Introduction

An M-plasty is an excisional technique used to remove standing cutaneous deformities, also known as dog ears, from the end of a linear wound repair. Dog ears arise from the redundant gathering of tissue when overly obtuse angles (>30 degrees) are used at the ends of surgical excisions. Many different techniques address dog ears. The primary nonexcisional technique involves distributing the excess skin on 1 side of the incision evenly relative to the other side by placing sutures at wider intervals on the longer side of the incision compared to the shorter side, thereby balancing tension across the wound. This approach may not work in all situations and is dependent upon the degree of tissue redundancy and overall wound length. For example, this technique will have a limited impact on short incisions or large dog ears. The most commonly employed surgical option to remove a dog ear is direct excision of the excess tissue. A triangular piece of tissue, known as a Burow triangle, can be removed anywhere along the length of the incision. Typically, a Burow triangle is taken at the end of the incision, increasing the scar's final length.[1]

An M-plasty is an alternative to this technique and offers the additional benefit of reducing the final scar length while conserving adjacent normal tissue.[2] In some cases, an M-plasty may be employed at the end of an incision to avoid extending the scar across an aesthetic subunit boundary or disrupting an otherwise intact anatomical structure, albeit at the cost of introducing a bifurcated (forked) configuration to the wound termination. This trade-off may, in certain cases, negatively affect the cosmetic acceptability of the final result.[3][4]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Aesthetically, the face is divided up into several subunits: forehead, brows, orbits, nose, cheeks, mouth, chin, and ears, each of which has its constituent parts with additional boundaries among them. Keeping scars within a single subunit or, preferably, between subunits can substantially improve cosmetic results. In these situations, using an M-plasty to redirect or terminate the scar along subunit boundaries can be very helpful. Additionally, many facial anatomical structures possess free or mobile margins—such as the nasal alae, auricular helices, eyebrows, hairline, and eyelids—where incision placement should be carefully planned to avoid cicatricial notching and functional distortion. M-plasties can be very useful in these cases as well.[4][5][6][7]

Indications

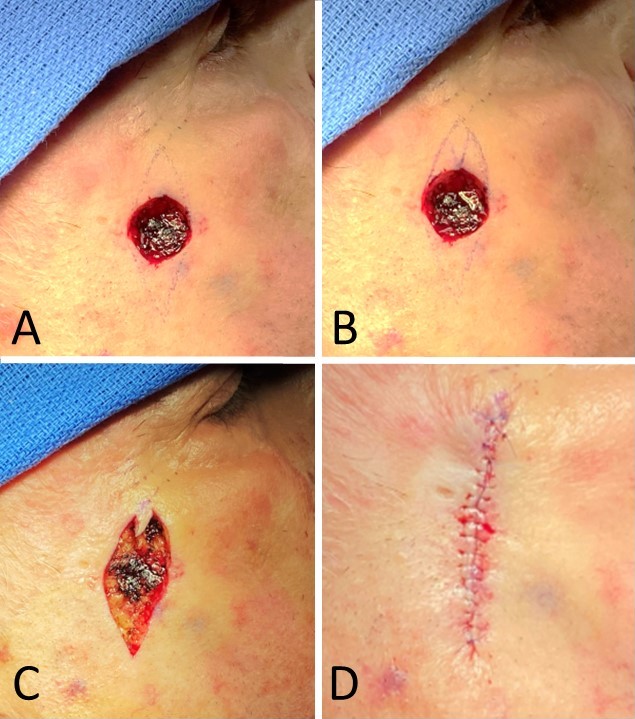

An M-plasty is useful for shortening the excision's expected final scar length.[8][9][10] This can be beneficial when longer incisions are contraindicated to avoid crossing cosmetic boundaries or extending into sensitive structures. For example, an M-plasty can be used near the lateral canthus to remove a dog ear without distorting the corner of the eye. This location is particularly well-suited for M-plasty, as the resulting scar may be concealed within natural rhytides, such as crow’s feet (see Image. M-Plasty Technique). The M-plasty technique applies in the glabellar region when complete fusiform excision extends the scar into the medial canthi. Still, an M-plasty can branch the incisions into the superior and inferior eyelid subunits.[11] While M-plasty is typically employed in the closure of wounds resulting from the excision of skin lesions, it is also helpful in the closure of full-thickness skin graft donor site defects, where tissue conservation is important.[12]

Additionally, an M-plasty may remove dog ears created by flaps. M-plasties can be added to either 1 or both ends of an incision to shorten a wound. Although M-plasties decrease the length of a scar, they increase its width by adding a fork to the end. This trade-off may be cosmetically favorable, particularly in areas where scar camouflage is achievable. For example, large tumors on the back may be less noticeable with an M-plasty on each end compared to a longer, straight repair. The main goal of the M-plasty is to take an excision that would otherwise extend across cosmetic unit boundaries and keep the incision within a single unit. Last, the M-plasty has also been described for the orientation of pathological specimens, an application that may optimize tissue preservation and reduce suture usage while maintaining directional accuracy.[13]

Contraindications

Notably, a traditional M-plasty, unlike a Z-plasty, does not alter tension vectors. For this reason, the contraindications for M-plasty are the same as those for primary linear closures. M-plasty is contraindicated in wounds where excessive tension would compromise the reliable approximation of wound edges. Attempting closure may lead to mechanical dehiscence and/or ischemic necrosis due to stretching and compression of the microvasculature within the subdermal plexus. Increased tension can also lead to poor cosmetic outcomes, including widened or irregular scars, sometimes called “fish-mouth” deformities. More importantly, excessive closure tension near anatomically sensitive regions—such as eyelids, eyebrows, nasal alae, auricles, or lips—may distort these structures, impairing function and appearance.

Equipment

The required equipment will vary depending on the size, depth, and anatomic location of the wound. However, in general, the following instruments are commonly used for performing an M-plasty:

- Skin marker

- Superficial (epidermal) sutures

- Deep dermal or subcutaneous sutures

- Needle driver

- Adson or toothed forceps

- Suture scissors

- #15 blade scalpel

- Electrocautery device or other hemostatic equipment

- Dissecting scissors, such as Metzenbaum or Kaye blepharoplasty scissors

Personnel

This procedure can be performed by the surgeon alone. However, an assistant can be quite helpful and improve the procedure's efficiency. If excision of a skin lesion causes a defect that requires an M-plasty for closure, a pathologist may be necessary. Anesthesia and nursing requirements will depend on the size, depth, and anatomic location of the lesion, as well as the patient's overall condition and procedural setting.

Preparation

Cutaneous surgery can be performed in an office setting. The use of sterile versus nonsterile gloves may be determined at the surgeon’s discretion, as the risk of surgical site infection in minor dermatologic procedures is low, particularly for procedures on the face, where the vascular supply and immune response are robust. The skin should be prepped with an appropriate antiseptic solution, selected based on the surgical site and surgeon's preference.[14][15]

Patient Counseling

The surgeon should provide preoperative counseling regarding the procedure's risks, including infection, bleeding, scarring, and possible lesion recurrence. The patient should also receive a clear explanation of the surgical steps and expected outcomes. Visual aids, such as diagrams or annotated photographs of the lesion and planned excision pattern, may enhance patient understanding and facilitate informed consent. These illustrations can also help demonstrate the anticipated appearance of the closure following the procedure. When cosmetically sensitive areas—such as the face—are involved, the patient should be counseled on the potential for dissatisfaction with the scar’s final appearance. Postoperative scar care should be emphasized, including photoprotection. Scars in cosmetically prominent areas should be shielded from sun exposure for up to 12 months postoperatively to minimize dyspigmentation and optimize aesthetic outcomes.[16]

Technique or Treatment

An M-plasty may be designed before excision or later in the repair process. The design is best visualized by first drawing out a fusiform excision. To add an M-plasty to 1 end of the excision, the peak of the planned excision is inverted or folded inward on itself to create an "M" (see figure) with 30-degree angles at and between the tips of the M. Tips with angles substantially greater than 30 degrees may result in additional standing cutaneous dog ear deformities. Take care not to make the M so deep that it intrudes on the lesion itself and compromises the oncological integrity of the resection, if applicable.

Preferably, the excision margins around the lesion are drawn first, and then the overlay of the planned M-plasty is drawn. The skin is incised in the standard fashion. Undermining is performed in the appropriate plane depending on the body location, which is generally subdermal. The final configuration of an M-plasty is a "Y," with the base representing the linear closure and the arms of the "Y" representing the M-plasty. Sutures may be placed in either a running or an interrupted fashion and will often be placed in layers, depending on the depth and location of the excision. The tip of the M-plasty may benefit from a tip stitch to align the tissue properly.[9][17]

If an M-plasty removes a dog ear, the dog ear is elevated with forceps. Then, 2 incisions are made at 45-degree angles from the main incision on either side of the dog ear, and Burow triangles are removed. This creates a "Y"-shaped closure. The excess tissue is removed from the sides of the incision, sparing the "V" created between the 2 new incisions. The wound is then closed in the same fashion as above.

Nested M-Plasty

A nested M-plasty is a variant of a traditional M-plasty and can be described as an M-plasty within an M-plasty. If a standard M-plasty shortens the length of the scar and preserves healthy tissue, performing the process twice produces even shorter scars and preserves even more tissue, albeit at the expense of a more complicated procedure and a complex, branched scar. A standard M-plasty can be visualized as an ellipse with the peak of the ellipse folded inward. This produces 2 side-by-side triangles that are half the width of the original peak. A nested M-plasty repeats this process within 1 or both of those triangles. The triangles are folded on themselves again, creating 4 side-by-side triangles that are one-quarter the original width, resulting in a branching appearance (see Image. Stages of an M-Plasty). As with a regular M-plasty, tip stitches can be useful for this closure type. This technique is best used on flat or concave surfaces as it can induce skin bunching, which typically flattens out with time. Bunching of skin over convex surfaces can be quite noticeable and tends to persist; it should, therefore, be avoided via meticulous incision design and closure.[18]

M-Plasty Modifications

The modified M-plasty, described by Asken in 1986, uses a shortened ellipse with obtuse angles and places additional tangential incisions on opposite sides of the ellipse at either end of the wound. The closure is accomplished with local undermining and adjustment of tension vectors; the final scar is Y-shaped, like a traditional M-plasty, but shorter still.[19] Another variant of the M-plasty modifies the angle of divergence between the 2 triangles such that they exceed 30 degrees, and the bases of the triangles remain separated by a distance equal to the maximum width of the ellipse. Using this technique, the compressive forces that bunch up the skin begin to subside, and the M-plasty takes on some of the tension-altering characteristics of a V to Y advancement closure.[20]

Complications

Complications associated with M-plasty are similar to those observed with other primary wound closure techniques. In addition to pain, bleeding, infection, and the potential need for revision surgery, there remains the possibility of cosmetically suboptimal scarring. Patients may find that the bifurcated nature of the final scar is noticeable, or the scar itself may ultimately become widened, hypertrophic, atrophic, hyperpigmented, hypopigmented, or erythematous. Poor scar design, suboptimal execution, or delayed wound healing can lead to persistent standing cutaneous deformities.

Management strategies for unsightly scarring may include:

- Topical therapies, such as silicone gel sheeting or depigmenting agents like hydroquinone

- Laser resurfacing, using ablative or nonablative fractional devices, particularly for texture and color irregularities

- Intense pulsed light (IPL) treatment for persistent erythema

- Microneedling, chemical peels, or intralesional corticosteroids in selected cases

- Surgical scar revision for refractory or anatomically distorted scars

Photoprotection remains essential throughout remodeling to prevent dyspigmentation, particularly in individuals with Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI.[21][22]

Clinical Significance

The M-plasty is a versatile, tissue-conserving technique that permits primary wound closure while limiting the total incision length. In addition to optimizing scar orientation, the technique can also be used to remove standing cutaneous deformities such as dog ears without significantly extending the final scar. Every cutaneous surgeon should be proficient in the design, planning, and execution of M-plasty closures to achieve both functional and aesthetic surgical outcomes.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective execution of M-plasty requires not only surgical skill but also coordinated interprofessional collaboration to optimize patient outcomes, safety, and satisfaction. Surgeons and advanced practitioners must be proficient in selecting appropriate candidates for M-plasty, recognizing ideal anatomic locations, and tailoring the design to minimize tension and preserve functional and cosmetic outcomes. Nurses are vital in pre and postoperative education, wound care, and monitoring for complications such as infection or dehiscence. Communication between all care team members ensures proper timing of dressing changes, suture removal, and pain control, all of which are crucial for optimal healing and patient-centered recovery.

Incorporating pharmacists into the care team enhances patient safety through proper medication reconciliation, allergy screening, and postoperative analgesia planning. Wound care specialists may assist with dressing selection and long-term scar management, while physical or occupational therapists may be involved when incisions are near joints or functionally sensitive areas. Interprofessional communication and shared decision-making ensure alignment in treatment goals and patient preferences, ultimately improving satisfaction and reducing complications. Coordinated follow-up and documentation help maintain continuity of care, making M-plasty a successful and safe reconstructive technique when delivered through a collaborative healthcare model.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Depending on the location of the wound, nurses may be responsible for suture removal approximately 7 to 14 days postoperatively. When procedures are performed in cosmetically sensitive areas, such as the face, nursing staff should also educate patients on the importance of protecting the healing wound from ultraviolet exposure, which can contribute to dyspigmentation and hypertrophic scarring. Patients should be advised to keep the wound covered or apply a broad-spectrum sunscreen with a minimum sun protection factor of 30 outdoors. Photoprotection should be maintained consistently until the scar matures, typically over 12 months.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Postoperative nursing and allied healthcare team monitoring should include regular assessment of wound healing, signs of infection, and early identification of complications such as dehiscence or hypertrophic scarring. Patient adherence to wound care protocols and photoprotection should also be reinforced during follow-up visits to optimize functional and cosmetic outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

M-Plasty Technique. The M-plasty closes basal cell carcinoma resection defect inferolateral to the eye. This technique was used at the superomedial end of the incision to hide it in the crow's feet rhytides. A) Defect with standard fusiform excision and closure planned. B) The defect with M-plasty is planned at the superomedial end. C) M-plasty and inferolateral Burow's triangle excised. D) The incision is closed, with the final shape in the form of the letter Y.

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS

References

Dzubow LM. The dynamics of dog-ear formation and correction. The Journal of dermatologic surgery and oncology. 1985 Jul:11(7):722-8 [PubMed PMID: 4008741]

Meybodi F, Pham M, Sedaghat N, Elder E, French J. The Modified M-plasty Approach to Mastectomy: Avoiding the Lateral Dog-ear. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Global open. 2022 Feb:10(2):e4116. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000004116. Epub 2022 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 35198347]

Garg S, Dahiya N, Gupta S. Surgical scar revision: an overview. Journal of cutaneous and aesthetic surgery. 2014 Jan:7(1):3-13. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.129959. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24761092]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKirwan L. Aesthetic Units and Zones of Adherence: Relevance to Surgical Planning in the Head and Neck. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Global open. 2023 Aug:11(8):e5186. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000005186. Epub 2023 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 37583395]

Field LM. The combination of a cheek advancement-rotation flap with an M-plasty for upper preauricular excisions. The Journal of dermatologic surgery and oncology. 1985 Oct:11(10):974-6 [PubMed PMID: 4044981]

Field LM. Hairline reconstruction utilizing modified winged V-plastic hair-bearing flaps and focal anastomotic line excisions. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 1996 Nov:22(11):937-40 [PubMed PMID: 9063509]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMishra B, Mallik S, Agnihotry I, Behera J. Aesthetic Reconstruction Based on Facial Subunit Principle for Basal Cell Carcinoma of the Face: A Retrospective Analysis. Cureus. 2024 Mar:16(3):e56826. doi: 10.7759/cureus.56826. Epub 2024 Mar 24 [PubMed PMID: 38654794]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWeisberg NK, Nehal KS, Zide BM. Dog-ears: a review. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2000 Apr:26(4):363-70 [PubMed PMID: 10759826]

Webster RC, Davidson TM, Smith RC, Kitchens GG, Clairmont AA, Schwartzenfeld TH, Smith RR, White BJ Jr, Bush J, Cook TA, Johnson CM, White MF. M-plasty techniques. The Journal of dermatologic surgery. 1976 Nov:2(5):393-6 [PubMed PMID: 993442]

Modica LA, Leicht SS. M-plasty for large cheek defects. American family physician. 1987 Jan:35(1):123-4 [PubMed PMID: 3799414]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCamacho FM, García-Hernandez MJ, Pérez-Bernal AM. M-plasty in the treatment of carcinomas located on the interglabellar region. European journal of dermatology : EJD. 1998 Dec:8(8):548-50 [PubMed PMID: 9889425]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDaichi M, Fumio O, Nobuhiro S. M-plasty for Full-Thickness Skin Graft Donor Site. Eplasty. 2015:15():ic54 [PubMed PMID: 26483862]

Swanson NA, Tromovitch TA, Stegman SJ, Glogau RG. The M-plasty as a means of orienting a surgical specimen for the pathologist. The Journal of dermatologic surgery and oncology. 1980 Sep:6(9):706-7 [PubMed PMID: 6999047]

Xia Y, Cho S, Greenway HT, Zelac DE, Kelley B. Infection rates of wound repairs during Mohs micrographic surgery using sterile versus nonsterile gloves: a prospective randomized pilot study. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2011 May:37(5):651-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.01949.x. Epub 2011 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 21457390]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRhinehart MB, Murphy MM, Farley MF, Albertini JG. Sterile versus nonsterile gloves during Mohs micrographic surgery: infection rate is not affected. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2006 Feb:32(2):170-6 [PubMed PMID: 16442035]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAleisa A, Veldhuizen IJ, Rossi AM, Nehal KS, Lee EH. Patient Education on Scarring Following Mohs Micrographic Surgery: Patient Preference for Information Delivery. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2022 Nov 1:48(11):1155-1158. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000003557. Epub 2022 Aug 23 [PubMed PMID: 36342247]

Salasche SJ, Roberts LC. Dog-ear correction by M-plasty. The Journal of dermatologic surgery and oncology. 1984 Jun:10(6):478-82 [PubMed PMID: 6373868]

Krishnan RS, Donnelly HB. The nested M-plasty for scar length shortening. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2008 Sep:34(9):1236-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34265.x. Epub 2008 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 18554292]

Asken S. A modified M-plasty. The Journal of dermatologic surgery and oncology. 1986 Apr:12(4):369-73 [PubMed PMID: 3514717]

Wisco OJ, Wentzell JM. When an M is a V: vector analysis calls for redesign of the M-plasty. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2009 Aug:35(8):1271-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01223.x. Epub 2009 May 15 [PubMed PMID: 19469795]

Skochdopole A, Dibbs RP, Sarrami SM, Dempsey RF. Scar Revisions. Seminars in plastic surgery. 2021 May:35(2):130-138. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1727291. Epub 2021 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 34121948]

Tullington JE, Gemma R. Scar Revision. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31194458]