Introduction

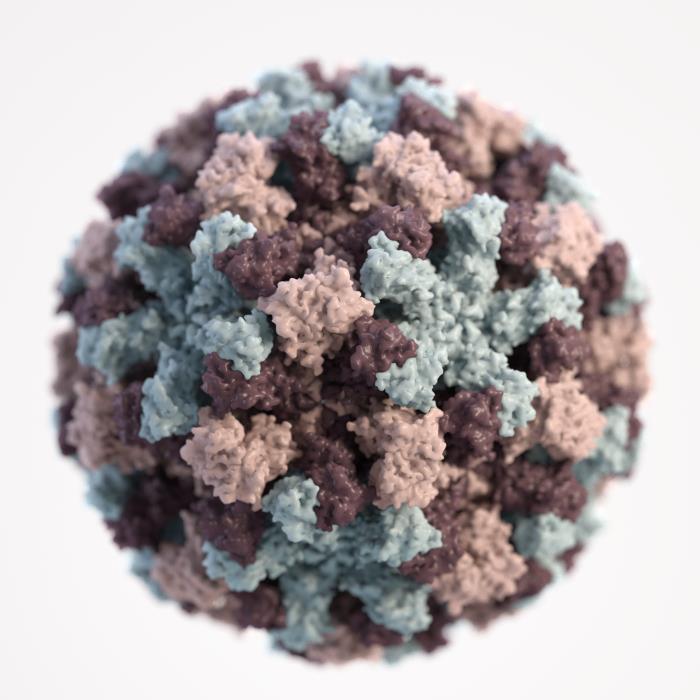

Noroviruses are nonenveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses belonging to the Caliciviridae viral family (see Image. Norovirus Virion). The virus was first identified and named “Norwalk virus” when it was discovered as the cause of a 1968 outbreak of gastroenteritis in Norwalk, Ohio. Norovirus is the leading cause of acute gastrointestinal illness worldwide. In developed countries with rotavirus vaccine programs, norovirus surpasses rotavirus as the most common cause of gastroenteritis in children.

Common symptoms of norovirus infection include nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. These could lead to clinically significant dehydration, requiring hospitalizations. In addition to its clinical effects, norovirus also has a major financial impact on developed nations.[1][2] As of December 2024, there has been a significant surge in norovirus-associated gastroenteritis in the United States and other regions worldwide.[3][CDC NoroSTAT Data]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Norovirus Genotypes

Noroviruses have 10 known genogroups and 49 genotypes. The classification into genogroups and genotypes is based on amino acid diversity in VP1 and ORF1 proteins. Human infections are predominantly due to genogroups GI, GII, and GIV, with GII being the most common cause of gastroenteritis. A minimal number of cases are attributed to GIV. While both genogroups I and II are clinically relevant, a specific strain from genogroup II, norovirus GII.4, has been responsible for the majority of human outbreaks over the preceding 12 years. However, a different GII variant appears to be contributing to recent outbreaks.[4]

As of December 2024, United States surveillance data has identified a significant increase in norovirus-associated gastroenteritis compared with a similar period from previous years.[CDC NoroSTAT Data] The surge in gastroenteritis cases is likely partly due to the emergence of the norovirus strain variant, GII.17.[5] In addition, social distancing during the early years of the COVID-19 pandemic may have decreased exposure to norovirus and thereby reduced background immunity.[6] Studies have shown that waterborne outbreaks tend to be associated with genogroup I strains, while healthcare-related and winter outbreaks are more likely to have genogroup II strains as a causative agent.

The primary mode of transmission of norovirus is fecal-oral. Sources include ingesting contaminated water or food or direct transmission from a contaminated surface or infected person. The virus is resistant and can stay on surfaces even after disinfecting. Norovirus also has a low viral inoculum that causes infection. As few as 10 viral particles are needed to cause infection.[7]

Gastroenteritis Outbreaks

Norovirus outbreaks are common in several different settings. Norovirus is known to cause gastroenteritis outbreaks in hospitals and other healthcare facilities. In addition to healthcare settings, outbreaks may occur in schools, military barracks, cruise ships, and resorts.[8] Person-to-person transmission is the most common mode, but contaminated surfaces also contribute to disease propagation.

Surfaces may be contaminated with viral particles by splashing of emesis or stool or by aerosolized viral particles. Outbreak incidence of norovirus gastroenteritis tends to occur during winter months. Good hand hygiene and effective surface cleaning should be stressed during norovirus outbreaks. Studies suggest that washing hands with soap and running water for at least 20 seconds is the most effective form of hand hygiene for eliminating norovirus. Studies on the effectiveness of alcohol-based hand rubs are inconclusive. Some studies suggest that high-concentration ethanol-based hand sanitizers decrease viral concentration on the hands, but these types of cleaners should be used as a supplement to hand-washing with soap and water. Surfaces such as sinks, toilets, tables, chairs, and beds should be cleaned with a hypochlorite (bleach) solution, and adequate contact time should be ensured. Furthermore, items contaminated with infected emesis or stool that cannot be properly disinfected should be discarded.

Epidemiology

Worldwide, norovirus is responsible for an estimated 685 million cases of gastroenteritis, 150,000 adult deaths, and 50,000 child deaths annually. While lower-income countries bear the greatest disease burden, norovirus infection outbreaks occur worldwide.[9][3] In the United States, approximately 21 million cases of norovirus gastrointestinal illness are diagnosed each year. Because patients with mild disease may not seek medical treatment, the number of cases likely exceeds the estimate. Norovirus is believed to cause approximately 60% of cases of acute gastroenteritis in the United States, and the CDC attributes 400,000 emergency department visits and 71,000 hospitalizations each year to norovirus infection. In a review of reported norovirus outbreaks, food-related transmission was the most common source of widespread disease. Food-related transmission may be due to the ingestion of food that is contaminated during production or the ingestion of food that food service workers contaminated during preparation. High-risk food for norovirus contamination includes foods that are served raw, like fruits and vegetables, as well as oysters and fish.

Although people of all age groups are at risk of contracting norovirus, those at the extremes of age and the immunocompromised are at the highest risk of poor outcomes. Older adults are at increased risk of fatal outcomes, with some studies showing a 30-day mortality rate of 7% for patients with community-acquired norovirus infection. Similarly, neonates have an increased rate of serious complications, eg, necrotizing enterocolitis. Of all age groups, young children have the highest incidence of norovirus. Estimates suggest an annual incidence of norovirus to be 21,400 per 100,000 for children younger than 5. Norovirus infections are also more prevalent in developing nations. Nguyen et al estimated that 17% of reported gastroenteritis cases in developing countries are due to norovirus. Also notable is norovirus’s effects on immunocompromised patients. Patients with compromised immune systems have a higher risk of norovirus infection, higher rates of complications, and increased potential for prolonged asymptomatic viral shedding.[10][11]

Pathophysiology

Noroviruses are difficult to culture in a lab setting, making it difficult to predict how they infect and replicate in humans. Studies suggest that infection is multifaceted and involves multiple cell types in the human gut. The predominant cell type lining the human gut is a single layer of intestinal epithelial cells called enterocytes. Lying deep to the enterocytes are numerous immune cells. Several studies have confirmed that norovirus infects and replicates in immune cells, including macrophages, dendritic cells, and B cells.

Authors have postulated that noroviruses have a way of bypassing enterocytes to enter the human hosts. Proposed mechanisms include entering through M cells, a specialized type of cell in the gut that overlies the Peyer patches and lymphoid follicles in the gut. M cells lack microvilli and do not secrete mucus, making it easier for the norovirus to enter the host and invade immune cells. However, although definitive data are lacking, other studies suggest noroviruses may directly invade enterocytes lining the gut lumen. Furthermore, the role of the host’s preexisting gut microflora in norovirus infection is being investigated. Experts have proposed that norovirus interacts with bacteria in the gut to enhance infection and replication.

The average period from inoculation with the virus until clinical symptoms develop is 1.2 days, and norovirus symptoms usually resolve within 1 to 3 days. Although symptoms may resolve, humans can continue to shed the virus in their stool for extended periods, up to 60 days in some cases. Immunocompromised patients can continue to shed the virus for months or years.[12] The immunologic interaction between humans and norovirus is complex and not well understood.

Host genetic factors appear to play a role in the susceptibility to norovirus, and specific IgG and IgA antibodies develop after infection. The immunologic role of norovirus antigenic diversity remains uncertain, and conflicting data on the duration of immunity has been reported, ranging from a few weeks to several years.[13][14]

History and Physical

Clinical History

The history and physical exam are essential in evaluating all patients with abdominal pain and gastrointestinal symptoms. Patients infected with norovirus typically have symptoms consistent with gastroenteritis. Common symptoms include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and cramping, diarrhea, myalgias, headache, and chills. Some patients report a predominance of diarrhea, while others report nausea and vomiting as primary symptoms. Symptoms may develop with or without prodrome and typically persist for 1 to 3 days.

Essential historical elements to elicit include the patient’s living quarters (eg, nursing home, military barracks), the source of water (eg, river, city, well), recent travel, recent antibiotic use, ingestions of undercooked or raw food, or recent sick contacts (eg, school). Screening for immunocompromised states, which could predict a longer course of symptoms and a greater risk for morbidity and mortality, is also critical.

Physical Examination

Physical exam findings are usually consistent with gastroenteritis. The abdominal exam may reveal nonspecific, nonfocal tenderness, but significant tenderness or peritoneal signs on the abdominal exam should prompt further investigation for other pathology. Likewise, the grossly bloody stool is inconsistent with norovirus infection and warrants further investigation. Patients may show signs of dehydration, eg, tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension, decreased skin turgor, and dry mucous membranes depending on their hydration status. Rarely, patients may present with significant neurologic symptoms such as a seizure or encephalopathy.

Evaluation

Norovirus Evaluation

Many cases of norovirus go undiagnosed, as many patients do not seek medical attention for treatment. For patients seeking evaluation by a clinician, the diagnostic evaluation will be similar to most patients with gastroenteritis. Usually, diagnostic testing is not indicated. A metabolic panel may be warranted for certain patients to assess for electrolyte abnormalities and hydration status. Stool studies such as stool culture, Clostridium difficile toxin, and ova and parasite testing are not usually indicated unless symptoms are prolonged or an alternative pathogen is suspected.

In cases where norovirus is suspected, several enzyme immunoassays and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) are available for the detection of norovirus. Although not usually indicated for individual cases of gastroenteritis, these assays may be useful in detecting norovirus outbreaks. While enzyme immunoassays are the most readily available test, RT-PCR remains the gold standard for detection. Both types of tests use stool or emesis samples to detect GI and GII noroviruses. However, limitations do exist for norovirus testing. Many healthcare facilities do not have access to enzyme immunoassays or RT-PCR, and the sensitivity and specificity of testing are variable. The accuracy of results depends upon the number of samples tested, the timing of stool collection, and proper handling of the sample. Because laboratory testing for norovirus is not uniformly available, clinical evaluation can be useful in detecting norovirus outbreaks. The Kaplan clinical and epidemiological criteria for norovirus were developed before the development of laboratory testing and are still considered useful when definitive testing is unavailable.[15][16][17]

The Kaplan Criteria

If all of the following Kaplan criteria are positive, a norovirus outbreak is highly probable:

- Vomiting in more than half of symptomatic cases

- Mean (or median) incubation period of 24 to 48 hours

- Mean (or median) duration of illness of 12 to 60 hours

- No bacterial pathogen isolated on stool culture

Treatment / Management

The management of norovirus infection involves treating the patient’s symptoms and mitigating the risk of an outbreak. The primary clinical focus should be on the patient’s hydration status, with an emphasis on infection control to prevent the spread of disease to healthcare workers and patient contacts.

Norovirus Management

The mainstay of treatment is oral rehydration therapy. The World Health Organization and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend oral rehydration solutions with electrolytes and glucose. Oral rehydration solutions are preferred over sports drinks and juices for pediatric patients because the latter contains a high carbohydrate and osmotic load that may exacerbate diarrhea.

Patients with intractable vomiting or severe dehydration require intravenous hydration and, possibly, hospital admission. Antibiotics generally are not indicated unless a concern for bacterial infection is present. Antimotility agents have been beneficial in adults, and antiemetics may provide symptomatic relief. Studies support the use of ondansetron in vomiting children, but antimotility agents are not recommended for pediatric patients.

Infection Control Measures

Infection control is a priority in preventing norovirus outbreaks. While efforts at vaccine development are underway, hand hygiene, surface cleaning, and prevention of body fluid exposure are the mainstays of infection control. Currently, hand hygiene is the primary preventive method for outbreaks.[18] Additionally, inpatients should be placed in single occupancy rooms when possible, with contact precautions maintained for at least 48 hours after symptom resolution. If isolation is not feasible, symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals should be separated. Cleaning protocols recommend using bleach-based disinfectants, prioritizing frequently touched surfaces, and moving from less to more contaminated areas.[18] (Please refer to the Etiology section for more information on the prevention of norovirus spread).(B3)

Norovirus Vaccines

Norovirus vaccine development remains a priority for both the perceived public health and economic benefits. Developing a vaccine has been difficult because of the complex nature of norovirus, human immune responses, difficulty culturing the virus, and limited animal models for vaccine testing. Several vaccines are currently in pre-clinical development; one has completed phase 2 adult clinical trials. Due to viral evolution, development efforts have focused on multivalent vaccines similar to influenza vaccines.[19][20][21](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of norovirus includes rotavirus, cholera, Clostridium difficile, Salmonella, Cryptosporidium, Enterovirus, Escherichia coli, Shigella, Campylobacter, and Vibrio infections. Patients presenting with abdominal pain should have the following differentials considered: mesenteric ischemia, abdominal aortic aneurysm, bowel perforation, ectopic pregnancy, appendicitis, cholecystitis, bowel obstruction, diverticulitis, pancreatitis, pyelonephritis, urinary tract infection testicular or ovarian torsion, myocardial infarction, and pelvic inflammatory disease.

Prognosis

While the vast majority of patients experience no significant complications from norovirus infection, over 70,000 hospitalizations and 800 deaths in the United States are attributed to the effects of norovirus each year. Patients at the extremes of age and immunocompromised patients are at the highest risk of adverse outcomes, including death. Specifically, neonatal patients with norovirus infection are at risk for necrotizing enterocolitis, and studies show increased mortality in older adults with norovirus infection. Furthermore, immunocompromised patients are at risk for increased severity and a prolonged clinical course of the illness, with diarrhea lasting months to years in some patients.

Complications

Complications of norovirus include:

- Hypokalemia

- Dehydration

- Hyponatremia

- Metabolic alkalosis

- Renal failure

- Hemolytic uremic syndrome

- Neonatal necrotizing entercolitis

Consultations

Clinicians that may be consulted in the management of norovirus cases include:

- Infectious disease

- Pediatrician

Deterrence and Patient Education

Deterrence and patient education are crucial in preventing norovirus outbreaks and minimizing transmission. Patients and caregivers should be educated on the importance of strict hand hygiene, emphasizing that soap and water are more effective than alcohol-based hand sanitizers in removing the virus. Infection control measures should be reinforced in healthcare and community settings, such as isolating symptomatic individuals and maintaining strict contact precautions for at least 48 hours after symptom resolution. Proper food handling, surface disinfection with bleach-based cleaners, and avoiding contact with infected individuals can further reduce spread. Public awareness and adherence to these preventive strategies are essential.[18]

Pearls and Other Issues

Key factors that should be kept in mind when caring for patients with norovirus include:

- Norovirus is the leading cause of acute gastroenteritis in the United States and worldwide.

- Norovirus is contagious and requires a low inoculum in the host to cause infection. This virus has a short incubation period of approximately 1 to 2 days, and clinical symptoms typically last 1 to 3 days.

- Proper handwashing is important in disease to prevent the spread of disease.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of norovirus requires a coordinated interprofessional approach involving physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals to enhance patient-centered care, safety, and outcomes. Physicians and advanced practitioners play a central role in diagnosing norovirus, assessing patient hydration status, and determining the need for hospital admission. Nurses are essential in patient education, emphasizing the importance of hand hygiene, self-isolation, and infection control measures, particularly for food handlers and caregivers. In outpatient and hospital settings, nurses ensure proper hygiene practices, help monitor symptoms, and assess for complications such as dehydration and electrolyte imbalances. Pharmacists support patient care by advising on rehydration strategies, ensuring patients understand that antibiotics are ineffective against viral infections, and collaborating with prescribers to recommend supportive treatments such as antiemetics when appropriate.

Interprofessional communication and care coordination are crucial in preventing norovirus outbreaks and improving patient outcomes. Epidemiologists and infectious disease specialists contribute by identifying outbreak patterns and guiding public health interventions. Pharmacists and nutritionists work together to ensure patients receive adequate hydration and electrolyte replacement, especially in high-risk populations such as neonates and immunocompromised individuals. Effective communication among team members ensures that infection control measures are properly implemented and that patients receive consistent, evidence-based education. By working collaboratively, healthcare professionals can reduce hospital admissions, minimize transmission risks, and improve overall patient safety and recovery from norovirus infections.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Norovirus Virion. Image of a 3D graphical representation of the Norovirus virion.

JA Allen, Pubic Domain, Public Health Image Library, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

References

Sell J, Dolan B. Common Gastrointestinal Infections. Primary care. 2018 Sep:45(3):519-532. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2018.05.008. Epub 2018 Jul 9 [PubMed PMID: 30115338]

Sadkowska-Todys M, Zieliński A, Czarkowski MP. Infectious diseases in Poland in 2016. Przeglad epidemiologiczny. 2018:72(2):129-141 [PubMed PMID: 30111085]

Bonanno Ferraro G, Brandtner D, Mancini P, Veneri C, Iaconelli M, Suffredini E, La Rosa G. Eight Years of Norovirus Surveillance in Urban Wastewater: Insights from Next-Generation. Viruses. 2025 Jan 17:17(1):. doi: 10.3390/v17010130. Epub 2025 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 39861919]

Chan MC, Lee N, Hung TN, Kwok K, Cheung K, Tin EK, Lai RW, Nelson EA, Leung TF, Chan PK. Rapid emergence and predominance of a broadly recognizing and fast-evolving norovirus GII.17 variant in late 2014. Nature communications. 2015 Dec 2:6():10061. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10061. Epub 2015 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 26625712]

Chhabra P, Wong S, Niendorf S, Lederer I, Vennema H, Faber M, Nisavanh A, Jacobsen S, Williams R, Colgan A, Yandle Z, Garvey P, Al-Hello H, Ambert-Balay K, Barclay L, de Graaf M, Celma C, Breuer J, Vinjé J, Douglas A. Increased circulation of GII.17 noroviruses, six European countries and the United States, 2023 to 2024. Euro surveillance : bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin. 2024 Sep:29(39):. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2024.29.39.2400625. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39328162]

Lappe BL, Wikswo ME, Kambhampati AK, Mirza SA, Tate JE, Kraay ANM, Lopman BA. Predicting norovirus and rotavirus resurgence in the United States following the COVID-19 pandemic: a mathematical modelling study. BMC infectious diseases. 2023 Apr 20:23(1):254. doi: 10.1186/s12879-023-08224-w. Epub 2023 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 37081456]

Atmar RL, Ramani S, Estes MK. Human noroviruses: recent advances in a 50-year history. Current opinion in infectious diseases. 2018 Oct:31(5):422-432. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000476. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30102614]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCrisp CA, Jenkins KA, Dunn I, Kupper A, Johnson J, White S, Moritz ED, Rodriguez LO. Notes from the Field: Cruise Ship Norovirus Outbreak Associated with Person-to-Person Transmission - United States Jurisdiction, January 2023. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2023 Jul 28:72(30):833-834. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7230a5. Epub 2023 Jul 28 [PubMed PMID: 37498798]

Chio CC, Chien JC, Chan HW, Huang HI. Overview of the Trending Enteric Viruses and Their Pathogenesis in Intestinal Epithelial Cell Infection. Biomedicines. 2024 Dec 5:12(12):. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines12122773. Epub 2024 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 39767680]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRandazzo W, D'Souza DH, Sanchez G. Norovirus: The Burden of the Unknown. Advances in food and nutrition research. 2018:86():13-53. doi: 10.1016/bs.afnr.2018.02.005. Epub 2018 May 21 [PubMed PMID: 30077220]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBányai K, Estes MK, Martella V, Parashar UD. Viral gastroenteritis. Lancet (London, England). 2018 Jul 14:392(10142):175-186. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31128-0. Epub 2018 Jun 29 [PubMed PMID: 30025810]

McIntosh EDG. Healthcare-associated infections: potential for prevention through vaccination. Therapeutic advances in vaccines and immunotherapy. 2018 Feb:6(1):19-27. doi: 10.1177/2515135518763183. Epub 2018 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 29998218]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceParrino TA, Schreiber DS, Trier JS, Kapikian AZ, Blacklow NR. Clinical immunity in acute gastroenteritis caused by Norwalk agent. The New England journal of medicine. 1977 Jul 14:297(2):86-9 [PubMed PMID: 405590]

Ford-Siltz LA, Tohma K, Parra GI. Understanding the relationship between norovirus diversity and immunity. Gut microbes. 2021 Jan-Dec:13(1):1-13. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1900994. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33783322]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDe Grazia S, Bonura F, Cappa V, Li Muli S, Pepe A, Urone N, Giammanco GM. Performance evaluation of a newly developed molecular assay for the accurate diagnosis of gastroenteritis associated with norovirus of genogroup II. Archives of virology. 2018 Dec:163(12):3377-3381. doi: 10.1007/s00705-018-4010-8. Epub 2018 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 30191373]

Melgaço FG, Corrêa AA, Ganime AC, Brandão MLL, Medeiros VM, Rosas CO, Lopes SMDR, Miagostovich MP. Evaluation of skimmed milk flocculation method for virus recovery from tomatoes. Brazilian journal of microbiology : [publication of the Brazilian Society for Microbiology]. 2018 Nov:49 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):34-39. doi: 10.1016/j.bjm.2018.04.014. Epub 2018 Aug 16 [PubMed PMID: 30166268]

Hyun J, Ko DH, Lee SK, Kim HS, Kim JS, Song W, Kim HS. Evaluation of a New Multiplex Real-Time PCR Assay for Detecting Gastroenteritis-Causing Viruses in Stool Samples. Annals of laboratory medicine. 2018 May:38(3):220-225. doi: 10.3343/alm.2018.38.3.220. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29401556]

Winder N, Gohar S, Muthana M. Norovirus: An Overview of Virology and Preventative Measures. Viruses. 2022 Dec 16:14(12):. doi: 10.3390/v14122811. Epub 2022 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 36560815]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCohen R, Raymond J, Gendrel D. Antimicrobial treatment of diarrhea/acute gastroenteritis in children. Archives de pediatrie : organe officiel de la Societe francaise de pediatrie. 2017 Dec:24(12S):S26-S29. doi: 10.1016/S0929-693X(17)30515-8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29290231]

Chen Y, Hall AJ, Kirk MD. Norovirus Disease in Older Adults Living in Long-Term Care Facilities: Strategies for Management. Current geriatrics reports. 2017:6(1):26-33. doi: 10.1007/s13670-017-0195-z. Epub 2017 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 29204334]

Fisher A, Dembry LM. Norovirus and Clostridium difficile outbreaks: squelching the wildfire. Current opinion in infectious diseases. 2017 Aug:30(4):440-447. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000382. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28538249]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence