Introduction

Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis (IGH) is a benign, typically asymptomatic leukodermic dermatosis of unclear etiology, classically seen in older adults with fair skin, and often goes unrecognized or undiagnosed.[1] Occasionally, IGH is aesthetically displeasing. However, this condition is not dangerous. Once present, lesions do not remit. Treatment aims to improve cosmesis.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of IGH remains unknown. Proposed theories suggest it may result from the skin's natural aging process, cumulative chronic sun exposure, or repeated microtrauma.[2] However, none of these hypotheses have been confirmed.

Epidemiology

IGH occurs in all races and skin types but is more common in fair-skinned individuals. The condition may also affect darker skin types, and lesions may be more noticeable in such patients. Women's heightened perception of cosmetic concerns may have contributed to the previous belief that IGH is more common in this patient group. However, recent studies indicate equal prevalence between the sexes. Regardless of sex, prevalence and incidence increase with age. IGH may appear in young adults in their 20s and 30s, but a recent study found that 87% of individuals aged 40 and older had at least 1 lesion, while up to 80% of people older than 70 are affected.

Pathophysiology

Given its extremely high overall incidence, the pathogenesis of IGH appears complex, likely involving both genetic and environmental factors. Many studies highlight sun exposure as a central factor, though a definitive causal relationship remains unproven. Interestingly, lesions are uncommon on the face and neck—typical sites for other actinic processes—suggesting a multifactorial pathophysiology.

Small studies have reported a higher prevalence of these lesions among relatives of patients with IGH compared to controls, implying at least a partial hereditary component. A recent study supported this theory, noting a statistically significant increase in IGH incidence among renal transplant patients with the human leukocyte antigen DQ3 haplotype and a negative association with the human leukocyte antigen DR8 haplotype.[3]

Histopathologic findings have been inconsistent in identifying underlying mechanisms. Some studies attribute IGH to a reduction in melanocyte numbers, while others suggest structural abnormalities, such as fewer melanosomes, decreased dendrites, reduced tyrosinase activity, or defective keratinocyte uptake rather than a melanocytic process.[4] Additionally, some studies propose a role for senescent fibroblasts in IGH development.[5]

Histopathology

As diagnosis is typically based on history and physical examination alone, histopathologic evaluation of IGH lesions is usually unnecessary. If a biopsy is performed, pathology findings classically show a reduced number of epidermal melanocytes containing 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA) within the basal layer, though not completely absent as in vitiligo. Furthermore, melanin pigmentation is decreased, best appreciated when compared with the adjacent normal epidermis, as isolated lesions without neighboring normal tissue may be difficult to assess.

Other histologic features include flattening of rete ridges, with or without epidermal atrophy. Epidermal atrophy is more commonly observed in non-sun-exposed areas. Orthokeratosis, either in a "basket-weave" pattern or as compact orthokeratosis, may be present in the stratum corneum.

Electron microscopy findings suggest melanocyte degeneration, characterized by a dilated endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial swelling. A decrease in melanosomes and dendrites has also been observed, contrasting with vitiligo, where dendritic processes are increased.[6][7]

History and Physical

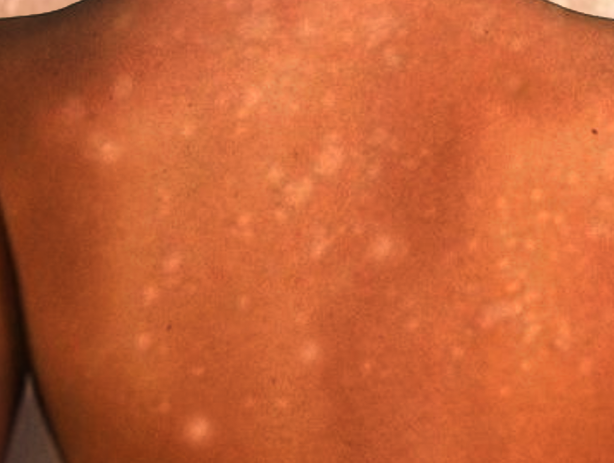

IGH presents as multiple small, scattered, discrete, round or oval, achromic or hypochromic macules, typically 2 to 6 mm in size, that develop gradually over the years (see Image. Guttate Hypomelanosis). Occasionally, larger lesions up to 2.5 cm appear. Lesions are usually smooth, though scaly and hyperkeratotic variants have been reported.[8]

Patterns or groupings do not form, and lesions remain stable in size without regression. Adnexal structures, including hair follicles, appear unaffected, with hairs within lesions retaining their pigment. IGH occurs most commonly in sun-exposed areas, particularly the dorsal upper and lower extremities, with a preference for distal over proximal sites. However, sun-protected areas, including the trunk and, rarely, the face, may also be affected.

Evaluation

Given the benign course of IGH, laboratory, radiographic, or other diagnostic tests are typically unnecessary. However, dermoscopy can be a valuable tool for evaluating IGH lesions. This assessment can reveal the following distinct morphological patterns, listed in order of incidence:

- Amoeboid: Pseudopod-like extensions

- Feathery: Irregular pigmentation with feathery margins and a whitish central area

- Petaloid: Polycyclic margins resembling flower petals

- Nebuloid: Indistinct, smudged borders

The nebulous pattern appears more frequently in early lesions, while amoeboid, feathery, and petaloid patterns are more common in older lesions.[9]

Treatment / Management

Patients should be reassured that IGH lesions are benign and do not require treatment. No universally accepted, effective therapies exist for this condition. However, since sunlight is likely a contributing or even precipitating factor, all patients should use sunscreens and physical barriers.

Several treatments have shown variable success, alone or in combination, in improving the condition cosmetically. These treatments include cryotherapy, superficial abrasion, topical steroids, topical retinoids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, dermabrasion, topical 88% phenol, fractional carbon dioxide lasers, nonablative fractional photothermolysis with a fractional 1,550-nm ytterbium/erbium fiber laser, and excimer light treatment.[10] More recently, 50% trichloroacetic acid peels have also been used.[11]

Patients should be counseled on the risk of worsening leukoderma with cryotherapy and the potential for long-standing, though not permanent, erythema and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation with treatments such as fractional carbon dioxide lasers. Promising studies suggest that combining fractional photothermolysis with topical calcineurin inhibitors may enhance outcomes. More recently, research has noted increased melanocyte presence following microneedling combined with microinfusion of 5-fluorouracil via a tattoo machine, presenting a potential treatment option.[12][13][14](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of guttate leukoderma is broad, as similar lesions appear in various generalized dyschromatoses. Distinguishing IGH from vitiligo early in the disease course is crucial since IGH lesions remain stable, whereas vitiligo progresses. Other common dermatologic conditions in the differential diagnosis include pityriasis versicolor, pityriasis alba, café au lait macules, lichen sclerosus, guttate morphea, and post-inflammatory hypopigmentation. Each condition has a characteristic distribution and associated findings.

Less commonly considered but important differential diagnoses include achromic verruca plana, pityriasis lichenoides chronica, disseminated hypopigmented keratoses following psoralen and ultraviolet A (PUVA) therapy, clear cell papulosis, and atrophie blanche. Achromic verruca plana lesions are more susceptible to koebnerization and, histologically, exhibit koilocytes. Pityriasis lichenoides chronica presents with more widespread lesions accompanied by an overlying scale. Disseminated hypopigmented keratoses develop after psoralen and ultraviolet A therapy, appearing as well-demarcated, small, hypopigmented, flat-topped papules uniformly distributed on the trunk and extremities. Histologic findings include variable acanthosis, orthokeratosis or parakeratosis, papillomatosis, and a normal amount of melanin and melanocytes.

Clear cell papulosis, a rare condition in young children, primarily affects the face and trunk and may follow "milk lines." Lesions consist of multiple hypopigmented, barely elevated, small, flat-topped papules and macules. Histologically, large clear cells in the basal layer display an immunohistochemical staining pattern similar to Toker clear cells of the nipple and extramammary Paget disease.

Both IGH and atrophie blanche favor the distal dorsal extremities, such as the dorsal shins. However, atrophie blanche lesions typically arise at sites of previous ulcers, feature more angulated margins, and appear as porcelain-white, depressed atrophic scars with a surrounding rim of telangiectasia.[15]

Prognosis

IGH is a benign condition with an excellent prognosis. However, once present, lesions do not remit without treatment. As such, IGH primarily represents a cosmetic concern. The condition may be an indication of cumulative sun exposure. However, no direct correlation has been made to date.

Complications

While complications are rare, IGH may have cosmetic and psychological effects, especially in individuals with darker skin tones, as contrast with surrounding pigmentation in the skin of these patients is more noticeable. Persistent lesions can cause distress and reduce quality of life, particularly for individuals concerned with aesthetic appearance. Additionally, differentiating IGH from more serious conditions such as vitiligo, post-inflammatory hypopigmentation, and leukoderma-associated malignancies may lead to unnecessary biopsies or interventions. Although generally stable, an increasing number or size of lesions over time can heighten psychosocial concerns, emphasizing the need for patient reassurance and, in some cases, dermatologic intervention.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Deterrence of IGH primarily involves photoprotection, as chronic UV exposure is a significant contributing factor. Patients should be advised regarding the regular use of broad-spectrum sunscreens, protective clothing, and sun avoidance during peak hours to minimize lesion progression. Although IGH is benign and asymptomatic, patient education should focus on differentiating it from more concerning pigmentary disorders, such as vitiligo or post-inflammatory hypopigmentation, to alleviate unnecessary anxiety.

Individuals seeking cosmetic improvement may be counseled on available treatment options, including topical retinoids, fractional laser therapy, and superficial chemical peels, even though the efficacy of these modalities varies. Reassurance regarding the benign nature of IGH is essential, particularly for patients experiencing psychosocial distress due to significantly contrasting skin pigmentation.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Recognizing IGH helps prevent unnecessary treatments. The interprofessional team includes primary care providers, dermatologists, and specialty-trained nurses. Uncertain diagnoses should be referred to dermatology, and dermatology nurses play a key role in patient education.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Falabella R, Escobar C, Giraldo N, Rovetto P, Gil J, Barona MI, Acosta F, Alzate A. On the pathogenesis of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1987 Jan:16(1 Pt 1):35-44 [PubMed PMID: 3805391]

Shin MK, Jeong KH, Oh IH, Choe BK, Lee MH. Clinical features of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis in 646 subjects and association with other aspects of photoaging. International journal of dermatology. 2011 Jul:50(7):798-805. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04743.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21699514]

Arrunategui A, Trujillo RA, Marulanda MP, Sandoval F, Wagner A, Alzate A, Falabella R. HLA-DQ3 is associated with idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis, whereas HLA-DR8 is not, in a group of renal transplant patients. International journal of dermatology. 2002 Nov:41(11):744-7 [PubMed PMID: 12452995]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKim SK, Kim EH, Kang HY, Lee ES, Sohn S, Kim YC. Comprehensive understanding of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: clinical and histopathological correlation. International journal of dermatology. 2010 Feb:49(2):162-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04209.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20465639]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKim JY, Lee SH, Ahn Y, Lee EJ, Park MY, Hwang S, Almurayshid A, Lim BJ, Oh SH. Role of senescent fibroblasts in the development of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. The British journal of dermatology. 2020 Jun:182(6):1481-1482. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18801. Epub 2020 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 31823346]

Kakepis M, Havaki S, Katoulis A, Katsambas A, Stavrianeas N, Troupis TG. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: an electron microscopy study. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2015 Jul:29(7):1435-8. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12646. Epub 2014 Aug 4 [PubMed PMID: 25088925]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKim TH, Park H, Baek DJ, Kang HY. Melanocytes in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis disappear and are senescent. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2023 Apr:37(4):e565-e567. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18757. Epub 2022 Nov 25 [PubMed PMID: 36394380]

Buch J, Patil A, Kroumpouzos G, Kassir M, Galadari H, Gold MH, Goldman MP, Grabbe S, Goldust M. Idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: Presentation and Management. Journal of cosmetic and laser therapy : official publication of the European Society for Laser Dermatology. 2021 Feb 17:23(1-2):8-15. doi: 10.1080/14764172.2021.1957116. Epub 2021 Jul 25 [PubMed PMID: 34304679]

Reddy AM, Banti S, Nataraj S, Rajesh G, Konappalli S. The correlation between dermoscopic patterns and histopathological features in idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis at a tertiary care center. Acta dermatovenerologica Alpina, Pannonica, et Adriatica. 2024 Sep:33(3):119-124 [PubMed PMID: 39324349]

Kreeshan FC, Madan V. Idiopathic Guttate Hypomelanosis Treated with 308-nm Excimer Light and Topical Bimatoprost. Journal of cutaneous and aesthetic surgery. 2021 Jan-Mar:14(1):115-117. doi: 10.4103/JCAS.JCAS_112_20. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34084020]

Vedamurthy M, Vanasekar P, Raghupathy S. Use of 50% trichloroacetic acid in the treatment of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2022 Jan:86(1):e11-e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.110. Epub 2020 Apr 29 [PubMed PMID: 32360719]

Rambhia SH, Rambhia KD. Treatment of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis with 5-fluorouracil tattooing using a handheld needle. JAAD international. 2020 Dec:1(2):200-201. doi: 10.1016/j.jdin.2020.09.002. Epub 2020 Nov 3 [PubMed PMID: 34409340]

Arbache S, de Mendonça MT, Arbache ST, Hirata SH. Treatment of idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis with a tattoo device versus a handheld needle. JAAD international. 2021 Jun:3():14-16. doi: 10.1016/j.jdin.2021.01.005. Epub 2021 Mar 6 [PubMed PMID: 34409366]

Arbache S, Hirata SH. Efficacy and Safety of 5-Fluorouracil Tattooing to Repigment Idiopathic Guttate Hypomelanosis: A Split-Body Randomized Trial. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2023 Jun 1:49(6):603-608. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000003793. Epub 2023 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 37011024]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceArbache S, Michalany NS, de Almeida HL Jr, Hirata SH. Unveiling idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis: pathology, immunohistochemistry, and ultrastructural study. International journal of dermatology. 2022 Aug:61(8):995-1002. doi: 10.1111/ijd.16076. Epub 2022 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 35114009]