119. doi: 10.1111/aos.13436. Epub 2017 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 28390092]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceXue K, Ren H, Liu A, Qian J. Changes in Tear Film Characteristics in Patients With Idiopathic Dacryoadenitis. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2017 Jan/Feb:33(1):31-34. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000628. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26863039]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBaybora H, Uysal HH, Baykal O, Karabela Y. Investigating Estrogen and Progesterone Receptors in the Lacrimal Sacs of Individuals With and Without Chronic Dacryocystitis. Beyoglu eye journal. 2019:4(1):38-41. doi: 10.14744/bej.2019.35744. Epub 2019 Apr 16 [PubMed PMID: 35187430]

Zhao X, Li N, Yang N, Mi B, Dang W, Sun D, Ma S, Nian H, Wei R. Thymosin β4 Alleviates Autoimmune Dacryoadenitis via Suppressing Th17 Cell Response. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2023 Aug 1:64(11):3. doi: 10.1167/iovs.64.11.3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37531112]

Roca M, Moro G, Broseta R, Roca B. Sarcoidosis presenting with acute dacryoadenitis. Postgraduate medicine. 2018 Mar:130(2):284-286. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2018.1418141. Epub 2017 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 29257721]

Yazici B, Onaran Z, Yalcinkaya U. IgG4-Related Dacryoadenitis With Fibrous Mass in a 19-Month-Old Child: Case Report and Literature Review. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2024 Nov-Dec 01:40(6):e202-e205. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000002717. Epub 2024 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 39136975]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcNab AA, McKelvie P. IgG4-Related Ophthalmic Disease. Part II: Clinical Aspects. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2015 May-Jun:31(3):167-78. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000364. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25564258]

Go H, Kim JE, Kim YA, Chung HK, Khwarg SI, Kim CW, Jeon YK. Ocular adnexal IgG4-related disease: comparative analysis with mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma and other chronic inflammatory conditions. Histopathology. 2012 Jan:60(2):296-312. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.04089.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22211288]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHayano S, Nakada N, Kashima M. Acute Dacryoadenitis due to Primary Epstein-Barr Virus Infection. Open forum infectious diseases. 2022 Apr:9(4):ofac086. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac086. Epub 2022 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 35355892]

Guo X, Dang W, Li N, Wang Y, Sun D, Nian H, Wei R. PPAR-α Agonist Fenofibrate Ameliorates Sjögren Syndrome-Like Dacryoadenitis by Modulating Th1/Th17 and Treg Cell Responses in NOD Mice. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2022 Jun 1:63(6):12. doi: 10.1167/iovs.63.6.12. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35687344]

Mai Thanh C, Nguyen Thi K, Nguyen Canh H, Nguyen Thi Dieu T. Pediatric IgG4-related dacryoadenitis and sialadenitis (Mikulicz's disease) with acquired hemophilia A: A case report and review of literature. International journal of immunopathology and pharmacology. 2024 Jan-Dec:38():3946320241301734. doi: 10.1177/03946320241301734. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39605254]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKanda M, Nagahata K, Moriyama M, Takano KI, Kamekura R, Yoshifuji H, Tsuboi H, Yamamoto M, Umehara H, Umeda M, Sakamoto M, Maehara T, Inoue Y, Kubo S, Himi T, Origuchi T, Masaki Y, Mimori T, Dobashi H, Tanaka Y, Nakamura S, Takahashi H. The 2023 revised diagnostic criteria for IgG4-related dacryoadenitis and sialadenitis. Modern rheumatology. 2024 Oct 23:():. pii: roae096. doi: 10.1093/mr/roae096. Epub 2024 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 39441008]

Takase R, Hagiya H, Tokumasu K, Nishimura Y, Sakurai A, Hasegawa K, Hanayama Y, Otsuka F. Droopy eyelid due to IgG4-related dacryoadenitis. Postgraduate medical journal. 2021 May:97(1147):333-334. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-138416. Epub 2020 Aug 11 [PubMed PMID: 32788315]

Hung YC, Wang DD, Han LSM, Betts TD, Weatherhead RG. SLE dacryoadenitis. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2019 Aug:38(4):338-341. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2018.1518463. Epub 2018 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 30541377]

Boualila L,Bouirig K,Tagmouti A,Boutimzine N,Cherkaoui LO,Bouanane R,Touarsa F,Jiddane M,Alloul N,El Ouanass M, Acute suppurative bacterial dacryoadenitis (ASBD) in a child: A rare pseudomonal etiology. Journal francais d [PubMed PMID: 37620191]

Abumanhal M, Leibovitch I, Zisapel M, Eviatar T, Edel Y, Ben Cnaan R. Ocular and orbital manifestations in VEXAS syndrome. Eye (London, England). 2024 Jun:38(9):1748-1754. doi: 10.1038/s41433-024-03014-3. Epub 2024 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 38548942]

Williams KJ, Allen RC. Paediatric orbital and periorbital infections. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2019 Sep:30(5):349-355. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000589. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31261188]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAlmater AI, Malaikah RH, Alzahrani S, Al-Faky YH. Presumed acute suppurative bacterial dacryoadenitis with concurrent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 infection. Saudi journal of ophthalmology : official journal of the Saudi Ophthalmological Society. 2021 Jul-Sep:35(3):266-268. doi: 10.4103/SJOPT.SJOPT_277_21. Epub 2022 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 35601851]

Solbes-Gochicoa MM, Shoji MK, Chen JS, Al-Sharif E, Kikkawa DO, Korn BS, Liu CY. Chronic dacryocystitis due to Mycobacterium abscessus. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2024 Oct 15:():1-6. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2024.2412121. Epub 2024 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 39405041]

Sáenz González AF, Busquet I Duran N, Arámbulo O, Badal Alter JM. Chronic dacryocystitis caused by sarcoidosis. Archivos de la Sociedad Espanola de Oftalmologia. 2019 Apr:94(4):188-191. doi: 10.1016/j.oftal.2018.10.010. Epub 2018 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 30558969]

Ronquillo Y, Zeppieri M, Patel BC. Nonspecific Orbital Inflammation. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31869057]

Danesh K, Cohen LM, Liu Y, Karlin JN, Rootman DB. Systemic eosinophilic disease presenting as dacryoadenitis. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2023 Feb:42(1):107-111. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2021.1973514. Epub 2021 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 34514933]

Zhou HW, Tran AQ, Tooley AA, Miyauchi JT, Kazim M. Atypical Cogan Syndrome Featuring Orbital Myositis and Dacryoadenitis. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2021 May-Jun 01:37(3S):S160-S162. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001835. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32991499]

Li N, Gao Z, Zhao L, Du B, Ma B, Nian H, Wei R. MSC-Derived Small Extracellular Vesicles Attenuate Autoimmune Dacryoadenitis by Promoting M2 Macrophage Polarization and Inducing Tregs via miR-100-5p. Frontiers in immunology. 2022:13():888949. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.888949. Epub 2022 Jul 6 [PubMed PMID: 35874782]

Komori T, Inoue D, Izumozaki A, Sugiura T, Terada K, Yoneda N, Toshima F, Yoshida K, Kitao A, Kozaka K, Takahira M, Kawano M, Kobayashi S, Gabata T. Ultrasonography of IgG4-related dacryoadenitis and sialadenitis: Imaging features and clinical usefulness. Modern rheumatology. 2022 Aug 20:32(5):986-993. doi: 10.1093/mr/roab063. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34918161]

Abdel Razek AA. Imaging of connective tissue diseases of the head and neck. The neuroradiology journal. 2016 Jun:29(3):222-30. doi: 10.1177/1971400916639605. Epub 2016 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 26988082]

Sengor T, Yuzbasioglu E, Aydın Kurna S, Irkec M, Altun A, Kökcen K, Yalcin NG. Dacryoadenitis and extraocular muscle inflammation associated with contact lens-related Acanthamoeba keratitis: A case report and review of the literature. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2017 Feb:36(1):43-47. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2016.1243132. Epub 2016 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 27874294]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAndrew NH, Kearney D, Sladden N, McKelvie P, Wu A, Sun MT, McNab A, Selva D. Idiopathic Dacryoadenitis: Clinical Features, Histopathology, and Treatment Outcomes. American journal of ophthalmology. 2016 Mar:163():148-153.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.11.032. Epub 2015 Dec 15 [PubMed PMID: 26701269]

Takano K, Okuni T, Yamamoto K, Kamekura R, Yajima R, Yamamoto M, Takahashi H, Himi T. Potential utility of core needle biopsy in the diagnosis of IgG4-related dacryoadenitis and sialadenitis. Modern rheumatology. 2019 Mar:29(2):393-396. doi: 10.1080/14397595.2018.1465665. Epub 2018 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 29656682]

Sakamoto M, Moriyama M, Shimizu M, Chinju A, Mochizuki K, Munemura R, Ohyama K, Maehara T, Ogata K, Ohta M, Yamauchi M, Ishiguro N, Matsumura M, Ohyama Y, Kiyoshima T, Nakamura S. The diagnostic utility of submandibular gland sonography and labial salivary gland biopsy in IgG4-related dacryoadenitis and sialadenitis: Its potential application to the diagnostic criteria. Modern rheumatology. 2020 Mar:30(2):379-384. doi: 10.1080/14397595.2019.1576271. Epub 2019 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 30696319]

O'Callaghan RJ. The Pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus Eye Infections. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland). 2018 Jan 10:7(1):. doi: 10.3390/pathogens7010009. Epub 2018 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 29320451]

Wai KM, Locascio JJ, Wolkow N. Bacterial dacryoadenitis: clinical features, microbiology, and management of 45 cases, with a recent uptick in incidence. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2022 Oct:41(5):563-571. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2021.1966813. Epub 2021 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 34455901]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSimmons BA, Kupcha AC, Law JJ, Wang K, Carter KD, Mawn LA, Shriver EM. Misdiagnosis of fungal infections of the orbit. Canadian journal of ophthalmology. Journal canadien d'ophtalmologie. 2023 Oct:58(5):449-454. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2022.04.007. Epub 2022 May 4 [PubMed PMID: 35525264]

Garrity JA. Not a Tumor-Nonspecific Orbital Inflammation. Journal of neurological surgery. Part B, Skull base. 2021 Feb:82(1):96-99. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1722636. Epub 2021 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 33777622]

Rose GE. A personal view: probability in medicine, levels of (Un)certainty, and the diagnosis of orbital disease (with particular reference to orbital "pseudotumor"). Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2007 Dec:125(12):1711-2 [PubMed PMID: 18071128]

Kaushik M, Vahdani K, Neumann I, Magan T, Rose GE. Repeated Lacrimal Gland Biopsies. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2024 Jul-Aug 01:40(4):440-444. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000002614. Epub 2024 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 38329425]

Mombaerts I, Cameron JD, Chanlalit W, Garrity JA. Surgical debulking for idiopathic dacryoadenitis: a diagnosis and a cure. Ophthalmology. 2014 Feb:121(2):603-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.09.010. Epub 2013 Oct 25 [PubMed PMID: 24572677]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCheuk W, Yuen HK, Chan AC, Shih LY, Kuo TT, Ma MW, Lo YF, Chan WK, Chan JK. Ocular adnexal lymphoma associated with IgG4+ chronic sclerosing dacryoadenitis: a previously undescribed complication of IgG4-related sclerosing disease. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2008 Aug:32(8):1159-67. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31816148ad. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18580683]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceEbbo M, Patient M, Grados A, Groh M, Desblaches J, Hachulla E, Saadoun D, Audia S, Rigolet A, Terrier B, Perlat A, Guillaud C, Renou F, Bernit E, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Harlé JR, Schleinitz N. Ophthalmic manifestations in IgG4-related disease: Clinical presentation and response to treatment in a French case-series. Medicine. 2017 Mar:96(10):e6205. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006205. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28272212]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGuo J, Qian J, Zhang R. The pathological features of ectopic lymphoid neogenesis in idiopathic dacryoadenitis. BMC ophthalmology. 2016 May 26:16():66. doi: 10.1186/s12886-016-0250-0. Epub 2016 May 26 [PubMed PMID: 27230507]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSchittkowski MP, Storch MW. [Diseases of the Lacrimal Gland]. Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde. 2020 May:237(5):703-723. doi: 10.1055/a-1068-7699. Epub 2020 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 32016935]

Gündüz AK, Yeşiltaş YS, Shields CL. Overview of benign and malignant lacrimal gland tumors. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2018 Sep:29(5):458-468. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000515. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30028745]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGao Y, Moonis G, Cunnane ME, Eisenberg RL. Lacrimal gland masses. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2013 Sep:201(3):W371-81. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9553. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23971467]

Ishikawa E, Takahashi Y, Valencia MRP, Ana-Magadia MG, Kakizaki H. Asymmetric lacrimal gland enlargement: an indicator for detection of pathological entities other than thyroid eye disease. Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 2019 Feb:257(2):405-411. doi: 10.1007/s00417-018-4197-0. Epub 2018 Nov 28 [PubMed PMID: 30488266]

Shieh WS, Huggins AB, Rabinowitz MR, Rosen MR, Rabinowitz MP. A case of concurrent silent sinus syndrome, thyroid eye disease, idiopathic orbital inflammatory syndrome, and dacryoadenitis. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2017 Dec:36(6):462-464. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2017.1337194. Epub 2017 Aug 16 [PubMed PMID: 28812921]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFoo VHX, Teh GH. Gonococcal dacryoadenitis complicated by orbital cellulitis: a case report. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2025 Feb:44(1):114-116. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2024.2351517. Epub 2024 May 26 [PubMed PMID: 38796782]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAlsalamah AK, Alkatan HM, Al-Faky YH. Acute dacryocystitis complicated by orbital cellulitis and loss of vision: A case report and review of the literature. International journal of surgery case reports. 2018:50():130-134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.07.045. Epub 2018 Aug 9 [PubMed PMID: 30118963]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKanda M, Kamekura R, Sugawara M, Nagahata K, Suzuki C, Takano K, Takahashi H. IgG4-related disease administered dupilumab: case series and review of the literature. RMD open. 2023 Mar:9(1):. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2023-003026. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36894196]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePerugino CA, Stone JH. IgG4-related disease: an update on pathophysiology and implications for clinical care. Nature reviews. Rheumatology. 2020 Dec:16(12):702-714. doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-0500-7. Epub 2020 Sep 16 [PubMed PMID: 32939060]

Yamaguchi T. Inflammatory Response in Dry Eye. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2018 Nov 1:59(14):DES192-DES199. doi: 10.1167/iovs.17-23651. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30481826]

Jyani R, Ranade D, Joshi P. Spectrum of Orbital Cellulitis on Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Cureus. 2020 Aug 11:12(8):e9663. doi: 10.7759/cureus.9663. Epub 2020 Aug 11 [PubMed PMID: 32923259]

Vasilyev VI, Safonova TN, Socol EV, Probatova NA, Kokosadze NV, Pavlovskaya AI, Kovrigina AM, Radenska-Lopovok SG, Gorodetsky VR, Rodionova EB, Palshina SG, Aleksandrova EN, Shornikova NS, Gaiduk IV. Diagnosis of IgG4 - related ophthalmic disease in a group of patients with various lesions of the eye and orbits. Terapevticheskii arkhiv. 2018 May 11:90(5):61-71. doi: 10.26442/terarkh201890561-71. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30701891]

Al-Ghazzawi K, Neumann I, Knetsch M, Chen Y, Wilde B, Bechrakis NE, Eckstein A, Oeverhaus M. Treatment Outcomes of Patients with Orbital Inflammatory Diseases: Should Steroids Still Be the First Choice? Journal of clinical medicine. 2024 Jul 9:13(14):. doi: 10.3390/jcm13143998. Epub 2024 Jul 9 [PubMed PMID: 39064038]