Introduction

Branchial cleft anomalies can develop at any age and are generally benign, though they often resemble other medical conditions. These abnormal structures typically present as neck masses that fluctuate in size, worsening with upper respiratory tract infections and improving during recovery.[1][2] Most cases involve 2nd branchial cleft cysts, which appear as nontender, fluctuant masses along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM), sometimes posing a diagnostic challenge for clinicians and pathologists.[3] These cysts result from the incomplete obliteration of branchial sinuses during embryonic development. While many remain asymptomatic, some become infected or form abscesses, leading to enlargement, pain, and drainage.

Diagnosis relies on clinical suspicion, as no specific tests or imaging studies are universally recommended.[4] Definitive treatment involves elective surgical excision, though urgent intervention may be required in cases of airway compromise.[5][6] In some instances, an endoscope-assisted approach may be preferred.[7][8] With appropriate management, most patients recover without complications. Rarely, branchiogenic carcinoma has been reported within branchial cleft cysts, though it remains unclear whether these cases represent true malignancies or cystic lymph node metastases.[9]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Understanding the causes and pathology of branchial cleft anomalies requires knowledge of fetal development. The branchial, or pharyngeal, structures arise from mesodermal arches containing neural crest cells, with 6 pairs of branchial arches forming early in development. These cells migrate into the developing head and neck during the 4th week of gestation. The pharyngeal apparatus consists of arches, grooves (clefts), and pouches, each composed of mesoderm, lined externally by ectoderm and internally by endoderm.[10]

Typically, 5 branchial arches develop, separated by ectodermal clefts and corresponding endodermal pouches, resulting in 4 pharyngeal clefts.[11] The 2nd arch grows caudally, eventually covering the 3rd and 4th arches.[12] The buried clefts form ectoderm-lined cavities that usually resolve by the 7th week of gestation. Failure of complete involution can result in cysts, sinuses, or fistulae, with their location determined by the branchial cleft of origin.[13]

Embryological Derivatives of the Branchial Apparatus

Each branchial arch contributes distinct structures to the developing head and neck, including cartilage, muscles, nerves, and blood vessels. Understanding these derivatives helps explain the anatomical locations and clinical presentations of branchial cleft anomalies.

Second branchial cleft

Derivatives of the 2nd branchial cleft (hyoid arch) include the following structures:

- Cartilage: Reichert cartilage

- Bones: Stapes, styloid process, lesser horn and upper half of the hyoid bone

- Nerve: Facial nerve (cranial nerve VII)

- Muscles: Muscles of facial expression, stapedius, stylohyoid, posterior belly of digastric

- Arteries: Stapedial artery (usually obliterates)

- Other structures: Lining (crypts) of palatine tonsils

- Cleft: Obliterates

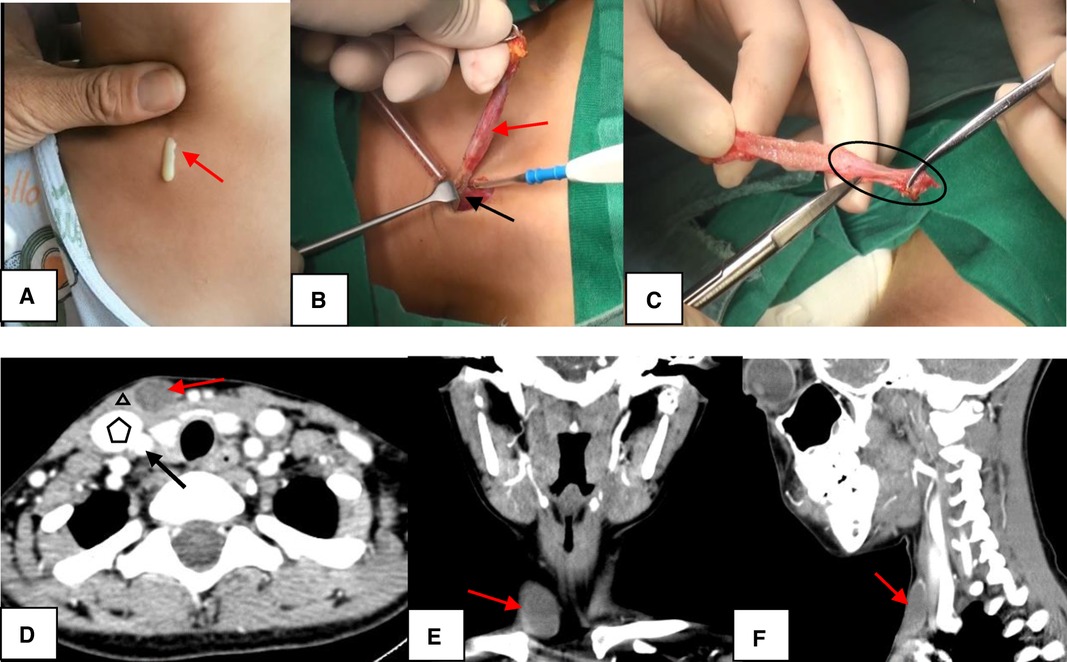

Second branchial cleft cysts are the most common, accounting for 40% to 95% of all branchial cleft anomalies (see Image. Second Branchial Cleft Anomaly). These cysts form when elements of the cervical sinus of His become trapped, leading to an epithelium-lined cyst without an external or internal opening. Another theory suggests that remnants of tissue associated with the Waldeyer ring contribute to their development. Pure branchial cleft cysts or sinuses are rare, as they often present in combination.[14][15]

First branchial cleft

Derivatives of the 1st branchial cleft include the following:

- Cartilage: Meckel cartilage

- Bones: Malleus, incus, portion of the mandible

- Nerve: Trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V)

- Muscles: Muscles of mastication, tensor tympani, tensor palatini, mylohyoid, anterior belly of digastric

- Arteries: Maxillary artery

- Pouch: Eustachian tube, middle ear

- Cleft: External auditory canal (EAC)

The 1st branchial cleft (mandibular arch) is involved in 5% to 25% of all branchial cleft anomalies, making it the 2nd most commonly affected cleft.

Third branchial cleft

Derivatives of the 3rd branchial cleft include the following:

- Bone: Greater horn and lower half of the hyoid bone

- Nerve: Glossopharyngeal nerve (cranial nerve IX)

- Muscle: Stylopharyngeus

- Arteries: Common and internal carotid arteries

- Other structures: Inferior parathyroid gland, thymus

- Cleft: Obliterates

Anomalies of the 3rd branchial cleft are less common, accounting for 2% to 8% of cases.

4th branchial cleft

Derivatives of the 4th branchial cleft include the following:

- Cartilage: Thyroid cartilage, epiglottic cartilage

- Nerve: Vagus nerve (cranial nerve X), superior laryngeal nerve

- Muscles: Cricothyroid, all muscles of the pharynx (except stylopharyngeus), all muscles of the soft palate (except tensor palatini)

- Arteries: Aortic arch, subclavian artery

- Other structures: Superior parathyroid gland, C-cells of the thyroid

- Cleft: Obliterates

Cysts of the 4th branchial cleft are extremely rare, occurring in fewer than 1% of cases.

5th branchial arch

The 5th arch is transient. This embryonic segment does not give rise to any structures.

6th branchial cleft

Derivatives of the 6th branchial cleft include the following:

- Cartilage: Cricoid cartilage, arytenoid complex

- Nerve: Vagus nerve (cranial nerve X), recurrent laryngeal nerve

- Muscles: Intrinsic muscles of the larynx (except cricothyroid)

- Arteries: Pulmonary arteries, ductus arteriosus

- Cleft: Obliterates

Anomalies of the 6th branchial cleft are rare.[16]

Epidemiology

Branchial cleft cysts are the most common cause of congenital neck masses, comprising about 1/3 of cases. The exact incidence of these cysts in the U.S. population remains unknown. Most otolaryngologists encounter at least 1 patient with bilateral branchial clefts in their career, as bilateral cysts occur in 10% of cases. While a family history increases the condition's likelihood, no predilection for gender or race has been reported. Although typically diagnosed in childhood, branchial cleft anomalies have also been identified in adults.[17] Most arise from the 2nd pouch and are usually present in children younger than 10. However, the diagnosis may be delayed until early adulthood if no fistula or drainage is present.

Pathophysiology

Branchial cleft cysts are developmental anomalies resulting from incomplete obliteration during embryogenesis. These abnormal structures can present as cysts, fistulae, sinus tracts, or remnants of cartilage. Clinically, these cysts are typically found in the anterior neck and upper chest.

A branchial cleft cyst has no opening to the skin or digestive tract. A sinus has a single opening. A fistula has openings to both. In about 90% of cases, branchial cleft cysts are lined with stratified squamous epithelium.

Patients with preauricular pits or multiple branchial cleft anomalies, including bilateral cases, should be evaluated for branchiootorenal (BOR) and branchiooculofacial (BOF) syndromes. BOR syndrome, an autosomal dominant condition, is associated with hearing loss, ear malformations, and renal anomalies. BOF syndrome includes eye anomalies such as microphthalmia and obstructed lacrimal ducts, along with facial anomalies like cleft lip and palate.

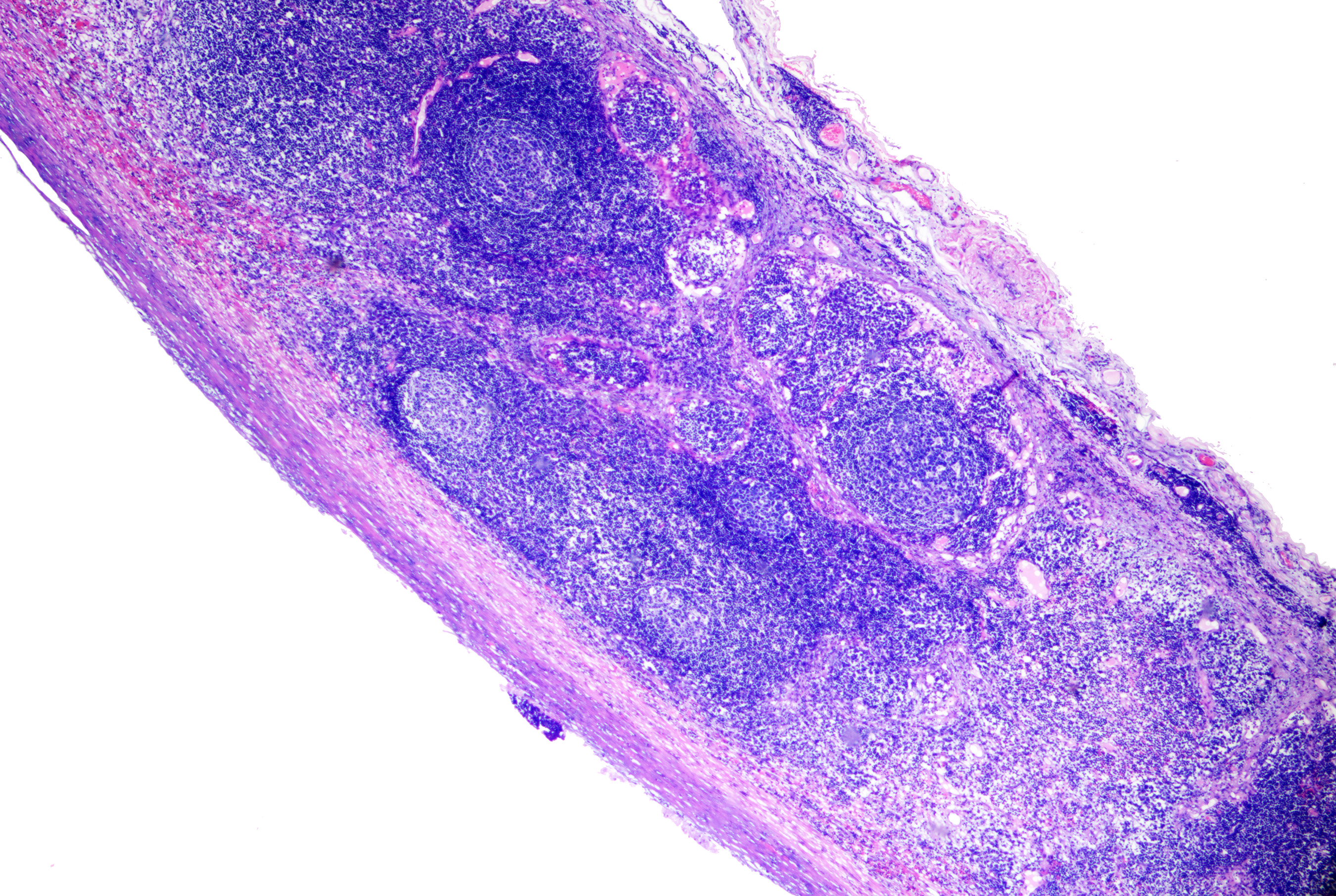

Histopathology

Branchial cleft cysts are characterized by an epithelial lining composed of stratified squamous epithelium, which may contain keratinous debris within the cyst. In certain instances, the cyst wall may be lined by ciliated columnar epithelium, resulting in a more mucoid consistency of the contents. Lymphoid tissue typically surrounds the epithelial lining. Infection or rupture can introduce inflammatory cells into the cavity or stroma (see Image. Branchial Cyst on Histopathology).

History and Physical

A branchial cleft cyst typically presents as a nontender, fluctuant mass located on the lateral neck beneath the SCM. These cysts can become inflamed and tender, especially in the presence of upper respiratory tract infections, and may cause enlargement by 25% or more. In such cases, patients may observe purulent drainage from the sinus, appearing as discharge from the skin or pharynx. Severe symptoms, including dysphagia, dyspnea, and stridor, can arise if the cyst compresses the upper airway.[18]

Branchial cleft cysts vary in presentation depending on their location. First branchial cleft cysts are usually smooth, nontender, and fluctuant. An otologic exam is crucial for diagnosis.[19] These cysts are classified into 2 subtypes. Work type I presents as a preauricular cyst with a duplicated EAC composed entirely of ectodermal elements. The tract follows a path lateral to cranial nerve VII, parallels the EAC, and terminates in the mesotympanum.

In contrast, Work type II is more common and typically appears near the mandibular angle, periauricular area, or submandibular region. These cysts contain both ectodermal and mesodermal components. Around 57% of type II cysts pass lateral to cranial nerve VII, while 30% pass medially, often terminating within or near the EAC. Surgical management of 1st arch anomalies requires careful identification of the facial nerve. In some cases, a superficial or total parotidectomy may be necessary.

Second branchial cleft cysts typically present as a pit or punctum along the lower anterior border of the SCM. When an associated sinus is present, the tract may terminate internally in the tonsillar fossa. These cysts are located near the glossopharyngeal and hypoglossal nerves, as well as the carotid vessels. They can become tender if secondarily infected and, in rare cases, may cause airway compromise. A mucoid or purulent discharge may be observed if a sinus tract is involved.[20]

Third and 4th branchial cleft cysts are rare and typically occur on the left side of the neck, the suprasternal notch, or the clavicular region. These anomalies present as firm masses or infected cysts that drain into the piriform sinus or externally. The cysts are more likely to be recognized when infected. The elusive diagnosis of these lesions often results in repeated incision and drainage procedures, increasing the risk of recurrence.[21]

Evaluation

No specific laboratory tests are required for evaluation. However, additional assessments may be necessary when malignancy is suspected or the diagnosis remains unclear.

Fine needle aspiration cytology may be less reliable than frozen sections following surgical excision of cystic masses. The false negative rate for fine needle aspiration cytology in diagnosing squamous cell carcinoma from cystic metastases exceeds 50%, mainly due to insufficient diagnostic cellular material.[22][23]

Imaging studies vary in effectiveness and utility, with different modalities offering distinct advantages depending on the clinical scenario.[24] A computed tomography (CT) scan with intravenous contrast is particularly useful when the clinical history is unclear or an abscess is suspected. While sinus tracts are typically visible only during inflammation, their relationship to cervical vasculature can help identify the affected arch. CT imaging also guides surgical planning and is relatively low-cost. CT risks significant radiation exposure to young children. However, if imaging is warranted and other studies are not feasible, sedation may be required for pediatric patients undergoing CT.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides superior soft tissue detail, demonstrating cystic lesions with low-to-intermediate T1-weighted and high T2-weighted signal intensity. Chronically infected cysts may exhibit a high T1-weighted signal. Gadolinium contrast is preferred to visualize any tract and assess its relationship to the facial nerve and the parotid gland. Like CT, MRI may also require sedation for young children.

Ultrasound offers a noninvasive, cost-effective option for evaluating cyst characteristics and assisting in surgical planning. However, this modality is highly operator-dependent. A barium esophagram can help identify an opening in the hypopharynx that tracks to the neck, but it is most effective when combined with a noncontrast-enhanced CT. Despite its utility, a barium esophagram should never replace direct laryngoscopy and direct visualization.

A CT sinogram involves injecting radiopaque dye into a sinus tract to delineate its course. Research has explored sinogram data in image reconstruction and deep learning applications.[25]

Overall, CT remains the superior imaging modality, confirming ultrasound findings, defining lesion extent, and effectively demonstrating calcification or fat within the lesion. MRI serves as a supplementary tool in the evaluation of cystic neck masses.[26]

Treatment / Management

A definitive diagnosis of a branchial cleft cyst is obtained through surgical excision and pathological evaluation. Surgery is generally recommended only after the patient reaches at least 3 months of age or once any acute infection has been treated. Incision and drainage should be avoided, as it may lead to recurrence.[27] In rare cases, emergent surgery is necessary when airway compromise or a large abscess is present.(B2)

Complete excision of the cyst, tract, and sinus is preferred to minimize recurrence. This procedure may require the use of a probe or catheter, methylene blue injection with a probe, or stepladder incisions to ensure all components are removed. First branchial cleft cysts may necessitate facial nerve dissection with superficial parotidectomy, while 3rd and 4th branchial cleft cysts may require recurrent laryngeal nerve identification or thyroid lobectomy. Direct laryngoscopy is often performed to cannulate the opening into the pyriform sinus. Some consider cauterization of the pyriform sinus tract sufficient for treating 3rd and 4th branchial cleft cysts.

To reduce significant scarring, alternative approaches to open surgery have been explored, though their results and drawbacks vary. The endoscopic retroauricular approach has been proposed for 2nd branchial cleft cysts.[28][29][30] Sclerotherapy using OK-432 (picibanil), sometimes performed under ultrasonographic guidance, has been employed as a minimally invasive option.[31][32] Other sclerotherapy methods involve agents such as ethanol, doxycycline, tetracycline, and bleomycin.[33](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of branchial cleft anomalies includes the following:

- Lymphadenopathy (ie, reactive, neoplastic, lymphomatous, or metastatic)

- Paramedian thyroglossal duct cyst

- Infectious adenitis (eg, from tuberculosis or cat scratch disease)

- Vascular neoplasms and malformations

- Lymphatic malformations

- Neurogenic tumors with cystic degeneration (eg, schwannoma)

- Cervical dermoid cysts

- Capillary hemangioma

- Carotid body tumor

- Cystic hygroma

- Ectopic thyroid

- Ectopic salivary gland

- Hydatid cyst [34]

Accurate differentiation between branchial cleft anomalies and other cervical masses is critical for appropriate treatment. Surgical excision is the preferred approach, but emerging minimally invasive techniques may be considered in select cases.

Prognosis

Untreated branchial cleft cysts are susceptible to recurrent infections and abscess formation. Complete surgical excision is the preferred treatment, as these cysts are typically benign and require no further intervention once removed. Clinicians should monitor for recurrence and consider the possibility of bilateral presentations in some patients. The estimated recurrence rate is approximately 3%, but it can rise to 20% in individuals who had prior surgery or recurrent infections. Malignancy is rare.

Complications

Complications of branchial cleft anomalies vary depending on their location and characteristics. Acute infections and abscess formation are common concerns. Administering appropriate antibiotics before definitive surgical excision can help mitigate these risks. A thorough understanding of embryology, pathophysiology, and anatomy is essential to avoid damage to nearby vascular and neural structures, including the facial, hypoglossal, vagus, recurrent laryngeal, and lingual nerves.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Most patients are discharged within 24 hours of surgery and need minimal or no postoperative pain management. Postoperative care is typically straightforward, as most surgeons opt for subcutaneous wound closure using absorbable sutures and minimal neck dressing. Some patients may require a temporary neck drain. Patients should limit activity for 7 to 10 days to promote proper wound healing.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Most patients with a branchial cleft anomaly are referred for evaluation due to a solitary, painless mass that may fluctuate in size or become acutely inflamed in children or young adults. Swelling, redness, and tenderness frequently recur, particularly following acute upper respiratory infections. A neck mass with purulent or serous discharge often raises suspicion of an embryologic origin. In rare cases, patients may experience compressive symptoms such as dysphagia or airway obstruction. A thorough assessment should include an investigation of any family history of branchial cleft anomalies. While no preventive measures exist, early diagnosis and appropriate treatment can improve outcomes and reduce complications.

Genetic counseling should be considered for patients with bilateral branchial cleft anomalies, a family history of similar lesions, or additional congenital features suggestive of syndromic associations, such as BOR or BOF syndrome. Early referral is recommended when preauricular pits, hearing loss, renal anomalies, or craniofacial malformations are present to evaluate potential genetic causes and inheritance patterns.

Pearls and Other Issues

Branchial cleft cysts are the most common congenital neck masses, typically presenting as nontender, fluctuant swellings along the anterior border of the SCM. These anomalies often become more noticeable during or after an upper respiratory tract infection. Of the 4 types described, 2nd branchial cleft cysts are the most prevalent. Healthcare professionals should consider branchial cleft cysts in the differential diagnosis of a neck mass in both children and adults. The preferred treatment is surgical excision, performed once any acute infection has been adequately treated.

Other important points to remember regarding the evaluation and management of branchial cleft anomalies include the following:

- A comprehensive knowledge of branchial arch derivatives is critical for effective surgical management.

- Incision and drainage should be avoided.

- Acute infection and abscess should be treated prior to definitive surgical excision.

- Delaying surgery until 3 months of age is preferred.

- Second branchial arch anomalies are most common, and evaluation for a sinus tract should be undertaken to avoid recurrence.

- First branchial arch anomalies may present with a history of preauricular infections and otorrhea despite a normal tympanic membrane.

- Identification and intraoperative monitoring of cranial nerves should be anticipated during surgical excision.

- Imaging should be undertaken for surgical guidance.

- Direct laryngoscopy should be used to identify 3rd and 4th branchial cleft fistulae.

- In adults, cystic metastasis should be considered as a differential diagnosis.

- Alternatives to surgical excision may increase scarring and decrease patient outcomes and satisfaction.

Genetic counseling should be considered for cases with bilateral anomalies, a family history, or syndromic features such as BOR or BOF syndrome, particularly when hearing loss or craniofacial abnormalities are present.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of branchial cleft anomalies requires a coordinated, interprofessional healthcare team committed to patient-centered care, improved outcomes, safety, and optimal team performance. This collaborative effort involves otolaryngologists, family physicians, pediatricians, pathologists, radiologists, nurses, pharmacists, and hospital staff. Although complete surgical excision is the preferred treatment, medical management may be necessary in cases of infection or abscess formation.

Otolaryngologists must have a comprehensive understanding of head and neck embryology, pathophysiology, and anatomy. Preoperative and postoperative care should include educating patients about branchial cleft cysts, the potential presence of sinus tracts or fistulae, and the importance of complete excision to prevent recurrence.

Clear and effective communication among healthcare team members is essential. Physicians and nurses must promptly identify signs of a branchial cleft cyst and advise against incision and drainage or partial removal, as these interventions can lead to scarring, recurrence, and complications such as nerve or vascular injury. Open communication supports timely diagnosis and treatment decisions, reducing errors and enhancing patient safety.

Informed consent is particularly important, as most patients with branchial cleft anomalies are very young. Ongoing education and training ensure that healthcare providers remain up to date on best practices tailored to individual patient needs. Continuous professional development equips the team to manage branchial cleft anomalies effectively.

A patient-centered approach remains the foundation of care, prioritizing patient well-being and preferences in all decisions. An interprofessional healthcare team ensures a comprehensive strategy that minimizes complications, enhances patient safety, improves care quality, and reduces the risk of recurrence.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Second Branchial Cleft Anomaly. In Image A, the sinus appears as a skin pit on the lateral neck with discharge from the skin opening (red arrow). In Image B, the sinus (red arrow) terminates at the surface of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle (black arrow). In Image C, the end of the sinus closes, forming a muscle bundle (circle) that ends at the surface of the SCM. In Images D to F, computed tomography scans show the lesion (red arrow) lying along the anterior surface of the SCM (triangle), just deep to the platysma and not in contact with the carotid sheath (pentagon: internal jugular vein; black arrow: common carotid artery). Image D represents the axial view, Image E the coronal view, and Image F the sagittal view.

Chen W, Zhou YU, Xu M, et al. Congenital second branchial cleft anomalies in children: a report of 52 surgical cases, with emphasis on characteristic CT findings. Front Pediatr. 2023;11:1088234.

doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.1088234.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Koch EM, Fazel A, Hoffmann M. Cystic masses of the lateral neck - Proposition of an algorithm for increased treatment efficiency. Journal of cranio-maxillo-facial surgery : official publication of the European Association for Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surgery. 2018 Sep:46(9):1664-1668. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2018.06.004. Epub 2018 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 29983308]

Coste AH, Lofgren DH, Shermetaro C. Branchial Cleft Cyst. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763089]

Fanous A, Morcrette G, Fabre M, Couloigner V, Galmiche-Rolland L. Diagnostic Approach to Congenital Cystic Masses of the Neck from a Clinical and Pathological Perspective. Dermatopathology (Basel, Switzerland). 2021 Aug 1:8(3):342-358. doi: 10.3390/dermatopathology8030039. Epub 2021 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 34449578]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBansal AG, Oudsema R, Masseaux JA, Rosenberg HK. US of Pediatric Superficial Masses of the Head and Neck. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2018 Jul-Aug:38(4):1239-1263. doi: 10.1148/rg.2018170165. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29995618]

Prada LR, Koripalli VS, Merino CL, Fulger I. A Case of a Rapidly Enlarging Neck Mass with Airway Compromise. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2017 May:11(5):OD14-OD16. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/25685.9874. Epub 2017 May 1 [PubMed PMID: 28658834]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchmidt K, Leal A, McGill T, Jacob R. Rapidly enlarging neck mass in a neonate causing airway compromise. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center). 2016 Apr:29(2):183-4 [PubMed PMID: 27034563]

Teng SE, Paul BC, Brumm JD, Fritz M, Fang Y, Myssiorek D. Endoscope-assisted approach to excision of branchial cleft cysts. The Laryngoscope. 2016 Jun:126(6):1339-42. doi: 10.1002/lary.25711. Epub 2015 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 26466762]

Bee-See G, Anuar NA. Endoscopic diagnostic and therapeutic management of branchial cleft fistula type III & IV: a single tertiary centre experience. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2024 Dec:281(12):6711-6715. doi: 10.1007/s00405-024-08853-0. Epub 2024 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 39073435]

Singh B, Balwally AN, Sundaram K, Har-El G, Krgin B. Branchial cleft cyst carcinoma: myth or reality? The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 1998 Jun:107(6):519-24 [PubMed PMID: 9635463]

Ryu J, Igawa T, Mohole J, Coward M. Congenital Neck Masses. NeoReviews. 2023 Oct 1:24(10):e642-e649. doi: 10.1542/neo.24-10-e642. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37777610]

Tazegul G, Bozoğlan H, Doğan Ö, Sari R, Altunbaş HA, Balci MK. Cystic lateral neck mass: Thyroid carcinoma metastasis to branchial cleft cyst. Journal of cancer research and therapeutics. 2018 Oct-Dec:14(6):1437-1438. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.188440. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30488872]

Oh JH, Chang YW, Lee EJ. Sonographic diagnosis of coexisting ectopic thyroid and fourth branchial cleft cyst. Journal of clinical ultrasound : JCU. 2018 Nov:46(9):582-584. doi: 10.1002/jcu.22630. Epub 2018 Oct 4 [PubMed PMID: 30288756]

Williams DS. Neck Mass in a Five-year-old Afghan Child. Journal of insurance medicine (New York, N.Y.). 2018 Jan:47(3):191-193. doi: 10.17849/insm-47-03-191-193.1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30192721]

Lee DH, Yoon TM, Lee JK, Lim SC. Clinical Study of Second Branchial Cleft Anomalies. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2018 Sep:29(6):e557-e560. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000004540. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29608472]

Allen SB, Jamal Z, Goldman J. Branchial Cleft Cysts. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29494074]

Prosser JD, Myer CM 3rd. Branchial cleft anomalies and thymic cysts. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2015 Feb:48(1):1-14 [PubMed PMID: 25442127]

Teo NW, Ibrahim SI, Tan KK. Distribution of branchial anomalies in a paediatric Asian population. Singapore medical journal. 2015 Apr:56(4):203-7 [PubMed PMID: 25917471]

Possel L, François M, Van den Abbeele T, Narcy P. [Mode of presentation of fistula of the first branchial cleft]. Archives de pediatrie : organe officiel de la Societe francaise de pediatrie. 1997 Nov:4(11):1087-92 [PubMed PMID: 9488742]

Xiao H, Kong W, Gong S, Wang J, Liu S, Shi H. [Surgical treatment of first branchial cleft anomaly]. Lin chuang er bi yan hou ke za zhi = Journal of clinical otorhinolaryngology. 2005 Oct:19(19):873-4 [PubMed PMID: 16419954]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShen LF, Zhou SH, Chen QQ, Yu Q. Second branchial cleft anomalies in children: a literature review. Pediatric surgery international. 2018 Dec:34(12):1251-1256. doi: 10.1007/s00383-018-4348-8. Epub 2018 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 30251021]

Quintanilla-Dieck L, Penn EB Jr. Congenital Neck Masses. Clinics in perinatology. 2018 Dec:45(4):769-785. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2018.07.012. Epub 2018 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 30396417]

Stefanicka P, Profant M. Branchial cleft cyst and branchial cleft cyst carcinoma, or cystic lymph node and cystic nodal metastasis? The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2023 Jan:137(1):31-36. doi: 10.1017/S0022215122001293. Epub 2022 Jun 17 [PubMed PMID: 35712979]

Layfield LJ, Esebua M, Schmidt RL. Cytologic separation of branchial cleft cyst from metastatic cystic squamous cell carcinoma: A multivariate analysis of nineteen cytomorphologic features. Diagnostic cytopathology. 2016 Jul:44(7):561-7. doi: 10.1002/dc.23461. Epub 2016 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 26956661]

Friedman E, Patiño MO, Udayasankar UK. Imaging of Pediatric Salivary Glands. Neuroimaging clinics of North America. 2018 May:28(2):209-226. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2018.01.005. Epub 2018 Mar 7 [PubMed PMID: 29622115]

Li Y, Li K, Zhang C, Montoya J, Chen GH. Learning to Reconstruct Computed Tomography Images Directly From Sinogram Data Under A Variety of Data Acquisition Conditions. IEEE transactions on medical imaging. 2019 Oct:38(10):2469-2481. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2019.2910760. Epub 2019 Apr 11 [PubMed PMID: 30990179]

Mittal MK, Malik A, Sureka B, Thukral BB. Cystic masses of neck: A pictorial review. The Indian journal of radiology & imaging. 2012 Oct:22(4):334-43. doi: 10.4103/0971-3026.111488. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23833426]

Mattioni J, Azari S, Hoover T, Weaver D, Chennupati SK. A cross-sectional evaluation of outcomes of pediatric branchial cleft cyst excision. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2019 Apr:119():171-176. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.01.030. Epub 2019 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 30735909]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChen LS, Sun W, Wu PN, Zhang SY, Xu MM, Luo XN, Zhan JD, Huang X. Endoscope-assisted versus conventional second branchial cleft cyst resection. Surgical endoscopy. 2012 May:26(5):1397-402. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-2046-x. Epub 2011 Dec 17 [PubMed PMID: 22179440]

Chen L, Huang X, Lou X, Xhang S, Song X, Lu Z, Xu M. [A comparison between endoscopic-assisted second branchial cleft cyst resection via retroauricular hairline approach and conventional second branchial cleft cyst resection]. Lin chuang er bi yan hou tou jing wai ke za zhi = Journal of clinical otorhinolaryngology head and neck surgery. 2013 Nov:27(22):1258-62 [PubMed PMID: 24616985]

Meijers S, Meijers R, van der Veen E, van den Aardweg M, Bruijnzeel H. A Systematic Literature Review to Compare Clinical Outcomes of Different Surgical Techniques for Second Branchial Cyst Removal. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2022 Apr:131(4):435-444. doi: 10.1177/00034894211024049. Epub 2021 Jun 17 [PubMed PMID: 34137276]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKim MG, Kim SG, Lee JH, Eun YG, Yeo SG. The therapeutic effect of OK-432 (picibanil) sclerotherapy for benign neck cysts. The Laryngoscope. 2008 Dec:118(12):2177-81. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e3181864acf. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19029851]

Kim JH. Ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy for benign non-thyroid cystic mass in the neck. Ultrasonography (Seoul, Korea). 2014 Apr:33(2):83-90. doi: 10.14366/usg.13026. Epub 2014 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 24936500]

Talmor G, Nguyen B, Mir G, Badash I, Kaye R, Caloway C. Sclerotherapy for Benign Cystic Lesions of the Head and Neck: Systematic Review of 474 Cases. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2021 Dec:165(6):775-783. doi: 10.1177/01945998211000448. Epub 2021 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 33755513]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceIranpour P, Masroori A. Hydatid cyst of the neck mimicking a branchial cleft cyst. BMJ case reports. 2018 Aug 9:2018():. pii: bcr-2018-225065. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-225065. Epub 2018 Aug 9 [PubMed PMID: 30093467]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence