Introduction

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP) is a disease of disordered keratinization. This condition represents 1 of 6 porokeratosis variants and involves more extensive distribution than most others. Linear porokeratosis, porokeratosis of Mibelli, punctate porokeratosis, porokeratosis palmaris et plantaris disseminata, and disseminated superficial porokeratosis comprise the remaining 5 variants. Other rare forms include porokeratosis ptychotropica, facial porokeratosis, giant porokeratosis, hypertrophic verrucous porokeratosis, reticulate porokeratosis, and eruptive pruritic papular porokeratosis. The eruptive form has been linked to malignancy, immunosuppression, and a pro-inflammatory state. Lesions develop across the body. Risk factors for porokeratosis include genetic predisposition, immunosuppression, and ultraviolet light exposure.

A defining feature of all porokeratosis variants is the cornoid lamella, which appears histologically as a column of parakeratotic cells. This structure is characterized by a raised ridge circumscribing porokeratotic lesions. DSAP lesions begin as pink to brown papules and macules with a raised border in sun-exposed areas. These lesions may be asymptomatic or mildly pruritic. DSAP is considered precancerous, with a 7.5% to 10% risk of malignant transformation to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Multiple treatment options exist, including topical diclofenac, photodynamic therapy (PDT), 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), imiquimod, vitamin D analogs (eg, calcipotriene), retinoids, and lasers.[1][2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Genetics, ultraviolet radiation, trauma, infection, and immunosuppression (including posttransplant immune dysfunction) contribute to porokeratosis. Cases have been reported in recipients of kidney transplants, children with acute leukemia, and individuals receiving multiple medications, such as hydroxyurea or other immunosuppressive agents.[3][4][5][6][7] A familial form of DSAP follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern with incomplete penetrance. Mutations in the mevalonate kinase (MVK) gene on chromosome 12q24 have been identified in individuals with DSAP. MVK encodes mevalonate kinase, an enzyme involved in cholesterol synthesis that plays a role in protecting cells from ultraviolet light-induced damage.[8]

DSAP has the highest incidence among porokeratosis variants. The potential for malignant transformation arises from p53 overexpression, particularly in chronic or large lesions and those affecting older adults or immunocompromised individuals.[9][10]

Epidemiology

DSAP is the most common porokeratosis variant, accounting for 56% of cases. Although DSAP shows a slight female predominance, porokeratosis as a whole is more common in male individuals. Onset typically occurs in the 30s and 40s.

Histopathology

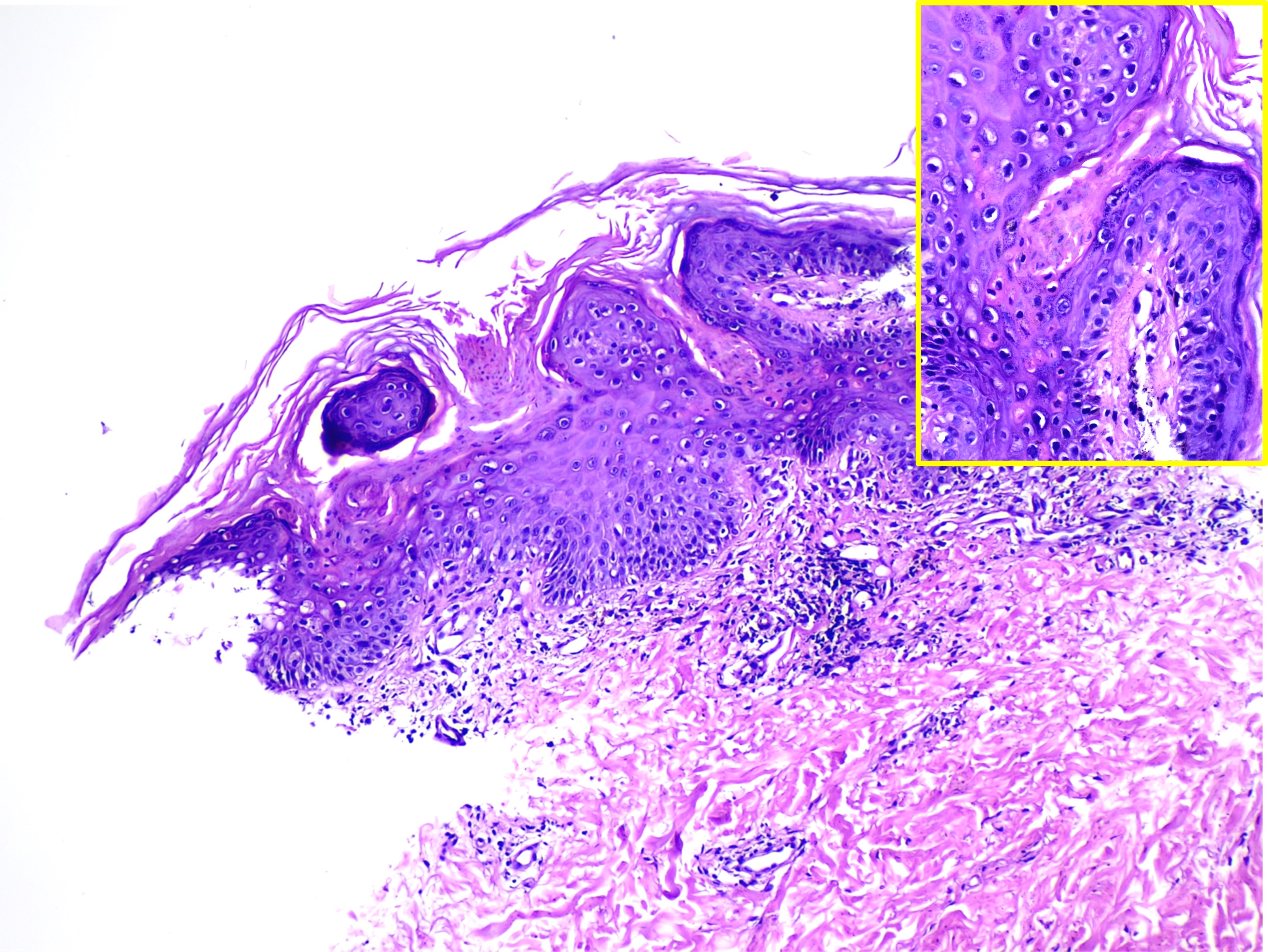

A skin biopsy should include the lesion’s border, where a column of parakeratotic cells corresponding to the raised edge is observed. This column, known as the cornoid lamella, overlies a granular layer that may be thinned or absent. Dyskeratosis occurs in the underlying epidermis, and spongiosis may be present (see Image. Cornoid Lamellae on Histopathology).

History and Physical

Lesions present as asymptomatic or pruritic annular erythematous or brown macules, papules, or plaques with a raised hyperkeratotic border. Bilateral involvement can occur. DSAP most commonly appears in the 3rd or 4th decade and affects sun-exposed areas, with the legs, forearms, shoulders, and back being the most frequently involved sites (see Image. Disseminated Superficial Actinic Porokeratosis). Facial involvement is rare, and the palms and soles remain unaffected. Sun exposure often exacerbates DSAP, with pruritus potentially intensifying.[11] Dermoscopy may reveal a double margination of the peripheral white border.[12] Unlike actinic keratosis, DSAP lesions exhibit scaling along the periphery rather than centrally. Individuals with DSAP or lesions suspicious for DSAP should undergo a full-body skin examination to assess for additional lesions or skin cancer.

Evaluation

The characteristic appearance of DSAP allows for a clinical diagnosis. Dermoscopy and physical examination may be used for monitoring, reducing the need for a skin biopsy. However, when uncertainty exists, a biopsy may be performed. Nicola et al identified key dermoscopic features of porokeratotic lesions, including a white border encircling the lesion, a homogeneous central white scar-like area, brownish globules or dots, and vascular structures, such as pinpoint or irregular linear vessels crossing the lesion.[13]

Treatment / Management

Treatment options for DSAP aim to reduce lesion burden, alleviate symptoms, and prevent malignant transformation. While no single therapy is universally effective, various topical, procedural, and systemic interventions have shown efficacy in managing the condition.

Topical Diclofenac

Diclofenac, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) that inhibits cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), is approved for actinic keratosis and has been used in DSAP with variable success. This medication has a favorable safety profile and has been effective in stabilizing lesions, including those in genital areas, while also providing symptomatic relief.[14](B3)

Topical Vitamin D Analog

Vitamin D3 analogs have demonstrated favorable responses after 6 to 8 weeks of use. These drugs induce the transcription of genes that regulate keratinocyte differentiation and proliferation.

5-Fluorouracil

5-FU inhibits thymidylate synthase, disrupting DNA synthesis and targeting rapidly proliferating cells. The use of this agent often triggers a pronounced inflammatory reaction, which may include erythema, ulceration, and dermatitis. Clinical improvements are typically temporary.

Imiquimod

Imiquimod stimulates the immune response by activating toll-like receptors 7 and 8, leading to cytokine induction and immune cell recruitment. This drug has primarily been used for porokeratosis of Mibelli and porokeratosis palmaris et plantaris. Treatment can trigger an inflammatory response similar to that seen with 5-FU.

Photodynamic Therapy

PDT has been employed in the management of actinic keratosis, BCC, and SCC in situ. This treatment modality involves the application of a photosensitizer, which is selectively taken up by atypical keratinocytes. The most commonly used PDT photosensitizers are 5-aminolevulinic acid and methyl aminolevulinate. Upon exposure to light, these agents generate reactive oxygen species that induce cellular destruction. Some studies suggest that methyl aminolevulinate may be more effective than 5-aminolevulinic acid due to its greater lipophilicity.

Retinoids

Retinoids, derived from vitamin A, are used in conditions characterized by abnormal keratinocyte proliferation. Topical formulations are preferred over systemic retinoids due to the latter’s increased risk of side effects and teratogenicity. Relapse is common after discontinuation.[15](B3)

Cryotherapy and Other Surgical Dermatology Procedures

Cryotherapy, excision, curettage, and dermabrasion have demonstrated some effectiveness but are generally not used for extensive disease. Cryotherapy, in particular, often results in scarring, and recurrence is common.

Lasers

Several laser modalities, including carbon dioxide (CO2), Q-switched ruby (QSR), neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd:YAG), fractional photothermolysis, and Grenz ray, have been used in the treatment of DSAP. The carbon dioxide laser utilizes pulsed or scattered infrared light at wavelengths between 9.4 and 10.6 μm, targeting intracellular water to induce tissue vaporization. While effective, this approach may result in posttreatment hyperpigmentation. The Q-switched ruby laser selectively targets melanin, reducing hyperpigmentation without destroying the cornoid lamella, and offers deeper penetration than the Nd:YAG laser.

The Nd:YAG laser, operating at 532 nm, removes the superficial papillary dermis and has been shown to decrease hyperpigmentation while obliterating the cornoid lamella. Fractional photothermolysis creates small zones of thermal necrosis, minimizing damage, redness, and pain while promoting faster healing. Grenz ray therapy, which utilizes low-energy electromagnetic radiation similar to x-rays, inhibits cell proliferation by suppressing DNA synthesis.[16]

Immunosuppressive Agents

Medications that suppress the immune response, such as topical corticosteroids, are generally ineffective for DSAP, which is not an inflammatory disease. However, these agents may provide symptomatic relief for associated pruritus.[17][18][19][20][21](A1)

Topical Statin-Cholesterol

The combination of 2% simvastatin or lovastatin with 2% cholesterol cream has been shown to reduce lesion count, scaling, and erythema.[22][23] Since DSAP is often linked to mutations in the mevalonate pathway, which regulates cholesterol synthesis, supplementation with cholesterol and modulation of this pathway may help improve the condition or slow its progression.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of DSAP is broad and includes various papulosquamous conditions. Actinic keratosis is a primary consideration, distinguished by its centrally located scale, whereas the scale in DSAP is more peripheral. Actinic keratosis also occurs exclusively in sun-exposed areas, while DSAP may not be limited to these regions. Superficial BCC is another important differential, but it typically does not present with numerous lesions. Other conditions to consider include guttate psoriasis, other forms of psoriasis, granuloma annulare, lichen planus, seborrheic keratosis, tinea corporis, and flat warts.

Prognosis

Malignant transformation can occur in porokeratosis, leading to the development of SCC, SCC in situ, or BCC. Between 6.4% and 16.4% of porokeratosis lesions undergo malignant transformation, though the true rate may be closer to 6.9% to 11.6%. DSAP has been specifically reported to carry a 3.4% risk, though this rate may be underestimated.[24]

Complications

Complications of porokeratosis include symptomatic irritation and an increased risk of malignant transformation, with DSAP being one of the most frequently studied subtypes in this context.[25] Without treatment, progression may lead to malignancy.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be educated on monitoring lesions for recurrence and new development. Proper skin care for DSAP should be emphasized, including regular sunscreen use, adherence to sun safety measures, and compliance with treatment. However, individuals with genetic forms of the condition may not have a known history of sun exposure. These patients should conduct self-examinations and undergo regular skin evaluations to ensure timely assessment of lesions.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team is best suited to manage DSAP. Primary care providers should refer patients to dermatologists for confirmation of the diagnosis or specialized treatment. Oncologists and transplant physicians should maintain a high level of suspicion for DSAP, given its potential for malignant transformation. Clinicians should recognize DSAP as a premalignant condition and emphasize sun avoidance, including the risks of tanning spas. Any changes in lesion characteristics warrant a biopsy. Pharmacists play a key role in educating patients about medications, checking for drug-drug interactions, and ensuring adherence to treatment.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Cornoid Lamellae on Histopathology. This image shows multiple parakeratotic tiers (cornoid lamellae) overlying a vertical zone of dyskeratotic and vacuolated cells, findings consistent with porokeratosis. (hematoxylin and eosin stain, magnified 40x main and 100x inset).

Contributed by Mona Abdel-Halim Ibrahim, MD

References

Nova MP, Goldberg LJ, Mattison T, Halperin A. Porokeratosis arising in a burn scar. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1991 Aug:25(2 Pt 2):354-6 [PubMed PMID: 1894772]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShoimer I, Robertson LH, Storwick G, Haber RM. Eruptive disseminated porokeratosis: a new classification system. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2014 Aug:71(2):398-400. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.034. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25037793]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePopa LG, Gradinaru TC, Giurcaneanu C, Tudose I, Vivisenco CI, Beiu C. Disseminated Superficial Non-actinic Porokeratosis: A Consequence of Post-traumatic Immunosuppression. Cureus. 2024 Nov:16(11):e73218. doi: 10.7759/cureus.73218. Epub 2024 Nov 7 [PubMed PMID: 39650990]

Ebbelaar CF, Badeloe S, Schrader AMR, Plasmeijer EI. A large pruritic plaque in a patient with 2 kidney transplants. JAAD case reports. 2025 Mar:57():53-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2024.12.028. Epub 2025 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 39974501]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRomagnuolo M, Riva D, Alberti Violetti S, Di Benedetto A, Barberi F, Moltrasio C. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis following hydroxyurea treatment: A case report. The Australasian journal of dermatology. 2023 Feb:64(1):e72-e75. doi: 10.1111/ajd.13943. Epub 2022 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 36320094]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKang BY, Jacobsen J, Price HN, Andrews ID. Localized eruptive porokeratosis in pediatric patients following treatment of acute leukemia. Pediatric dermatology. 2021 Sep:38(5):1226-1232. doi: 10.1111/pde.14772. Epub 2021 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 34418147]

Herold M, Good AJ, Nielson CB, Longo MI. Use of Topical and Systemic Retinoids in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients: Update and Review of the Current Literature. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2019 Dec:45(12):1442-1449. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000002072. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31403546]

Wang X, Ouyang X, Zhang D, Zhu Y, Wu L, Xiao Z, Yu S, Li W, Li C. Two Novel and Three Recurrent Mutations in the Mevalonate Pathway Genes in Chinese Patients with Porokeratosis. Clinical, cosmetic and investigational dermatology. 2024:17():191-197. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S444985. Epub 2024 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 38283795]

Gu CY, Zhang CF, Chen LJ, Xiang LH, Zheng ZZ. Clinical analysis and etiology of porokeratosis. Experimental and therapeutic medicine. 2014 Sep:8(3):737-741 [PubMed PMID: 25120591]

Jin R, Luo X, Luan K, Liu L, Sun LD, Yang S, Zhang SQ, Zhang XJ. Disorder of the mevalonate pathway inhibits calcium-induced differentiation of keratinocytes. Molecular medicine reports. 2017 Oct:16(4):4811-4816. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.7128. Epub 2017 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 28765912]

Li X, Zhou Q, Zhu L, Zhao Z, Wang P, Zhang L, Zhang G, Wang X. [Analysis of clinical and genetic features of nine patients with disseminated superfacial actinic porokeratosis]. Zhonghua yi xue yi chuan xue za zhi = Zhonghua yixue yichuanxue zazhi = Chinese journal of medical genetics. 2017 Aug 10:34(4):481-485. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1003-9406.2017.04.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28777842]

Shirahatti T, Bangaru H, Sathish S. A Clinico-Epidemiological Study on Porokeratosis. Indian journal of dermatology. 2024 Jul-Aug:69(4):365. doi: 10.4103/ijd.ijd_131_24. Epub 2024 Aug 19 [PubMed PMID: 39296684]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNicola A, Magliano J. Dermoscopy of Disseminated Superficial Actinic Porokeratosis. Actas dermo-sifiliograficas. 2017 Jun:108(5):e33-e37. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2015.09.025. Epub 2016 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 27015657]

Pruitt LG, Hsia LL, Burke WA. Disseminated superficial porokeratosis involving the groin and genitalia in a 72-year-old immunocompetent man. JAAD case reports. 2015 Sep:1(5):277-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2015.06.011. Epub 2015 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 27051752]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSeverson KJ, Morken CM, Nelson SA, Mangold AR, Pittelkow MR, Swanson DL. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis treated with tretinoin and calcipotriene. JAAD case reports. 2024 Nov:53():105-108. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2024.08.040. Epub 2024 Sep 20 [PubMed PMID: 39493363]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRoss NA, Rosenbaum LE, Saedi N, Arndt KA, Dover JS. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis improved with fractional 1927-nm laser treatments. Journal of cosmetic and laser therapy : official publication of the European Society for Laser Dermatology. 2016:18(1):53-5. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2015.1063657. Epub 2016 Jan 28 [PubMed PMID: 26820042]

Weidner T, Illing T, Miguel D, Elsner P. Treatment of Porokeratosis: A Systematic Review. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2017 Aug:18(4):435-449. doi: 10.1007/s40257-017-0271-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28283894]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSkupsky H, Skupsky J, Goldenberg G. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: a treatment review. The Journal of dermatological treatment. 2012 Feb:23(1):52-6. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2010.495381. Epub 2010 Oct 22 [PubMed PMID: 20964569]

Kanitakis J. Porokeratoses: an update of clinical, aetiopathogenic and therapeutic features. European journal of dermatology : EJD. 2014 Sep-Oct:24(5):533-44. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2014.2402. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25115203]

Ramelyte E, Bylaite-Bucinskiene M, Dummer R, Imhof L. Successful Use of Grenz Rays for Disseminated Superficial Actinic Porokeratosis: Report of 8 Cases. Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland). 2017:233(2-3):217-222. doi: 10.1159/000478855. Epub 2017 Aug 18 [PubMed PMID: 28817832]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAird GA, Sitenga JL, Nguyen AH, Vaudreuil A, Huerter CJ. Light and laser treatment modalities for disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: a systematic review. Lasers in medical science. 2017 May:32(4):945-952. doi: 10.1007/s10103-017-2179-9. Epub 2017 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 28239750]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNguyen CM, Haller CN, Brichta L, Paller AS, Levy ML. Successful treatment of porokeratosis of Mibelli with pathogenesis-directed treatment of topical cholesterol-lovastatin. Pediatric dermatology. 2024 Nov-Dec:41(6):1253-1254. doi: 10.1111/pde.15657. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39563627]

Woźna J, Korecka K, Bowszyc-Dmochowska M, Jałowska M. Porokeratosis of Mibelli Treated With Topical 2% Lovastatin/2% Cholesterol Ointment. Cureus. 2024 Jul:16(7):e65871. doi: 10.7759/cureus.65871. Epub 2024 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 39219867]

Novice T, Nakamura M, Helfrich Y. The Malignancy Potential of Porokeratosis: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Cureus. 2021 Feb 2:13(2):e13083. doi: 10.7759/cureus.13083. Epub 2021 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 33680623]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceInci R, Zagoras T, Kantere D, Holmström P, Gillstedt M, Polesie S, Peltonen S. Porokeratosis is one of the most common genodermatoses and is associated with an increased risk of keratinocyte cancer and melanoma. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2023 Feb:37(2):420-427. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18587. Epub 2022 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 36152004]