Definition/Introduction

Organizational culture consists of the beliefs and expectations shared by members of an organization.[1] Common norms, values, and perspectives among individuals within a group define its culture.[2] Historically, organizational culture can be viewed as the cultural equivalent of a society’s rituals, symbols, and stories.[3] In modern contexts, the term refers to the collective outlook, assumptions, and standards that shape an organization’s identity.

Several factors influence organizational culture, including structure, leadership, mission, and strategy.[4] A strong organizational culture fosters unity and purpose among employees, helping teams navigate complex and dynamic changes.[5] Clear cultural expectations serve as an asset in achieving goals and enhancing career fulfillment. Analyzing organizational culture can help predict job satisfaction, employee commitment, and the likelihood of success in quality improvement initiatives.

Organizational culture may be analyzed through multiple frameworks. One approach is based on Hofstede’s national cultural dimensions, which define culture using masculinity, power distance, uncertainty avoidance, and pluralism.[6] Hofstede later adapted these dimensions to apply to organizations, introducing categories such as process-oriented versus results-oriented, job-oriented versus employee-oriented, professional versus parochial, open versus closed systems, loose versus tight control, and pragmatic versus normative structures.[7]

Edgar Schein, whose seminal work in the 1990s influenced the study of organizational culture, developed a 3-layer framework. This model includes artifacts, which represent observable elements of the environment; values, which encompass espoused beliefs and norms; and underlying assumptions, which consist of unconscious and taken-for-granted beliefs.[8][9]

Organizational culture may also be described using broader classifications, such as positive or negative and flexible or relationship-based.[10][11] The Competing Values Framework (CVF) has been widely used to assess organizational culture within healthcare and will be explored in more detail in this activity.[12]

Competing Values Framework

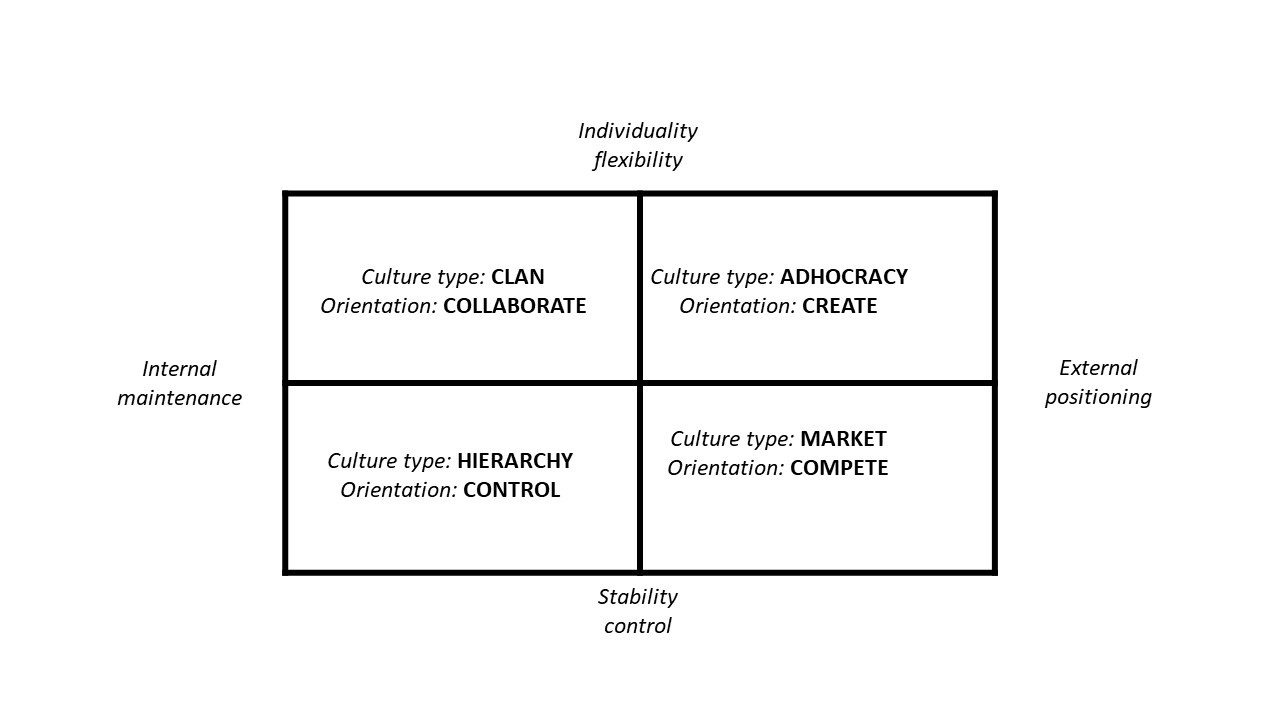

The CVF consists of 2 dimensions that form the foundation of 4 ideal culture types (see Image. Core Dimensions of Competing Values Framework).[13] The horizontal dimension illustrates whether an organization prioritizes internal unity and teamwork or external competitiveness and market differentiation as indicators of effectiveness. The vertical dimension examines whether an organization prioritizes control and consistency or values flexibility and adaptability in achieving effectiveness.[14] Each quadrant represents 1 of the 4 ideal culture types: clan, market, adhocracy, and hierarchy. The CVF model helps determine where an organization’s culture aligns along these dimensions and which ideal culture best describes it.

Clan culture, or group culture, is centered on cooperation, teamwork, and strong interpersonal relationships. Organizations with this culture emphasize employee development, mentoring, and valuing individual input. Similar to a family-like structure, a clan culture fosters cohesion, participation, and shared knowledge, which can support innovation. Managers act as mentors and facilitators, promoting openness, dedication, and growth. (Alsaqqa) Examples are medical directors, residency program directors, chief nursing officers, specialty department heads, healthcare administrators, and nurse managers in teaching hospitals.

While this emphasis on people can enhance long-term engagement and efficiency, this setting may also pose challenges for implementing new developments. Despite this potential hurdle, a focus on human development often leads to lasting organizational benefits.[15]

Market culture is driven by competition and the pursuit of a market advantage. Productivity and profitability take priority, with success measured by goal achievement and external performance.

Market culture in healthcare prioritizes efficiency, performance metrics, and patient outcomes, with success measured by quality benchmarks and financial sustainability. This externally focused culture emphasizes competitiveness, patient satisfaction, and institutional reputation, engaging with insurers, regulators, and other stakeholders to maintain an advantage.

Healthcare organizations with a market culture operate strategically to enhance service delivery, expand patient volume, and improve cost-effectiveness. Leaders function as strategists and performance-driven executives, while employees focus on meeting targets for patient care and operational efficiency. Consistency and control are essential to maintaining effectiveness in this results-oriented environment. A strong emphasis on patient-centered care, data-driven decision-making, and market positioning drives success.[16]

Adhocracy culture fosters creativity through an entrepreneurial and innovative spirit. Agility and transformation define this culture, allowing organizations to adapt quickly in dynamic environments.

Adhocracy culture in healthcare emphasizes innovation, adaptability, and rapid response to emerging challenges. Organizations with this culture prioritize research, technology integration, and novel treatment approaches to improve patient care. Leaders function as visionaries, encouraging creative problem-solving and calculated risk-taking to drive advancements in medical practice and healthcare delivery. Employees are given autonomy to explore new strategies, fostering a proactive and forward-thinking work environment. This externally focused culture thrives in dynamic settings, such as research institutions, biotechnology firms, and hospitals implementing cutting-edge treatments. Success is defined by breakthrough innovations, strategic agility, and long-term growth in an evolving healthcare landscape.[17]

A hierarchical culture emphasizes control through structure, organization, and monitoring. Dependability, repeatability, and standardization are key characteristics ensuring consistency in processes and outcomes.[18]

A hierarchical culture in healthcare prioritizes regulation and standardized protocols to ensure consistency in patient care and safety. Decision-making follows a top-down approach, with policies and procedures guiding clinical and administrative practices. Stability and efficiency are emphasized, making this culture effective in settings such as hospitals and regulatory agencies where adherence to established guidelines is critical. Leaders serve as coordinators and monitors, ensuring compliance with protocols and maintaining operational control. Employees benefit from clear expectations and a structured environment, fostering reliability in care delivery. However, excessive rigidity may limit adaptability, posing challenges in rapidly evolving healthcare scenarios.[19][20]

The CVF provides valuable insight when applied to the organizational culture of a healthcare organization. Every organization exhibits elements of each ideal culture type, but the framework helps assess the extent to which each culture is represented relative to the others. This assessment can inform hypotheses about how organizational culture influences factors such as the success of quality improvement initiatives or the achievement of specific outcomes. For example, a strong emphasis on clan culture often correlates with high physician satisfaction, as physicians tend to value a strong work ethic and contributions to the team. In contrast, a dominant hierarchical culture may lead to lower physician satisfaction, as rigid structures can be perceived as limiting independence and decision-making in patient care.

More descriptive frameworks have been used to categorize organizational culture in research. A systematic review of work-related stress among nurses identified both positive and negative organizational cultures. A positive culture was characterized by authentic leadership, empowerment, teamwork, collaboration, and effective communication, whereas a negative culture lacked these attributes. A positive culture was associated with reduced work-related stress, while a negative culture contributed to increased stress.

Organizational culture may also be defined by its level of flexibility, which is influenced by leadership structure, degree of autonomy, and overall cooperativity. More flexible cultures have been shown to support authentic leadership and facilitate quality improvement efforts. Relationship-based cultures, which emphasize community and human connections, have been associated with lower job stress and reduced turnover intentions among infection control nurses in Korea. In contrast, cultures focused on innovation, tasks, or hierarchy were linked to higher stress levels in this group.

Organizational Culture Assessment Instrument

The Organizational Culture Assessment Instrument (OCAI) is a widely used tool based on the CVF. The OCAI was developed by Kim S. Cameron and Robert E. Quinn at the University of Michigan. This instrument evaluates 6 domains: dominant characteristics, organizational leadership, employee management, organizational glue, strategic emphases, and criteria for success.[21] Each domain includes 4 descriptions, allowing respondents to identify the organizational culture that best represents their workplace.

Responses correspond to the 4 distinct culture types within the framework, providing insight into the organization's current culture. The tool can establish a baseline for strengthening existing cultural attributes or setting future cultural goals. While some studies support the instrument's reliability and validity, others have reported mixed findings.

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

While analyzing organizational culture through the CVF is often insightful and predictive, certain limitations exist. A study by Kava et al found no significant association between organizational culture and the adoption of an antismoking initiative. Surprisingly, a stronger emphasis on clan culture correlated with a lower likelihood of offering smoking cessation activities. Heritage et al reported weak criterion validity when using the OCAI, a variant of the CVF, to assess organizational culture in relation to ideal culture. These findings highlight the need for careful interpretation when applying the framework to predict organizational behavior and outcomes.[22]

Clinical Significance

Organizational culture plays a central role in hospital accreditation, a process that systematically evaluates patient care quality against established medical standards. A study by Andres et al suggested that accreditation can influence staff perceptions of organizational culture, often shifting emphasis away from hierarchical structures toward clan and developmental cultures.

The impact of organizational culture extends beyond hospitals to clinics and office-based practices. Identifying and modifying cultural archetypes can be a strategic part of practice redesign, aligning culture with factors that promote higher provider satisfaction. Certain aspects of physician organizational culture have been linked to improved satisfaction in group practice. Korner et al found that job gratification correlates with both organizational culture and interprofessional teamwork.

Organizational culture also influences staff turnover differently among registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and nurse practitioners. Licensed practical nurses preferred a more flexible culture, while registered nurses favored environments with more structured internal rules.[23]

Organizational culture significantly impacts the work environment. Multiple studies have associated a hierarchical model with negative outcomes. Tate et al found that hierarchical organizational culture correlates with lower quality improvement and patient satisfaction measures.[24] Additionally, hierarchical structures have been linked to decreased retention among primary care providers in China.[25]

In contrast, a study involving French employees found that clan culture fosters a stronger affective commitment to employers, reduces feelings of dehumanization, and enhances perceptions of organizational justice.[26] Affective commitment refers to an employee’s emotional attachment, identification, and involvement in an organization.[27]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Analyzing organizational culture is essential for identifying challenges and implementing strategies to strengthen nursing, allied health, and interprofessional teams. A survey by Poghosyan et al found that nurse practitioners perceived less organizational support and fewer resources than physicians in similar roles. The group also reported inequities in resource allocation and a lack of representation on committees that set organizational policy.[28]

A cohesive and unified organizational culture benefits patient care. In interprofessional healthcare teams conducting ward rounds, a strong group culture fosters collaboration and supports holistic, patient-centered care. However, challenges such as limited time and the complexity of coordinating multiple teams can hinder the implementation of this approach.[29]

Innovation is influenced by organizational culture. In university settings, a hierarchical culture is associated with an environment less conducive to innovation.[30] Hatem H. Alsaqqa, in a commentary on “Innovation in Health Organizations,” emphasized that adaptive health organizations foster a culture of innovation by equipping employees with new skills and knowledge to meet evolving demands and encourage creative solutions. While adhocracy is most strongly linked to innovation, market and clan cultures also support innovative environments.[31] Van den Hoed et al found that organizational cultures promoting innovation are reinforced by dedicated time, training, and prioritization of innovation initiatives.[32]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Examining organizational culture can help assess success within interprofessional teams. Korner et al demonstrated that job satisfaction is linked to both organizational culture and teamwork. Effective team interventions that enhance functionality should be recommended and supported. Accountability among team members, reinforced by patient care partners such as patients and their families, contributes to achieving high-quality patient care. However, optimizing interprofessional teamwork is a continuous process. Incremental changes and gradual improvements strengthen team dynamics and enhance patient safety.[33]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Core Dimensions of the Competing Values Framework. This diagram illustrates the Competing Values Framework, a model that evaluates organizational culture along 2 key dimensions: internal maintenance versus external positioning and control versus flexibility. These dimensions form the foundation for 4 ideal culture types: clan, adhocracy, hierarchy, and market.

Reproduced with permission from Kim Cameron, PhD, University of Michigan; Competing Values Leadership: Second Edition, 2014.

References

Kava CM, Parker EA, Baquero B, Curry SJ, Gilbert PA, Sauder M, Sewell DK. Organizational culture and the adoption of anti-smoking initiatives at small to very small workplaces: An organizational level analysis. Tobacco prevention & cessation. 2018:4():39. doi: 10.18332/tpc/100403. Epub 2018 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 32411865]

Scammon DL, Tabler J, Brunisholz K, Gren LH, Kim J, Tomoaia-Cotisel A, Day J, Farrell TW, Waitzman NJ, Magill MK. Organizational culture associated with provider satisfaction. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine : JABFM. 2014 Mar-Apr:27(2):219-28. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2014.02.120338. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24610184]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZazzali JL, Alexander JA, Shortell SM, Burns LR. Organizational culture and physician satisfaction with dimensions of group practice. Health services research. 2007 Jun:42(3 Pt 1):1150-76 [PubMed PMID: 17489908]

Körner M, Wirtz MA, Bengel J, Göritz AS. Relationship of organizational culture, teamwork and job satisfaction in interprofessional teams. BMC health services research. 2015 Jun 23:15():243. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0888-y. Epub 2015 Jun 23 [PubMed PMID: 26099228]

Andres EB, Song W, Schooling CM, Johnston JM. The influence of hospital accreditation: a longitudinal assessment of organisational culture. BMC health services research. 2019 Jul 9:19(1):467. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4279-7. Epub 2019 Jul 9 [PubMed PMID: 31288810]

Farzianpour F, Abbasi M, Foruoshani AR, Pooyan EJ. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HOFSTEDE ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE AND EMPLOYEES JOB BURNOUT IN HOSPITALS OF TEHRAN UNIVERSITY OF MEDICAL SCIENCES 2014-2015. Materia socio-medica. 2016 Feb:28(1):26-31. doi: 10.5455/msm.2016.28.26-31. Epub 2016 Jan 30 [PubMed PMID: 27047263]

Tabibi SJ, Ebrahimi P, Fardid M, Amiri MS. Designing a model of hospital information system acceptance: Organizational culture approach. Medical journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran. 2018:32():28. doi: 10.14196/mjiri.32.28. Epub 2018 Apr 2 [PubMed PMID: 30159279]

Byrne ZS, Cave KA, Raymer SD. Using a Generalizable Photo-Coding Methodology for Assessing Organizational Culture Artifacts. Journal of business and psychology. 2022:37(4):797-811. doi: 10.1007/s10869-021-09773-0. Epub 2021 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 34690424]

Pedersen MRV, Kusk MW, Lysdahlgaard S, Mork-Knudsen H, Malamateniou C, Jensen J. A Nordic survey on artificial intelligence in the radiography profession - Is the profession ready for a culture change? Radiography (London, England : 1995). 2024 Jul:30(4):1106-1115. doi: 10.1016/j.radi.2024.04.020. Epub 2024 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 38781794]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKiptulon EK, Elmadani M, Limungi GM, Simon K, Tóth L, Horvath E, Szőllősi A, Galgalo DA, Maté O, Siket AU. Transforming nursing work environments: the impact of organizational culture on work-related stress among nurses: a systematic review. BMC health services research. 2024 Dec 2:24(1):1526. doi: 10.1186/s12913-024-12003-x. Epub 2024 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 39623348]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBernardes A, Gabriel CS, Cummings GG, Zanetti ACB, Leoneti AB, Caldana G, Maziero VG. Organizational culture, authentic leadership and quality improvement in Canadian healthcare facilities. Revista brasileira de enfermagem. 2020:73Suppl 5(Suppl 5):e20190732. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2019-0732. Epub 2020 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 33027497]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChoi JS, Kim KM. Effects of nursing organizational culture and job stress on Korean infection control nurses' turnover intention. American journal of infection control. 2020 Nov:48(11):1404-1406. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.04.002. Epub 2020 Apr 11 [PubMed PMID: 32289344]

Helfrich CD, Li YF, Mohr DC, Meterko M, Sales AE. Assessing an organizational culture instrument based on the Competing Values Framework: exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. Implementation science : IS. 2007 Apr 25:2():13 [PubMed PMID: 17459167]

Hartnell CA, Ou AY, Kinicki A. Organizational culture and organizational effectiveness: a meta-analytic investigation of the competing values framework's theoretical suppositions. The Journal of applied psychology. 2011 Jul:96(4):677-94. doi: 10.1037/a0021987. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21244127]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMoreno-Domínguez MJ, Escobar-Rodríguez T, Pelayo-Díaz YM, Tovar-García I. Organizational culture and leadership style in Spanish Hospitals: Effects on knowledge management and efficiency. Heliyon. 2024 Oct 30:10(20):e39216. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e39216. Epub 2024 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 39498020]

Almutairi RL, Aditya RS, Kodriyah L, Yusuf A, Solikhah FK, Al Razeeni DM, Kotijah S. Analysis of organizational culture factors that influence the performance of health care professionals: A literature review. Journal of public health in Africa. 2022 Dec 7:13(Suppl 2):2415. doi: 10.4081/jphia.2022.2415. Epub 2022 Dec 7 [PubMed PMID: 37497141]

D'Silva R, Balakrishnan JM, Bari T, Verma R, Kamath R. Unveiling the Heartbeat of Healing: Exploring Organizational Culture in a Tertiary Hospital's Emergency Medicine Department and Its Influence on Employee Behavior and Well-Being. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2024 Jul 12:21(7):. doi: 10.3390/ijerph21070912. Epub 2024 Jul 12 [PubMed PMID: 39063488]

Sasaki H, Yonemoto N, Mori R, Nishida T, Kusuda S, Nakayama T. Assessing archetypes of organizational culture based on the Competing Values Framework: the experimental use of the framework in Japanese neonatal intensive care units. International journal for quality in health care : journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care. 2017 Jun 1:29(3):384-391. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzx038. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28371865]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFernandopulle N. To what extent does hierarchical leadership affect health care outcomes? Medical journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran. 2021:35():117. doi: 10.47176/mjiri.35.117. Epub 2021 Sep 14 [PubMed PMID: 34956963]

Kim M, Oh S. Assimilating to Hierarchical Culture: A Grounded Theory Study on Communication among Clinical Nurses. PloS one. 2016:11(6):e0156305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156305. Epub 2016 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 27253389]

Van Huy N, Thu NTH, Anh NLT, Au NTH, Phuong NT, Cham NT, Minh PD. The validation of organisational culture assessment instrument in healthcare setting: results from a cross-sectional study in Vietnam. BMC public health. 2020 Mar 12:20(1):316. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-8372-y. Epub 2020 Mar 12 [PubMed PMID: 32164624]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHeritage B, Pollock C, Roberts L. Validation of the organizational culture assessment instrument. PloS one. 2014:9(3):e92879. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092879. Epub 2014 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 24667839]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBanaszak-Holl J, Castle NG, Lin MK, Shrivastwa N, Spreitzer G. The role of organizational culture in retaining nursing workforce. The Gerontologist. 2015 Jun:55(3):462-71. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt129. Epub 2013 Nov 11 [PubMed PMID: 24218146]

Tate K, Penconek T, Dias BM, Cummings GG, Bernardes A. Authentic leadership, organizational culture and the effects of hospital quality management practices on quality of care and patient satisfaction. Journal of advanced nursing. 2023 Aug:79(8):3102-3114. doi: 10.1111/jan.15663. Epub 2023 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 37002558]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLi M, Wang W, Zhang J, Zhao R, Loban K, Yang H, Mitchell R. Organizational culture and turnover intention among primary care providers: a multilevel study in four large cities in China. Global health action. 2024 Dec 31:17(1):2346203. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2024.2346203. Epub 2024 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 38826145]

Hamel JF, Scrima F, Massot L, Montalan B. Organizational Culture, Justice, Dehumanization and Affective Commitment in French Employees: A Serial Mediation Model. Europe's journal of psychology. 2023 Aug:19(3):285-298. doi: 10.5964/ejop.8243. Epub 2023 Aug 31 [PubMed PMID: 37731756]

Allen NJ, Meyer JP. Affective, Continuance, and Normative Commitment to the Organization: An Examination of Construct Validity. Journal of vocational behavior. 1996 Dec:49(3):252-76 [PubMed PMID: 8980084]

Poghosyan L, Norful AA, Martsolf GR. Primary Care Nurse Practitioner Practice Characteristics: Barriers and Opportunities for Interprofessional Teamwork. The Journal of ambulatory care management. 2017 Jan/Mar:40(1):77-86 [PubMed PMID: 27902555]

Walton V, Hogden A, Long JC, Johnson JK, Greenfield D. How Do Interprofessional Healthcare Teams Perceive the Benefits and Challenges of Interdisciplinary Ward Rounds. Journal of multidisciplinary healthcare. 2019:12():1023-1032. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S226330. Epub 2019 Dec 11 [PubMed PMID: 31849478]

Gorzelany J, Gorzelany-Dziadkowiec M, Luty L, Firlej K, Gaisch M, Dudziak O, Scott C. Finding links between organisation's culture and innovation. The impact of organisational culture on university innovativeness. PloS one. 2021:16(10):e0257962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257962. Epub 2021 Oct 8 [PubMed PMID: 34624041]

Alsaqqa HH. Organizational Culture Relation With Innovation Comment on "Employee-Driven Innovation in Health Organizations: Insights From a Scoping Review". International journal of health policy and management. 2024:13():8583. doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.8583. Epub 2024 Sep 7 [PubMed PMID: 39620534]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencevan den Hoed MW, Backhaus R, de Vries E, Hamers JPH, Daniëls R. Factors contributing to innovation readiness in health care organizations: a scoping review. BMC health services research. 2022 Aug 5:22(1):997. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-08185-x. Epub 2022 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 35932012]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceStocker M, Pilgrim SB, Burmester M, Allen ML, Gijselaers WH. Interprofessional team management in pediatric critical care: some challenges and possible solutions. Journal of multidisciplinary healthcare. 2016:9():47-58. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S76773. Epub 2016 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 26955279]