Continuing Education Activity

Brain trauma or traumatic brain injury (TBI) results from a blow, bump, jolt, or penetrating injury to the head that disrupts the normal function of the brain. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of brain trauma and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology and epidemiology of brain trauma.

- Review the steps for an appropriate history, physical, and evaluation of brain trauma.

- Outline the treatment and management options available for brain trauma.

- Summarize interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance brain trauma and improve outcomes.

Introduction

Brain trauma or traumatic brain injury (TBI) results from a blow, bump, jolt, or penetrating injury to the head that disrupts the normal function of the brain. Symptoms vary greatly and may range from mild to severe depending on the degree of damage; imaging may or may not reveal changes. Patients with mild TBI may have transient changes in consciousness or mentation, while those with severe TBI may experience prolonged periods of unconsciousness, coma, or death. Factors that are often used to classify severity include changes in structural imaging, length of loss of consciousness, duration of altered mental status, post-traumatic amnesia, and GCS within the first 24 hours. Mild TBI is often called a concussion. Patients who have suffered any degree of TBI are at risk for long-term post-concussive symptoms, including changes in personality, emotional lability or depression, impairment in memory or ability to concentrate, or changes in sensation (visual or hearing changes). Patients who have experienced recurrent TBI are an area of active research, some of which have demonstrated that the cumulative effects of TBI put patients at risk for permanent damage.[1][2]

Etiology

Brain trauma may result from anything which may cause a blow, bump, jolt, or penetrating injury. Falls are the leading cause of TBI, accounting for 49% of TBI-related ED visits in children 0 to 17 and 81% of TBI-related ED visits in adults 65 years and older. Being struck by or against an object, motor vehicle collisions, and intentional self-harm are the most common causes of TBI. Among patients who require hospitalization for TBI, falls (52%) and motor vehicle collisions (20%) are the most common causes.[3]

Epidemiology

There are significantly more instances of brain trauma in males than females, with approximately 78.8% of injuries occurring in males and 21.2% in females. The most common cause of TBI is motor vehicle collisions, accounting for an estimated 50 to 70% of TBI accidents. In children and adolescents, about 21% result from sports and recreational activities. There are approximately 235,000 hospitalizations due to brain trauma. The cost estimates of direct and indirect costs of TBI are between $48 to 56 billion per year. The mortality rate is 30/100,000, approximately 50,000 deaths each year. About 50% of patients who do die, do so in the first few hours. The mortality starts rising around 30 years; it is highest in the elderly population, with falls contributing to a significant amount of brain trauma.[4][5]

Pathophysiology

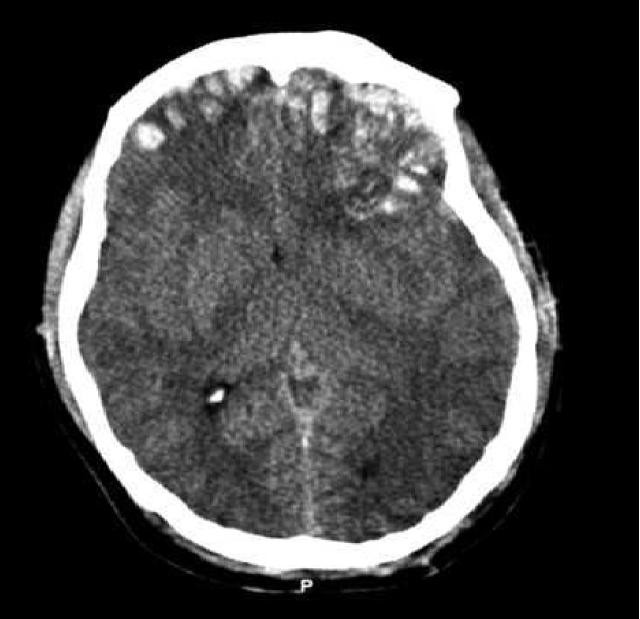

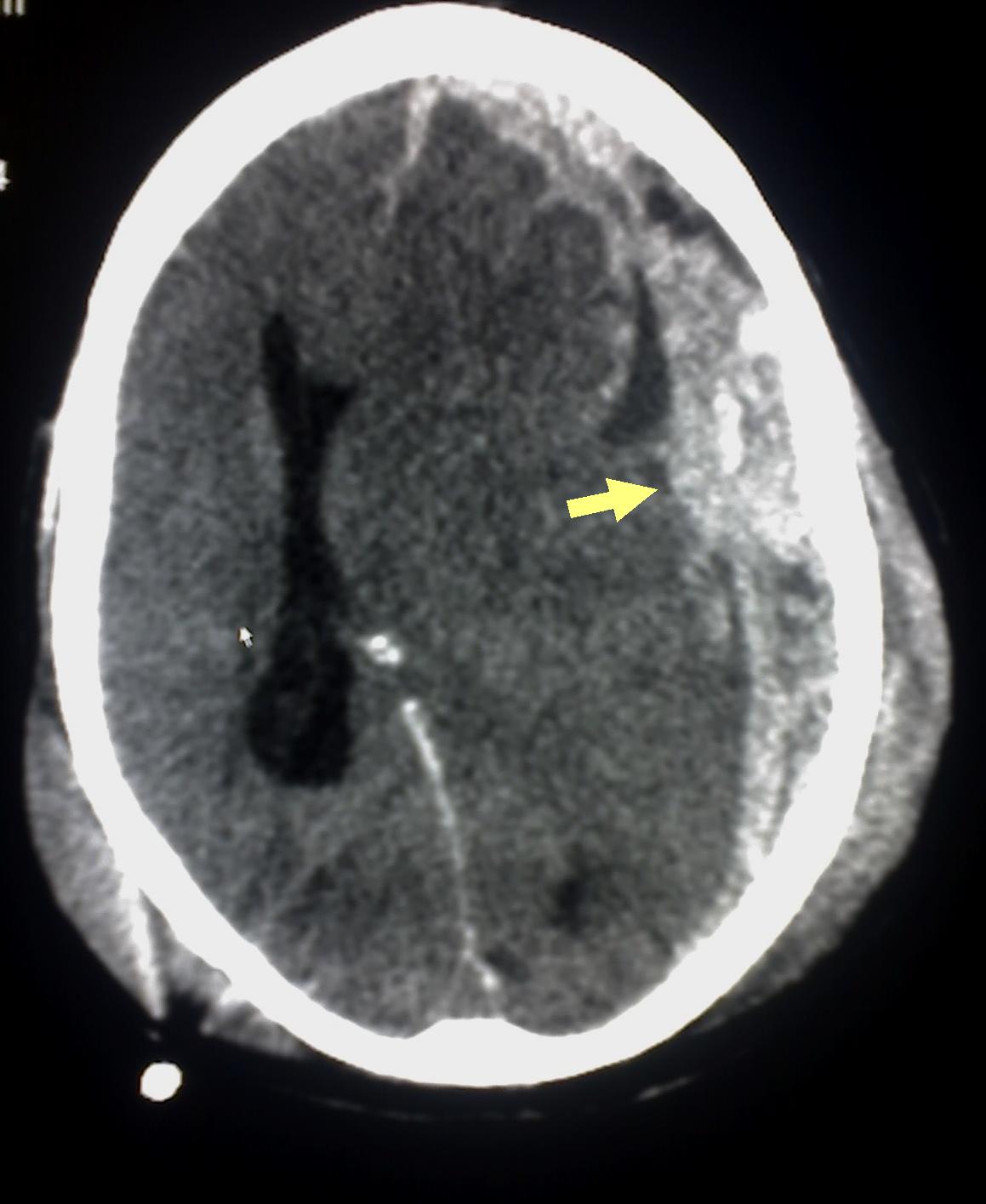

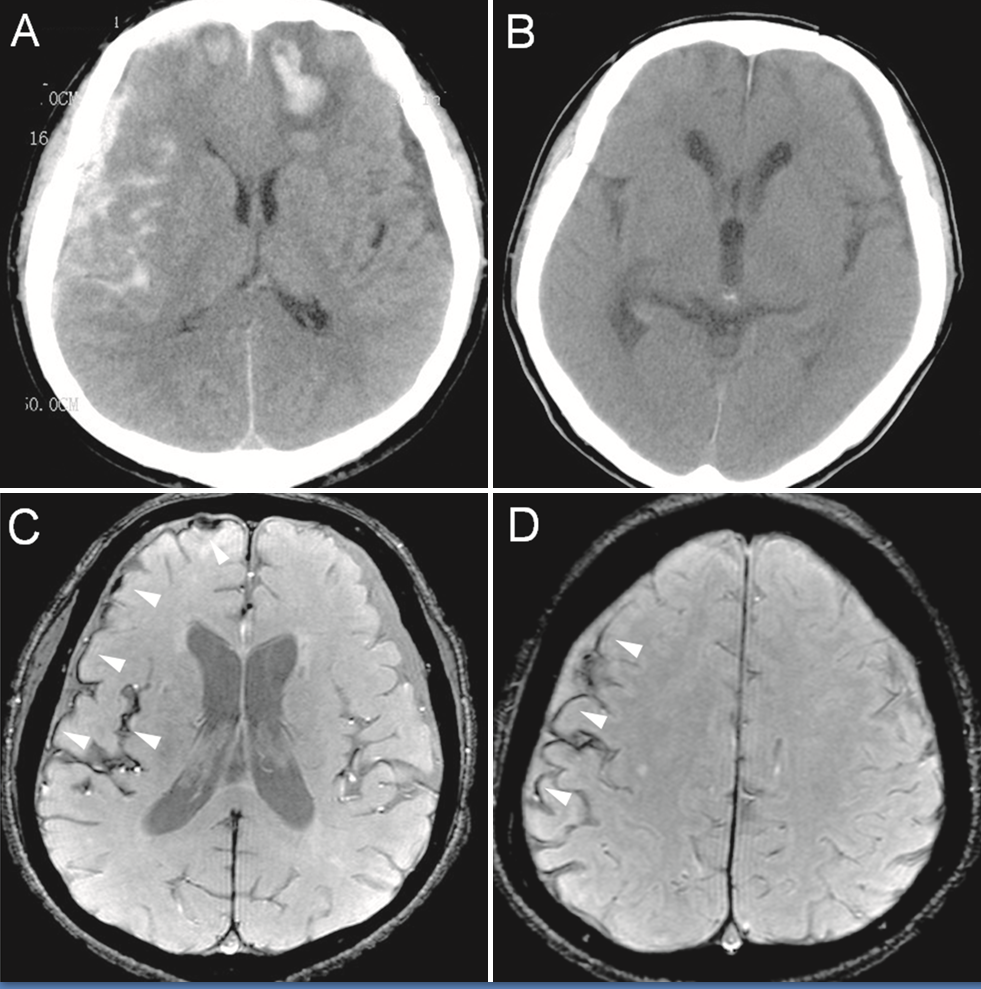

Brain trauma has both primary and secondary effects. Primary insult occurs due to the initial injury and may result in contusions, intracranial hemorrhage, and diffuse axonal injury. There may be no visible injury on imaging, and imaging is not always indicated to assess the primary injury. There are multiple types of traumatic intracranial hemorrhage, including epidural hematomas, subdural hematomas, intraparenchymal hemorrhage, intraventricular hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage. Diffuse axonal injury results from shearing forces and can cause neuronal axon stretching and tearing, leading to secondary damage. Diffuse axonal injury often impacts the junction between gray and white matter. There may also be coup-contrecoup injuries; coup injury occurs at the site of impact, whereas contrecoup injury occurs on the opposite side of the impact from rapid brain movement.

In the hours, days, and weeks that follow the primary injury, the initial damage triggers numerous secondary effects — secondary injury results from multiple factors. Calcium and sodium shifts, mitochondrial damage, and production of free radicals occurs, which may lead to the expansion of the initial injury. There is a release of presynaptic neurotransmitters such as glutamate, which activate NMDA receptors. This release leads to an influx of sodium and calcium and an efflux of potassium. The Na+-K+-ATPase pump attempts to re-establish balance and depletes ATP. TBI may also induce changes in the magnitude and duration of glucose metabolism, with a temporary increase in glucose uptake followed by glucose depression ipsilateral to the injury. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species may be increased in the period immediately following an injury. These changes may lead to damage to the axons, impairment of axonal function, and neuronal death. The secretion of cytokines may contribute to the development of vasogenic edema.[6][7][8][9]

History and Physical

History

The mechanism of injury and whether there was a loss of consciousness (and if so, for how long) are essential components in the initial evaluation. Symptoms may be non-specific and include nausea, vomiting, headaches, tinnitus, visual changes, dizziness, "foggy" feeling, or confusion. The clinician should determine the use of any antiplatelet or anti-coagulation agents. Focal neurologic deficits, including numbness, weakness, slurred speech, incontinence of bowel or bladder, altered mental status, or unconsciousness are red flags that necessitate brisk evaluation for intracranial hemorrhage, which is a neurosurgical emergency. In the longer term, many patients struggle with ongoing post-concussive symptoms, including dizziness, balance problems, cognitive difficulties, memory deficits, emotional lability, anxiety, depression, sleep difficulties, delusions, hallucinations, vision changes, and headaches.

Exam

Initial vitals are important to review. Cushing's triad, a combination of hypertension, bradycardia, and irregular or decreased respirations may present in patients with increased intracranial pressure.

Assuming that the patient's airway, breathing, and circulation are intact, the patient should then be evaluated using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), assessing for eye-opening, verbal responses, and motor responses. The minimum score is 3, and the maximum score is 15.

Glasgow Coma Scale[10]:

Eye-opening response

- Spontaneous (4)

- To verbal stimuli (3)

- To pain (2)

- No response (1)

Verbal response

- Oriented (5)

- Confused (4)

- Inappropriate words (3)

- Incomprehensible speech (2)

- No response (1)

Motor response

- Obeys commands for movement (6)

- Purpose movement to painful stimuli (5)

- Withdraws to painful stimuli (4)

- Flexion response to painful stimuli (decorticate posturing) (3)

- Extension response to painful stimuli (decerebrate posturing) (2)

- No response (1)

Battle sign (bruising behind the ears), raccoon eyes (bruising beneath the eyes)[11], hemotympanum, and CSF otorrhea or rhinorrhea are signs of basilar skull fracture and highly associated with intracranial hemorrhage. Pupil response is testable in all patients. A fixed, dilated pupil ("blown" pupil) on one side may correspond to ipsilateral hemorrhage and herniation.

A thorough neurologic exam, including assessment of cranial nerves, strength, sensation, reflexes, and clonus, should follow in patients who can cooperate with the exam. Gait testing should be performed in patients not suspected of cervical spine injury, though most patients with a severe head injury will require cervical spine immobilization until ruling cervical injury out clinically and radiologically. In patients who are following up after brain trauma, further neuropsychiatric testing may be necessary.

Evaluation

The Evaluation of Patients with Suspected Brain Trauma

Laboratory studies may be considered, including CBC, CMP, coagulation profile, type and screen, and ABG. Whether to obtain or what laboratory studies are of value may depend on the severity of the injury or associated polytrauma.

The initial imaging study of choice is the head CT, as it is often readily available and rapidly obtainable. Head X-rays are not recommended due to inferior usefulness, and CT studies are available in most centers. MRI can be of utility but takes much longer to obtain than head CT. It may be indicated in follow up for head injuries, but is not used as the initial evaluation.

Clinical Decision Rules

Several clinical decision rules apply to the initial evaluation of head trauma. These rules essentially allow the provider to stratify, in which patients require CT imaging to evaluate their head trauma further.

Perhaps the most widely known and best-studied rule is the Canadian head CT rule. The Canadian head CT rule has inclusion and exclusion criteria. Patients to whom this rule applies are those with GCS 13 to 15 with loss of consciousness, amnesia to the head injury event, or witnessed disorientation. Patients who are less than 16 years old, are on blood-thinning medications or have a seizure after the injury are excluded from this decision rule. The Canadian head CT rule puts forth the following high-risk criteria: GCS less than 15 at 2 hours post-injury, suspected open or depressed skull fracture, any signs of basilar skull fracture (hemotympanum, raccoon eyes, Battle sign, CSF otorrhea or rhinorrhea, two or more episodes of emesis, and age 65 years or older. Medium risk criteria include retrograde amnesia to the event of 30 minutes or greater, or a dangerous mechanism (pedestrian struck by motor vehicle, occupant ejected from a motor vehicle, or fall from over 3 feet or more than five stairs). If the patient is a candidate for the application of the rule and has no high or medium risk criteria, CT is not a recommendation. The sensitivity of this rule is 83 to 100% for all traumatic intracranial findings and 100% for findings requiring neurosurgical intervention. If either of the medium-risk criteria is positive, CT merits consideration, and if any of the high-risk criteria are positive, the decision rule cannot rule out the need for imaging.

Other decision rules to determine whether initial head CT is a recommendation include New Orleans Rule and Nexus II Rule.

The New Orleans Rule has more stringent inclusion criteria, requiring age greater than 18 and GCS of 15 in patients with blunt head trauma occurring within 24 hours, causing loss of consciousness, amnesia, or disorientation. These rules recommend head CT in any patients with headache, vomiting, age greater than 60, drug or alcohol intoxication, persistent anterograde amnesia, visible trauma above the clavicles, or seizures.

Nexus II Rule recommends CT in any of the following: patients greater 65 years or older, evidence of skull fracture, scalp hematoma, neurologic deficit, altered level of alertness, abnormal behavior, coagulopathy, recurrent or forceful vomiting.

In pediatric patients, the best decision tool to determine the recommendation of the CT scan is PECARN, which is based on a large-scale clinical trial of the same name and has had repeated external validation. This decision tool divides patients into two initial groups based on age. Those less than two years old are further stratified using one algorithm, and those 2 years old or older are further stratified using another algorithm. Children less than 2 years old who have GCS less than 15, altered mental status, or a palpable of a skull fracture should undergo CT. If a child less than 2 has a loss of consciousness longer than 5 seconds, non-frontal hematoma, severe mechanism of injury, or not acting normally per parents should undergo CT or observation; this decision should be made using shared decision making with parents. If not meeting any of the criteria mentioned above, the clinician may safely discharge the child. In children 2 years or older, AMS, GCS less than 15, or signs of basilar skull fracture should precipitate CT imaging. Children 2 years or older who have a loss of consciousness for longer than 5 seconds, recurrent vomiting, severe headache, or high mechanism of injury should either be observed or undergo CT imaging. If the child presents none of these symptoms, the clinician may safely discharge the child.[12]

Rancho Los Amigos Scale

This scale is used to describe the behaviors, cognitions, and emotional responses in patients who are emerging from a coma.

- Level I: No Response: Total Assistance - no response to stimuli

- Level II: Generalized Response: Total Assistance - inconsistent and non-purposeful responses

- Level III: Localized Response: Total Assistance - inconsistent response

- Level IV: Confused/Agitated: Maximal Assistance - bizarre, non-purposeful behavior, agitation

- Level V: Confused, Inappropriate Non-Agitated: Maximal Assistance - response to simple commands, non-purposeful, and random response to complex commands.

- Level VI: Confused, Appropriate: Moderate Assistance - follows simple commands, able to understand familiar tasks, but not new tasks

- Level VII: Automatic, Appropriate: Minimal Assistance for Daily Living Skills - Able to perform daily routine and understands familiar settings. Aware of diagnosis, but not impairments.

- Level VIII: Purposeful, Appropriate: Stand By Assistance - Consistently oriented to person, place and time, and some awareness of impairments and how to compensate. They can carry out familiar tasks independently but might be depressed, and/or irritable

- Level IX: Purposeful, Appropriate: Stand By Assistance on Request - Able to complete different tasks, aware of impairments, able to think about consequences with assistance

- Level X: Purposeful, Appropriate: Modified Independent - Able to multitask in many different environments. May create tools for memory retention and anticipate obstacles which may result from impairments[13]

Treatment / Management

Treatment depends on the severity of brain trauma.

If no hemorrhage is present on CT or the patient meets criteria that do not indicate CT is necessary:

If the patient has a GCS of 15 and no focal neurologic deficits, the patient has a mild TBI and may be safely discharged. Post-concussive symptoms are possible, and the clinician should discuss these with the patient. As previously discussed, some symptoms include headaches, mood changes, difficulty concentrating, or nausea. The patient may exhibit no symptoms and have a full recovery, or they may have symptoms that last for days to weeks. Some patients, in particular, those with a history of recurrent TBIs, may exhibit life-long symptoms. The patient should be cautioned to return for persistent nausea or vomiting, changes in mental status, seizures, weakness, numbness, severe headache, drainage from the ears or nose, or visual changes. If the patient had GCS of less than 15 or has any concerning exam findings, the patient may require further evaluation. Remember, it is possible to have medical reasons, including ischemic stroke, carotid or aortic dissection, or metabolic etiologies, which can lead to accidental traumatic injuries. The patient may require further laboratory studies or imaging. CT angiography or MRI merit consideration if a non-contrast CT is non-diagnostic

If hemorrhage is present on CT:

Airway

- Maintain SpO2 of at least 92%

- In patients with GCS under 8, intubation should merit strong consideration, as it is unlikely that they will be able to maintain their airway.

Intubation:

- Patients should be pre-oxygenated as the risk of hypoxia outweighs the risk of hyperoxia.

- Historically lidocaine has been used for pre-treatment to blunt sympathetic response to airway manipulation during laryngoscopy, but studies have shown no definitive benefit.

- Etomidate allows hemodynamic stability and is a commonly used first-line agent for induction, though it has a reported risk of adrenal insufficiency. Propofol may be useful in lowering blood pressure, and thus the intracranial pressure in hypertensive patients. It may also have anti-epileptic effects. Ketamine has a theoretical risk of increasing intracranial pressure, though more recent studies have been mixed on this. It may be useful in hypotensive patients to increase MAP and CPP.

- Paralytic agents such as rocuronium, vecuronium, or succinylcholine may be a consideration, however, these agents will limit the ability to perform a neurologic exam after administration.

Breathing

- Hyperventilation is somewhat controversial. It may be transiently helpful in patients with increased intracranial pressure as hypocapnia may induce cerebral vasoconstriction and transiently decrease the expansion of hemorrhage; however, this is a temporizing measure to definitive management. Prolonged hypocapnia may cause cerebral ischemia. Targeting low-normal pCO2 of approximately 35 is reasonable. [14]

Circulation

- Maintain normotension with target SBP greater than 90 and less than 140

- Initiate fluid resuscitation with normal saline with the goal of euvolemia.

- If the patient has hypotension that is refractory to fluid resuscitation, vasopressor support should be initiated. Phenylephrine may be the best choice for a neurogenic shock as it has pure vasoconstriction effects, and studies have shown that it increases cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) without increasing intracranial pressure (ICP). In patients who are bradycardic due to Cushing's reflex, norepinephrine may be a better choice.

- Packed red blood cells should be transfused for a goal of Hb over 10 mg/dL in severe TBI.

- Coagulopathy should be corrected.

Increased intracranial pressure

- Cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) = mean arterial pressure (MAP) - intracranial pressure (ICP)

- Elevation of the head of the bed to 30 degrees or reverse Trendelenburg positioning can lower ICP

- Hyperosmolar therapy via mannitol using a bolus of 1 g/kg and/or hypertonic saline (dosing depends on the concentration available and vascular access) may be given to reduce ICP

Seizures

- Patients with severe TBI, including GCS less than 10, cortical contusion, depressed skull fractures, subdural, epidural, subarachnoid, or intracerebral hemorrhage, penetrating head injury are at risk for seizures.

- Seizure activity that is apparent clinically or on EEG should receive management with benzodiazepines and anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs).

- Propofol may be optimal for post-intubation sedation.

- AED prophylaxis should also is a viable option in severe TBI patients. Phenytoin or fosphenytoin are first-line, levetiracetam is an alternative that may have fewer side effects. Prophylaxis should last for 7 days.

Neurosurgery consultation is necessary for patients with intracranial hemorrhage. While some patients may be monitored clinically and have repeat imaging studies to visualize if there is expansion, definitive management may be required. A Burr hole may be an option to evacuate a hematoma in an emergent setting with herniation. Patients may require a decompressive craniectomy. Patients may require close monitoring of intracranial pressure via an extraventricular drain (goal 10 to 15).[15]

A multi-factorial approach is crucial to the long-term management of patients who have experienced brain trauma.

Rehabilitation

Many patients who have experienced brain trauma benefit from early initiation of rehabilitation services. Physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy should all be options. After the initial stabilization, patients may benefit from care in an acute rehabilitation service or hospital, which allows the patient to undergo more intensive therapy. Patients will often need to continue treatment as an outpatient and may require new assistive devices or modifications to their homes or vehicles. Goal-directed therapy focuses on maximizing functional capacity is pursued during rehabilitation.

Psychological impacts

In addition to cognitive dysfunction and residual neurologic deficits, patients who have experienced brain trauma have increased rates of psychological disorders, including mood disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, and schizophrenia. Psychotherapy or medications directed toward treating comorbid disorders can improve mental health and decrease the risk of suicide. Patients also benefit from having a network of support in their close friends and family as well as in the community as a whole. Case management or social workers can assist in providing outpatient resources in the community.[15][16]

Differential Diagnosis

If there is a known injury, the differential includes concussion, intracranial hemorrhage, and diffuse axonal injury. Classically, an epidural hematoma occurs from the tearing of the middle meningeal artery and results in a convex-shaped hematoma between the skull and dura mater; the blood does not cross the suture lines. A subdural hematoma classically occurs due to the rupture of the bridging veins and results in a crescent-shaped hemorrhage between the dura mater and the arachnoid mater. There may also be intraparenchymal hemorrhage or intraventricular hemorrhage. In contrast to subarachnoid hemorrhage due to aneurysm rupture in which blood tends to collect around the circle of Willis, traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage typically occurs near skull fractures.

Polytrauma is also possible in patients with brain trauma and indicates a head-to-toe evaluation. Brain trauma may be associated with spinal fractures, chest or abdominal blunt or penetrating trauma or trauma to the extremities.

If there is no known injury, but a patient presents with altered mental status or neurologic deficits, brain trauma is a consideration on the differential diagnoses. Many other etiologies may cause neurologic dysfunction, including metabolic encephalopathy, ischemic stroke, carotid or aortic dissection, meningitis, encephalitis, seizure activity, or postictal state, brain mass, multiple sclerosis.

Prognosis

Prognosis is highly variable in patients who have experienced brain trauma, but there are factors used to predict prognosis early in the course. Depth and duration of coma, post-traumatic amnesia, age, results of imaging studies (particularly CT), and intracranial pressure all contribute to the estimated prognosis. However, individual patients may always have better or worse outcomes depending on co-morbidities and unknown contributing factors. Low GCS, age greater than 60 or less than 2, and longer post-traumatic amnesia are all associated with worse outcomes.

Some patients will recover well and regain full functionality after brain trauma, particularly those who have experienced a mild traumatic brain injury. Patients who have suffered a more severe traumatic brain injury may go on to have life-long deficits and significant disability. The most critical patients may die or persist in a vegetative state.[17]

Complications

Brain trauma has acute and longitudinal impacts.

In the acute setting, brain trauma commonly correlates with polytrauma, and there may be dysfunction or failure of other organs. Patients may experience cognitive impairment, sensory processing impairment, which may result in a comatose state in severe brain trauma. Patients may have cerebrospinal fluid leakage and vascular or neuronal injuries. Seizures may present immediately or further down the line. There may be a transient or persistent increase in intracranial pressure due to acute hemorrhage or vasogenic edema, which can result in herniation. Brain death is the most severe consequence.

Many factors contribute to neuropsychiatric sequelae, and the post-concussive syndrome is common. Factors that contribute include a history of neurologic disorders, psychiatric diagnoses, substance abuse, poor social support, and the severity of the inciting injury. Post-concussive syndrome may consist of difficulty sleeping, difficulty concentrating, irritability, fatigue, memory problems, headaches, difficulty thinking, dizziness, vision changes, and light sensitivities. Psychiatric disorders for which patients are at increased risk include depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, and panic disorder. Patients may be at increased risk of substance abuse. Many cognitive difficulties may ensue as a result of brain trauma, particularly executive function impairment. Patients may experience irritability, aggressive behavior, and agitation. Problems with short-term memory and processing are not uncommon. Patients who have suffered traumatic brain injuries may also experience sleep dysfunction, which is often due to sleep-disordered breathing.[18]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Prevention is critical to brain trauma. Motor vehicle collisions, the most common cause of brain trauma, are not always preventable. However, some measures can be done to decrease risk, including wearing a seatbelt, not driving under the influence of drugs or alcohol, and using appropriate booster seats for children based on age. Bicyclists and motorcyclists should be encouraged to wear a helmet. There is active research on recurrent traumatic brain injuries in sports. In a patient who has already experienced brain trauma, it is important to not return to activities until he or she has improved. Recurrent brain trauma may put patients at risk of lifelong symptoms, and there may be cumulative and permanent effects.

In patients who have already experienced an injury, post-trauma recovery is a challenging process of physical, mental, and emotional recovery. Neurologic and psychiatric complications are common. Suicide prevention in patients who have experienced brain trauma is also important, and patients should always be encouraged to seek help.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team is crucial to successful treatment and rehabilitation of patients who have experienced brain trauma. A case manager or social worker can assist in providing information regarding resources, coordinating appointments, assisting with discharge planning, and working with insurance so that the patient may receive the care they need. Occupational therapists help in improving functional status and focus on activities of daily living, which may suffer severe limitations due to traumatic brain injuries; they may recommend alterations to the home to improve functional capacity. Physical therapists may recover strength, endurance, and coordination; they may also recommend the use of assistive devices and provide training on how to use them. Speech-language pathologists may evaluate and treat communication and swallowing difficulties. The nursing staff is vital at every stage, from providing intensive monitoring and potentially total care in an acute setting to educating patients in the longer term. A physiatrist may oversee the rehabilitation team and determine if a patient is appropriate for intensive rehabilitation programs. A primary care provider is key in long-term follow-up and coordinating care in patients with brain trauma. A neurologist is a physician who diagnoses and treats conditions of the nervous system, which include brain trauma and post-concussive syndrome. A neurosurgeon is a physician who determines the need for surgical intervention and performs such interventions as indicated. A neuropsychologist can perform more extensive cognitive testing and aid in assessing the patient's ability to manage their financial, legal, and medical decisions. If any pharmaceutical therapy plays a role in management, a pharmacist must be on the case to evaluate dosing, drug interactions, and counsel regarding adverse effect potential.

A coordinated interprofessional team effort is absolutely essential in the diagnosis and management of brain trauma injuries, and only through this approach can patient outcomes achieve their optimal results. [Level V]